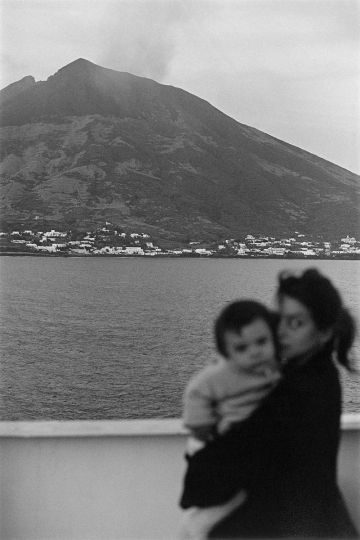

At 17, I wanted to travel around the world and fight with reality. Later, as a student of architecture, during the university holidays, while my friends were sunbathing on the beaches, I preferred to go to the field, with the conviction, already, that the images could change the course of history, offer a heroic and humanistic look at events. I imagined myself a reporter, like a Nick Ut or a Larry Burrows. In 1975, when I was 23 years old, I headed for Lebanon, which was sinking into civil war, then that of Angola, which has been in turmoil since independence in 1976.

In 1978, feeling the beginnings of an upheaval in Iran, I decided to go there. This was the first of my innumerable trips to Persian land. Iran was then led by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The Pahlavi dynasty had ruled the country since 1925. But at the end of the 1970s, faced with glaring inequalities, the people, led by the left parties and especially the Shiite clergy, began to make their voices heard. He aspired to more social justice and also wanted to take advantage of the huge revenue from oil. Faced with this growl, Pahlavi, through his powerful political police, the Savak, and supported by his unwavering American ally, violently repressed the opposition. When, at the beginning of 1978, the press began to evoke disturbances in the region, I spoke of a possible revolution in Iran to Goksin Sipahioglu, head of the Sipa agency. His answer was ironic: “You do not think about it! Do you know who the shah is? Every week, the world press publishes reports to the glory of the imperial family. How can you imagine that a regime with such a powerful and America-supported army could collapse because of some poor turbaned religious? I decided to go there anyway. I arrived at Tehran by night and disembarked in a shabby hotel near the bazaar, which I knew to have been there before. I had little money and I was alone. I did not know anyone and I did not speak Persian … I spent several weeks wandering the streets of the capital, looking in vain for these events that spoke about the press. It was a failure, I returned empty-handed to Paris.

Nevertheless, I was certain that the story was just beginning. A few weeks later, I left. I made the choice to work on the imperial family, following the unstoppable argument of the director of the agency Sipa: “You know, it will be significantly more profitable than your stories of mullahs lousy. Once again, he was right. A few weeks later, my reports on the shah were published in the press. These first stays, certainly not glorious, allowed me to earn my living, but especially to acquire a more intimate knowledge of the country, to make contacts, which would serve me later to cover as a photographer and privileged witness these events if of the revolt of the mosques in 1978, while the shah’s regime still seemed indestructible, until the victory of the “prophet” in 1979.

As a photographer, it was immediately very easy for me to merge with the Iranian people. On the one hand because I have always been mistaken for an Iranian. On the other hand, because Iran is, par excellence, the “land of images”. This interest for the image, paradoxical in an Islamic country where photography is often badly tolerated or forbidden, as in Taliban Afghanistan, is very old in Iran and related to Shiism. It is found on the Isfahan miniatures, but also in the cemeteries, where the tombs are decorated with very realistic photos of the deceased. Wall paintings are ubiquitous in the streets and Iranian filmmakers are awarded worldwide.

About the book

This book is above all a visual testimony. I wish to tell what I saw and lived day by day, to be a simple “reporter of history” … which would not bring any judgment on history.

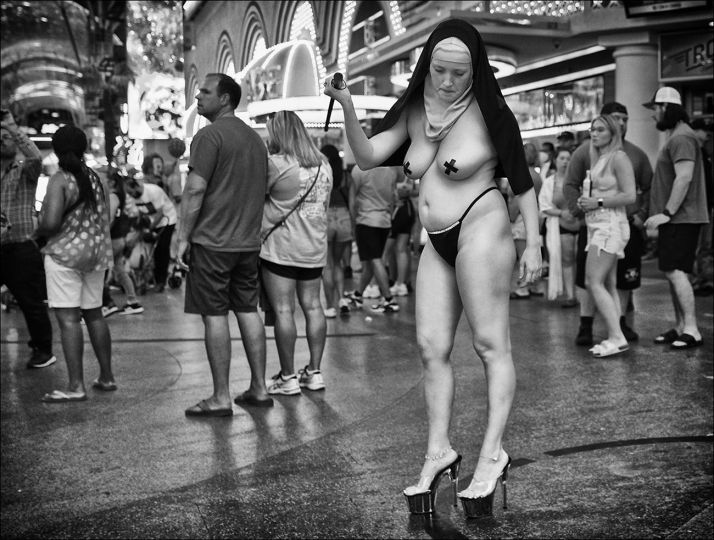

For several years, I worked mainly on black and white books. I retouched my images with restraint, respecting the codes of monochrome classical photography. By avoiding, if possible, strident, saturation and false notes …

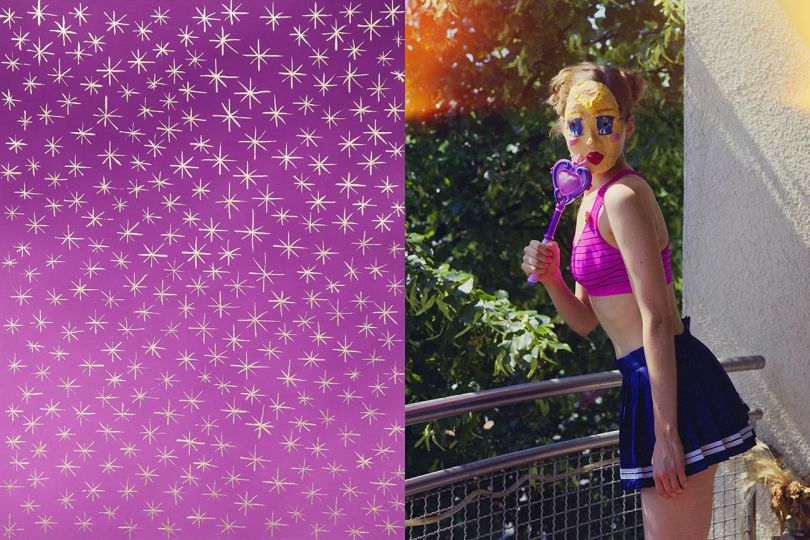

But over the years, an idea has emerged. I wanted to show images out of the ordinary, to go further, to switch to another visual universe. I then began to push the sliders of my computer programs, to tell my stories differently. A schizophrenic work on two fronts, as if I listened in stereo to classical music and rap …

My images of the revolution lent themselves, as if by magic, to all these manipulations, more and more graphic and refined. Curiously, my original black and white photographs were in fact made of gray, half-tones: pushing the sliders a bit further, I made the lines appear, black and white, nothing more … The pictures became drawings in the line, like calligraphy. My work turned into a kind of “photo-graphic” comic.

Unlike painting, photography claims to represent reality. A feeling of guilt tapped the former photojournalist that I am.

For a reporter of reality, transforming images is the crime of lese-photography. Photographers excommunicated by their peers, as a result of retouching too visible, are not lacking, as evidenced by the controversy around Steeve McCurry, who defended himself by defining his work as a “visual narration”. Over forty years of practice have convinced me that photography is just a pretense. It is a representation of reality among others, an art consumed by subterfuge, even lies, which persists in making us believe in its truth, a wonderful illusion, telling the person who plunges its own history, receptacle of his “image-inary” …

For this book, I decided to emancipate myself from the rules induced by photography and to stop pretending to reality. I wanted to get out of the world of photography to penetrate into that of the image, two visual worlds with porous borders … A little like the “old masters”, I have contrived contrasts, filters, lights, colors and lines with

innovative computer tools … Like a musician who would pass from the piano to the synthesizer. My project plays on the stresses and the saturation, the lines and the curves, the true and the false, the blur and the net. But these transfigured images remain photography, demanding a good initial quality. Unlike drawing, their capture is provided by a photographic tool, which always respects the laws of geometric perspective (optika, in Greek).

The result surprises, baffles sometimes. Difficult to define the lines between the world of photography and that of the image. Pushing these limits has opened up new opportunities for storytelling in pictures. I searched for a long name for this OPNI (unidentified photographic object). It was enough to add a hyphen between photo and graphic to reconnect the links between photo and image …