Written by Luc Debraine

The Swiss photographer spent four months in residence in Budapest last year. Before organizing an outdoor exhibition last spring, which garnered criticisms and praises.

In the 1980s, Michael von Graffenried was the enfant terrible of Swiss photography. He had surprised, among other insolences, the parliamentarians of the Federal Palace dozing off or with their fingers in their noses. Scandal! The photographers accredited to the Palace had tried to deny entry to their young colleague, even though he is from one of the oldest and illustrious Bernese families.

Four decades later, Michael von Graffenried has not changed. He remains faithful to his credo of showing what power or propriety cannot bear to look at. He forced the Swiss to look at their drug scene by plastering his images in train stations across the country. He was one of the few photographers present in Algeria during the black decade. Its outdoor exhibition in the holy city of Benares, India, was censored after two days. The authorities and the press of New Bern in North Carolina, founded in 1710 by an ancestor of Michael von Graffenried, do not want to hear about the book that the photographer devoted to the small southern town (Editions Steidl, 2021). And so on, from the popular streets of Cairo to the Oktoberfest in Munich, from Sudan at war to Rio de Janeiro in full preparation for the Olympic Games.

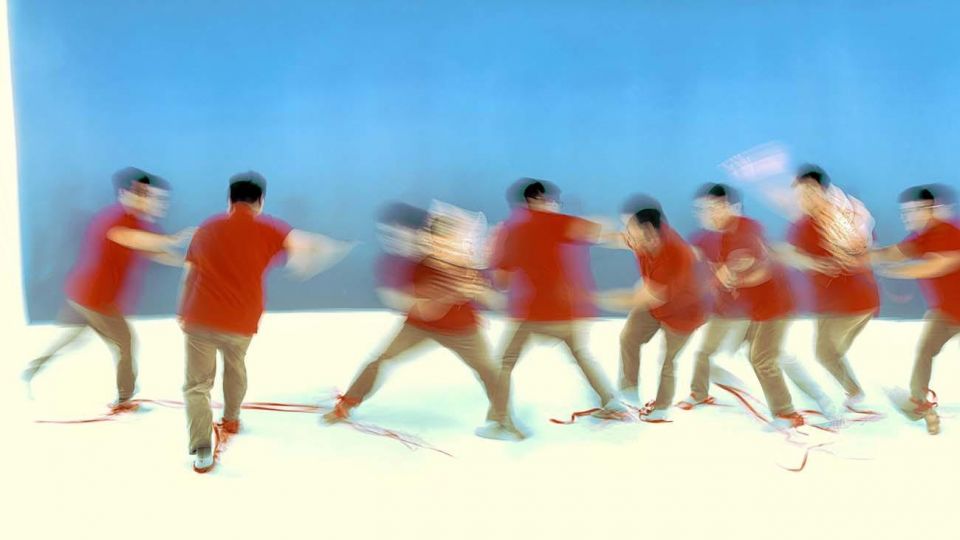

However, the person concerned does not lay claim to the word “provocation”. “I prefer the idea that reportage photography should trigger a small electric shock. This shock has no other raison d’être than to encourage reflection, especially to question one’s own preconceptions,” he says. This tense gaze has passed, for thirty years, through a controlled use of the panoramic format. Framing allows you to include as much information as possible in the image. It goes beyond description to create a narrative, so much so that Michael von Graffenried almost never captions his photographs.

The Hungarians who discovered Michael von Graffenried’s latest reportage last spring did not actually need an explanation to grasp its content. With the benefit of a scholarship from the Swiss foundation Landys+Gyr, the photographer spent the last four months of 2021 in Budapest. He was interested in religious ceremonies, nationalist holidays, shooting ranges, supporters of President Viktor Orban, the homeless, the oligarchs on the prowl on Lake Balaton, the neo-Nazis, the Roma, the evening cocktail-parties in short, everything that the propaganda of a country with an authoritarian tendency avoids like the plague.

Thanks to the support of the center-left Budapest City Hall and the Pro Helvetia Foundation, Michael von Graffenried was able to exhibit twenty-six large photographs in the central Deak Ferenc square last May. The outdoor exhibition was held as part of the Spring Festival. Many passers-by appreciated this sharp look at the contemporary Hungarian society. Others less. Letters of protest soon arrived at the town hall. The mother of a young neo-Nazi, photographed with a swastika on her arm in front of a metro station, refused any dialogue with Michael von Graffenried. It was discovered that this mother belonged to the circles close to the presidential power. The photographer ended up replacing his image with a scene of a synagogue in Budapest. The boss of a club for transvestites complained that the photographer had not asked him for permission, even though the club is very present on social networks. Michael von Graffenried covered his photo with the wide shot of a mass held in honor of Pope Francis’ visit to Budapest in September 2021.

Despite these two censorships, and some additional graffiti, the exhibition “Magyarok – The Hungarians” completed its term last May. To the great satisfaction of the photographer, always sure of the opening date of his public events, a little less of their closing date.

Luc Debraine