His name : Michael Friedel. He is one of the greatest German photographers, but especially from the end of the 1960s : he is the photographic discoverer of the Seychelles and especially of the Maldives. We dedicate this day to him.

Poetry of the Early Years

The Work of the Photographer Michael Friedel

by Hans-Michael Koetzle

It could be said that Michael Friedel has lived three lives as a photographer. That may not seem much when compared with The House with Fifteen Keys, in which the Paris-based photographer Frank Horvat looks back on his multi-faceted work. But, all in all, it is enough to catch the critics off guard. A man who regularly strikes out on new paths in pictorial language and choice of subject-matter, who suddenly pivots in composition and aesthetic, focusing without warning on different objects; constantly reinventing himself against the backdrop of a changing world – Friedel is someone whose work is indefinable in the eyes of a profession that likes recognizable labels. Pigeon-holes are preferable to surprises.

Michael Friedel’s approach to photography has a lot to do with the changes within our increasingly globalised culture. But he also shows an uncompromising desire for freedom, the wish to break out and break away time and again, to discover what is photographically new. He would not have felt happy caged in a publishing-house or news-room, or even a photographers’ cooperative, but neither did he, or does he, want to become known only for certain themes, or be subject to the strictures of a particular style of image. All his life Friedel has been, in the best sense of the word, a flâneur, a gifted eclectic, strolling through the heterogeneous terrain of a medium that can be anything he wants: monochrome or colour, deeply engaged or spontaneous, meditative or overwhelming, quiet or surprising, informative, light-hearted, epic, obsessed with detail…

Michael Friedel was born in Berlin in 1935, and after spells in Munich and Hamburg, he has made his home in the small town of Dietramszell, in Upper Bavaria. His status as the least famous celebrity of his generation is due to his modesty, lack of vanity and a rather unassuming manner – and to the fact that, over the past six decades, he has spent more time in distant corners of the world than he has on curating his life’s work. To date, there has been no big retrospective exhibition of his work – which is astonishing in view of a career that had a brilliant start in the 1950s. Michael Friedel was in fact considered one of the best in his generation. As the critic Bernd Lohse wrote as early as 1954, while others “tentatively groped their way”, Friedel “ captured scenes from everyday life in Italy with a sure hand, clarity of composition and often an amusingly observant eye.” Travelling and photography; taking pictures and getting them published – this became nothing less than a vocation for Michael Friedel, rapidly confirmed by publication in practically all the big illustrated magazines of those years. In 1954, when he was still only 19, he had his first lead photo in Stern, and in 1956, with his portrait of the young Elvis Presley, an unmissable front-cover of Der Spiegel. In both 1954 and 1956 he won the Young Photographer of the Year award at the Photokina exhibition.

This encouraged the amateur Michael Friedel and brought him to the notice of a camera-keen public. In 1960 Karl Pawek included a Friedel picture in his much-discussed book Totale Photographie, thus ensuring appearances for the newcomer in all four World Exhibitions of Photography – 1964, 1968, 1973 and 1977.

Regularly between 1955 and 1978, Michael Friedel’s latest work was presented in Das Deutsche Lichtbild , the annual review of German photography, published by Wolf Strache.

His pictures could also be seen in magnum, the influential ‘journal of modern life’, published by Dumont, as well as in twen, the trendy life-style magazine designed by Willy Fleckhaus, where his work was printed alongside such big names as William Klein, Bruce Davidson and Irving Penn. At that point Friedel could have established himself in the field of monochrome camera art with an emphasis on aesthetic composition. Yet ultimately he saw himself, and still does, as a photo-journalist. As he puts it, he wants “to present current events to the public with impact and immediacy, while letting the image make my own standpoint very clear.”

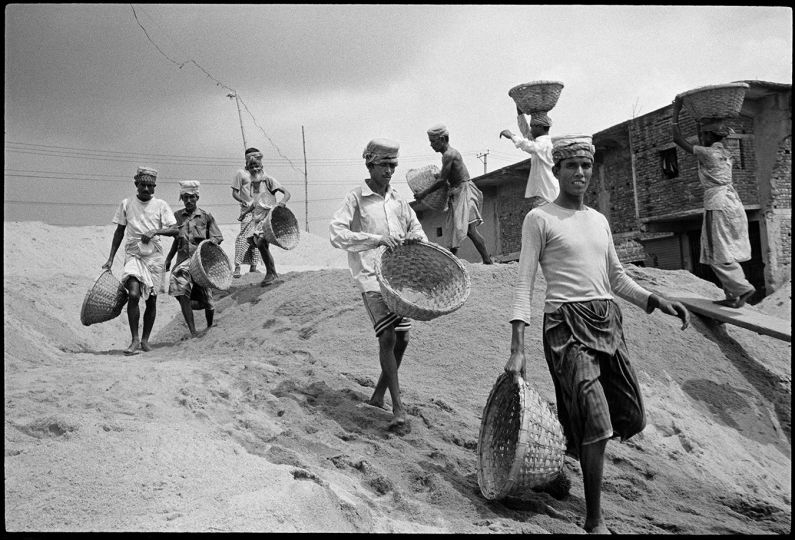

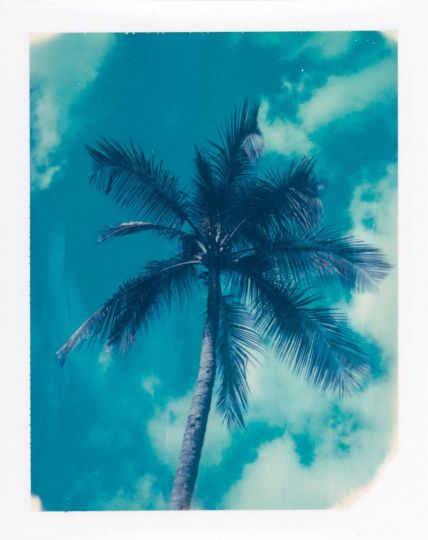

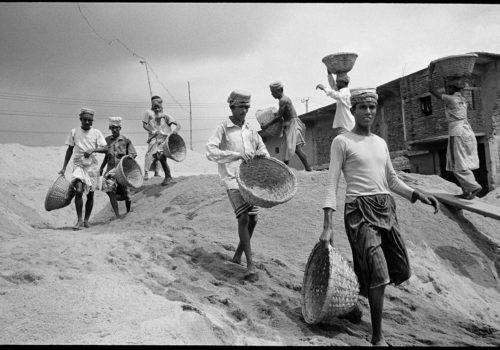

Michael Friedel started out as an amateur photographer, making his own way. The pictures he brought back from his first trips – hitchhiking to Italy and Greece – could, in retrospect, put him into the category of “humanist with a camera.” “I seek out real people,” was the motto of his early years. The work of this first period is characterised by curiosity, involvement, and a pronounced interest in social phenomena, but in a society’s compatibility rather than its confrontations. He captured life essentially as lived in the street, not contrived, but often enhanced with a hint of the surreal, as one contemporary critic had already noticed. Back then, Michael Friedel was his own boss, and in fact has been so throughout his life. Early on, he displayed an unerring instinct for subjects, situations and faces. This is beautifully illustrated by his shot of a mother picking lice from her son’s hair, right outside the local Communist Party office in Rome’s poor Trastevere district – personal hygiene under the eyes of Stalin and Togliatti. As Friedel recalls, this was his first “hit”, winning 1st Prize at the 1954 Photokina. He remained independent and self-employed in the second phase of his career, too. Neither at the illustrated magazine Quick(1957-1960), nor at Stern (1961-1968) was he on the permanent payroll. True to his aim for a journalistically involved and “authored” form of photography, he developed his own themes and then offered them to whichever editor was retaining him. And since the early 1970s Michael Friedel has been entirely freelance, now working as a dedicated nature photographer and globetrotter, author and consultant. Michael Friedel, once the sensitive observer, you might say, of Europe’s post-war generation, has become the portrayer of the world’s most desirable destinations. If nowadays the name of Michael Friedel stands for something, it is for his breathtaking images of our last remaining corners of paradise. Michael Friedel is the photographer who has revealed through his lens the Seychelles and the Maldives – still undiscovered worlds when he first visited them. Yet this has not been without cost – as his early reportage, his portraits and street-scenes, his sensitive and atmospheric pictures and early images of cultural life, have largely been forgotten.

In the early 1950s, when Michael Friedel, encouraged by his school-friend Max Scheler, began to take an interest in the medium, at a time when photography – other than just taking snaps – was at best either a craft or a branch of journalism . The much-quoted “Subjective Photography” championed by Otto Steinert, could not offer any lasting guidance. Henri Cartier-Bresson, with his Images à la Sauvette of 1952 (published in English as The Decisive Moment), was like a distant and unattainable comet.

Photographs were not hung in art museums, and photographic galleries did not exist. The photographic image was nothing more than a foundling of modern technology, a hobby perhaps, but certainly not a profession. No wonder then that Michael’s father, a respected attorney in Berlin and later Munich, was vehemently opposed to his son’s burgeoning interest. So there was no longed-for gift of a camera, no progress, no inspiration. But the young Friedel did find inspiration in Norbert Amann’s photo-laboratory in the House of Book Trades, in Munich’s Schellingstrasse, where the fretting high-school pupil had a year’s practical experience. Here he not only became familiar with photographic technology, but also got to know some of the big names in photography who dropped by – men such as Erich Lessing and Ernst Haas, who was later to become a lifelong friend and confidant.

What followed was firstly a Leica bought on instalments, and then a commercial traineeship with AGFA in Munich, which certainly did no harm to the later self-employed Friedel, when it came to managing his financial affairs. What also followed, more importantly, were his first black-and-white photos, which greatly impressed the jury for the Photokina Young Photographer competition. They also caught the eye of the art director Willy Fleckhaus, who gave Friedel – along with a talented cohort including Thomas Hoepker, Horst H. Baumann and Christa Peters – his first exposure in the youth magazine Aufwärts (Upward) and, from 1959 onward, in the newly launched magazine twen.

What is reportage? As once defined by Henri Cartier-Bresson, photo-reportage is “a continuous action in the head, in the eye and in the heart.” In exactly this way, Michael Friedel’s very first pictures show his empathy and a feeling for situations that were by no means always as “cheerful, funny, quirky ” as his brief biography in Stern claimed. Among colleagues like Thomas Hoepker (“the passionate analyst”) and Stefan Moses (“the objective critic”), Friedel was known as “the optimistic traveller”, which was true to the extent that Friedel never quite lost his faith in the world. To this day he prefers to capture sublime, sometimes awe-inspiring, moments. One such was the eruption of the unpredictable Irazu volcano in Costa Rica, as threatening as it was majestic, which made a lead story in Stern in 1965, and appeared a little later in Du magazine. What do not interest him are wars and conflicts, global death and destruction. One exception to this is his reportage on a camp in Saigon (Human detritus of the Vietnam War), published in the magazine section of Die Zeit (week 47, 1973), which certainly proves that Friedel can handle tough material when he has to. Michael Friedel knows how to tell a story in pictures. “The pictures must flow,” as Henri Cartier-Bresson advised him in Paris in 1953. And: don’t crop your photos. Keep the important thing in the centre. Michael Friedel has remained true to that guidance, without giving up his own signature style. His legacy of photographs was and is impressive in composition, even though he once said that the journalistic statement was more important to him then the aesthetic aspect. What is certain is that Friedel reflects his medium – the magazine .His images are entirely appropriate to the magazine context.

This carries right through to the bond which he, as the figure standing between the subject and the reader, always keeps in mind. But whether it was Elvis Presley in his early years, Sophia Loren on a film-set, Willy Bogner directing Iris Berben, Hildegarde Knef on stage, the up-and-coming Peter Handke at a Beatles concert, Rainer Werner Fassbinder taking a break, or Helmut Newton at a fashion-shoot – Michael Friedel was never a paparazzo, never obsessed with celebrity for its own sake. He was always concerned with creating strong images, images whose half-life would outlast that of the printed medium. Michael Friedel gets up close, following the maxim that “the best zoom-lens is your own two feet”; he uses ambient light and eschews flash, he senses and translates atmosphere into small monochrome masterpieces. His street photography is flanked by portraiture. His first essays – such as a series on young people in eastern and western Europe – are evidence of his talent in conveying the Zeitgeist though photos. More journeys, to the USA, Israel, South America and the Soviet Union, broaden his horizons. By 1967 Friedel had already visited more than a hundred countries, according to an extensive feature devoted to him in the Leica Photogaphy series ‘Masters of the Leica.’ Here one can already speak of the ‘travel imperative,’ which Friedel considers “the richest in experiences and the most rewarding.” He was referring to the fact that, as a rule, he financed his trips in advance, not least in order to be free in every respect, free to act and free to take photographs. But he was also talking about the joy of discovery, his desire, bordering on obsession, to explore the foreign, the remote, the mysterious, and to explain all of it in pictures to those who stayed at home. Among his destinations since the 1970s have been, again and again, the South Sea islands – distant worlds between “Heaven and Hell”, to quote the title of a book he published in 1978 under his own imprint. This no doubt made a significant contribution to the lasting image of Michael Friedel, “Island Photographer”, but at the same time overshadowed the rest of his work.

When still working for the Munich-based picture-magazine Quick, Michael Friedel attracted attention with his features on domestic German themes, such as a 10-page report on the deplorable conditions in hospitals, and another on the Austrian rock singer and actor, Peter Kraus, under the headline “Peter can’t help it if people love him.”. But it was when he had he moved to Stern magazine in 1961, that he became a camera-toting globetrotter. “He knows Rio, Bangkok and Acapulco as well as his own photo-kit,” proclaimed Color Photo back in 1975. But it was not only the hot-spots of imminent mass-tourism that interested the multilingual Michael Friedel – as much at home in Spanish and Portuguese as he is in English, French and Italian – but increasingly areas where indigenous peoples have been able to preserve the remains of their cultural identity. The high point was surely his expedition to visit the last aboriginal communities on earth, which he undertook with the author Rolf Bökemeier. The team spent almost two years travelling across five continents; in all, they covered some 50,000 miles. The result of their travels was the highly-praised book Lost to humanity: encounters with peoples who will be gone tomorrow, which GEO published in 1984 as a kind of epitaph to vanishing tribes.

Though Friedel has occasionally acted as a “destination-scout” for airlines such as Lufthansa, Condor and LTU, he has nevertheless retained a critical attitude to the postcolonial behaviour of high-spending tourists. It was this that prompted his sensational reportage on sex-tourism in northern Cameroon, published as a lead story in Stern in 1975 under the headline: ‘The whites are coming: big-breast hunting in Africa.’

His shot of a beaming German holidaymaker surrounded by young black women went round the world, to be endlessly copied and reprinted. It ultimately became Michael Friedel’s trademark – an iconic image that people know well, without being able to name its originator.

“I often work for months, even years, on one subject,” Friedel revealed in a personal statement in 1970. No, he is not the typical “roving reporter”, although the miles he has clocked up certainly suggest it. Friedel is a thoughtful craftsman, who sets off on his journeys well-prepared and leaves nothing to chance, aware that one only sees what one knows about. As a journalist he is a pro, which means, among other things that he can be relied upon to deliver. After all: “Excuses don’t get printed.” At the same time he is an adventurer, but not at all costs. He possesses a better nose than most for the macabre, but he also knows the limits of a story. His vast archive has to date been the source of some two dozen books, which he has usually published under his own imprint, including The Maldives (1992), The Seychelles (1993), Bali (1994) and Mauritius (1995).

Friedel’s images appear on Maldives postage-stamps, and on the Brazilian 10-Reais banknote (initial print-run 250 million). Readers of GEO magazine should know his name, as should those of Stern. But who looks at the credits? Michael Friedel is familiar without being famous. It is particularly his early work that awaits discovery and analysis in the context of a media history yet to be written. There the photographer Michael Friedel will surely find his permanent place. Even in the 1970s, in a series of advertisements for Stern, he was counted among “the world’s best photographers.” Decades later, Norbert Lewandowski calls him “one of the great photo-journalists of our time.” As a photographer, Michael Friedel has gone his own way; he has tried out for himself all possible options in documentary and reportage photography, finally taking on the role of international evangelist of earthly Edens. It is time to rediscover the poetry of his early images.

Hans-Michael Koetzle is a freelance author,

commentator, and curator of photography .

He lives in Munich.