In this essay, American author Jordan Teicher reviews the scandals that recently affected several fashion photographers and discusses their importance in the history of photography.

That a camera can be used to objectify and control people has been a widely accepted fact since essayist Susan Sontag published her 1973 polemic, On Photography. “To photograph someone is a sublimated murder, just as the camera is the sublimation of a gun. Taking pictures is a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time,” Sontag wrote.

The violence Sontag describes, naturally, is symbolic. But today, the times are sadder and more frightening, and a recent string of sexual harassment accusations against photographers has prodded Sontag’s notion, underlining the extent to which a photograph can be the result of violations both figurative and literal.

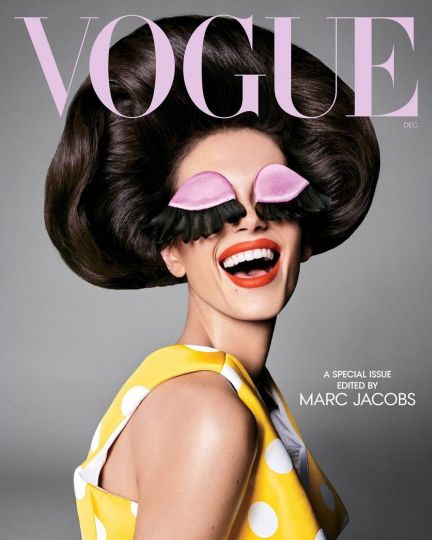

The accusations extend to the highest echelons of the photography world, including the fashion photographers Bruce Weber, Mario Testino and Anthony Turano. After accusations became public, Turano retired from photography, and Condé Nast cut ties with Weber and Testino. All three deny the allegations.

The implications for these men’s professional lives are clear. Like other prominent figures taken down in the #MeToo Movement, they will forever be associated with sexual harassment, and their careers will be irrevocably tainted. But how do the accusations impact the cultural artifacts these men have left behind? Can we disentangle their behavior from their work? Should we?

This isn’t, of course, the first time we’ve wondered whether to separate an individual’s creative work from his terrible personal behavior. Many people have tried to listen to Richard Wagner’s compositions without thinking of his anti-semitism, or tried to watch Manhattan without thinking of Woody Allen’s alleged sexual harassment. It’s not an easy task, but it’s possible. The work is the work, those people argue, and the person is the person.

But that argument becomes much harder to make the closer the bad behavior gets to the other people involved in the production of the work. And it gets nearly impossible when the work itself constitutes a realistic, visual and nearly instantaneous record of that behavior—the kind of record that Weber, Turnano and Testino’s photographs of their accusers inevitably constitute.

That’s why one can’t justifiably extricate Weber, Turano and Testino’s alleged behavior from the photos they’ve made: Because in many instances, the men’s accusers are also their photographic subjects. Turano allegedly offered models photos in exchange for sex, Weber allegedly molested models as he photographed them and Testino allegedly made “sexual come-ons” during shoots. Though the technical limitations of the camera leave this behavior out of sight, the men inevitably leave a trace of themselves and their alleged behavior in all these photographs.

In all portrait photography it is, of course, very difficult to extricate the photographer from the photograph. As American philosopher Richard Shusterman argues, portrait photography is not just a photograph but a “larger complex of elements,” a “performative process” that includes “a photographer, a human subject who knowingly and willingly serves as the photographic target, the camera…and the scene in which the photography session takes place.”

The interaction between the photographer and subject, Shusterman argues, is a crucial component in the production of a photograph—and it has “aesthetic import.” The core of this interaction, Shusterman argues, is the photographer’s mission to gain a subject’s confidence through body language that “must not be threatening” or “intrusive” but rather “friendly” and “intimate.” The photographer’s behavior toward his subject, projected in the photographer’s “somatic style,” then “infects the photographed subject as well, thus raising the quality of presence that can then be captured in the resulting photo.”

But what, one must wonder, if the somatic style the photographer projects to his subject isn’t friendly or intimate, but rather just the opposite? What if, as in the case of the fashion industry’s worst actors, the somatic style is characterized by sexual harassment or intimidation? It follows that this toxic behavior, too, must infect the subject, and must then be captured in the photo. It must render an aesthetic all its own.

That this aesthetic has for decades attracted the eye of the fashion industry—and the fashion consumer—is troubling, but it is not altogether surprising. Feminist scholars have long noted that ads often frame women as objects of sexual utility inherently subordinate to men. These critiques frequently cite what is visible within the frame of the photograph as evidence of this dynamic—the poses that “subtly demean the female subject” by suggesting that her body exists only for consumption by viewers. That these poses, which are choreographed to satisfy the male gaze, can also be assumed by male subjects is a revelation often attributed to Weber.

In advertising photos, author John Berger argues in Ways of Seeing, such poses contribute to the production of a fantasy that is strategically used to sell products to viewers. It is a fantasy, he proposes, that equates the power to buy with the ability to be “lovable” and “sexually desirable.” Berger is not wrong in that assessment. But his dialectic does not address the ways in which the process of producing that fantasy can be, in fact, an opportunity for some photographers to literally fulfill their own fantasies—one that can result in very real harm for subjects.

Photographers accused of harassment have admitted as much to this power play. “I was a shy kid and now I’m this powerful guy with a boner, dominating all these girls,” the photographer Terry Richardson once said of his experience on set. (Richardson was only dropped from Condé Nast this October, years after he was first accused of harassment.)

Richardson’s attitude is representative of many photographers in the industry who seem to relish the erotic potential in the photographer-subject relationship—a relationship perhaps best enshrined in the iconic scene in Michelangelo Antonioni’s cult 1966 film Blow-Up in which a fashion photographer straddles a writhing model as he photographers her.

The photograph may be a platform for play-acting sexual politics, but for sexually abusive photographers and their victims, photography’s performative process is not make-believe. This process takes place in a setting where photographers wield extraordinary power, and where subjects possess extraordinarily little, where the rules of conduct are blurry and where the mechanisms for reporting ill treatment have been historically limited. For the photographers, it is a particularly conducive setting for realizing deeply-held sexual desires. For the subjects, it is an environment where they are uniquely vulnerable. The stakes, for both, are tangible.

Other creative workplaces, it must be noted, present similarly unbalanced power dynamics. And as the #MeToo Movement has made clear, there isn’t a single field that is safe from that dynamic’s consequences, from theater to dance to music. Surely, sexual misconduct in all these arenas impacts the cultural product. But in photography we can see that impact—that is, if we choose to.

In her book, At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen, Shawn Michelle Smith argues that photography, from its very beginning, has “expanded the realm of the visible, but it also exposed its limits, both physiological and technological.” Those limitations are, she argues, often informed by culture. “Willful repressions and unwitting blind spots, both personal and collective, limit what can and can’t be seen,” she writes. By looking beyond the “edge of sight”—the frame of the photograph—we can begin to transcend those limitations in order to fully understand what we’re looking at.

It’s understandable, to an extent, why viewers have felt they couldn’t possibly peek behind the curtain of photography to evaluate the aesthetic qualities of its performative process. What goes on during a shoot—particularly a fashion shoot—is often done behind closed doors, and there’s traditionally no written record of the interaction between photographer and subject that outsiders can assess.

Now, however, we have such a record in the form of the testimonies of the men and women who have spoken out as part of the #MeToo Movement. They’ve opened a rare window into the elements of photography beyond the photograph—the words, the gestures and the unwanted touches— that have contributed to the making of many of the images that have defined an entire industry.

To ignore that testimony now is to not only turn a blind eye to assault, it is to fail to truly see.

Jordan Teicher

Jordan G. Teicher is an American journalist and critic based in Brooklyn, New York.