The late Mary Ross (1950-2012) was a fine art photographer, visual artist and teacher. In 1975, she began using video and computers to produce still images on film, one of the first fine art photographers to do so. Her images provide some of the earliest examples of the convergence of photography, video and computer technology. Recognized as a pioneer of digital photography, her photographs and video art have been featured in hundreds of multimedia performances she has produced in collaboration with composer/performer Eric Ross. She exhibited extensively at galleries and museums in the United States, Europe, Israel and Japan.

Her photographs are in private collections and in the permanent collections of the Kunsthaus, Zurich; International Polaroid Collection; Herbert Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University; King’s Library, Copenhagen; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; and the Lincoln Center Library Dance Collection. Her archive is at the Rose Goldsen archive for New Media Art at Cornell University and at LIMA in Amsterdam, Netherlands. An additional gift of Ross’s works and some by the late Joe Buemi were made in 2005 to Musee Reattu. Ross’s original prints went there in 1984.

With a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Mary Ross collaborated with choreographer Lois Welk of the American Dance Asylum on Parking Ramp Dance, an ongoing, site-specific modern dance work incorporating dance, music and projected visuals. Her permanent archive is at the Rose Goldsen Center for Art at Cornell University , among others.

Ross’s earliest video art used live cameras in closed circuit installations during music performances by Eric Ross. She manipulated video camera imagery during these concerts. This was an early example of music and video designed to be seen together. Since then, she had concentrated on producing works which have been designed, composed and edited to his music. These have been displayed and projected as an integral part of many live performances worldwide including the Kennedy Center, Newport, Berlin, Montreus and North Sea Jazz festivals, the Copenhagen New Music Festival, Prague Alternativa Festival, Festival Brussels Palais des Beaux Arts, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Los Angeles Redcat Center, among many others worldwide.

In the following interview with her collaborator, partner and husband musician and composer Eric Ross, Eric provides essential information in the history of digital photography.

Eric Ross has presented concerts of his music at Lincoln Center (NYC), Kennedy Center (Washington, D.C.), Disney Redcat Center (LA), Newport Jazz, and Berlin, Montreux and North Sea Jazz Festivals, among many others worldwide. He performs on guitar, keyboards and is a Master of the Theremin, one of the earliest electronic instruments. The New York Times calls his music “a unique blend of classical, jazz, serial and avant-garde.”

He began playing the Theremin in 1975, and has performed on radio, film and TV. Together, the Rosses presented multimedia performances with video, music and dance. Projects include an Ultimedia Concept program at UNESCO World Heritage sites including the Guggenheim-Bilbao Museum, Spain; Residenz Palace, Wurzburg; Bauhaus- Dessau, Germany; and Casada Musica, Portugal. He was a friend of Theremin virtuoso Clara Rockmore, and electronics pioneer Robert Moog. In 1991, he met and played for the inventor of the Theremin, Professor Lev Termen.

Q) How did your multimedia Pieces develop?

A) Mary and I started working together in the 1970s. In 1976, we first used live and pre-recorded video in my Songs for Synthesized Soprano (Op. 19). There was immediate synergistic energy to our combined work. Mary wrote, “In 1977, I began to use video in live multimedia performances in collaboration with my husband, composer/performer Eric Ross. At first I used live video cameras in closed circuit installations during performances of his original electronic and acoustic music compositions. Two or three video cameras were mounted on tripods and focused on him as he performed, inside the piano, and I manipulated video camera imagery with a glass prism. The results were displayed on two color TV monitors which faced the audience. Since then, I have produced pre-recorded videotapes and now DVDs which are designed, composed and edited to his music. These tapes, with accompanying video stills and digital images, have been displayed and projected as he performed concerts of his music worldwide. I wanted to create a parallel in the music to the video which would reflect and comment upon the action in different, distant and often remote ways. I like to set up contrasts with the music and images on the screen – fast when slow, bright when dark, dense when sparse – to create unexpected relationships and meanings. Eric’s music has led me deeper into this non-literal, non-narrative form. Musically there are specific themes for some parts and other sections open to improvisation. In performance, the music and the emotional relationship to the video, which is fixed, is ever-changing depending upon time, place and mood.”

By the 1980s, we were performing our pieces in major venues in the US and Europe. We worked with the space and equipment situations available. We performed in big rooms like the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Berlin, Montreux and Pori Jazz Festivals as well as smaller, more intimate rooms like the mirrored ICC in Belgium, the Munch Museum in Oslo and loft spaces in NYC.

Mary’s work evolved steadily. She was a darkroom printer in black-and-white and color film, and in other media including gum bichromate, silkscreen, and Polaroid. She saw video processing as an extension of the technical possibilities of print-making, or an “electronic darkroom.” She included slide dissolves and video during this period. She said, “The video synthesizer functioned as a type of electronic darkroom. My own slides, negatives, prints, movie film and videotapes provided source material.” At a certain point, technique and aesthetic merged and became intuitive.

In interviews we were asked, “Which came first: the music or the video?” Usually, we would work simultaneously and at a certain point of progress, would come together for editing sessions. From that point on, we would stay in close collaboration. Mary preferred to edit to my music – I would give her track to edit to, and then I would orchestrate the final versions for “mixdown.” Other times she would work alone on a piece until it was nearly complete and then I would compose music to it. We were open to different approaches and each piece shaped up differently. Our works were never experimental – Mary and I knew exactly what we were after in each piece and worked hard to get it right.

Q) Were there artists she was influenced by?

A) Mary knew the great European and American painters, the classic black-and-white photographers and all kinds of visual references. She was commissioned by universities to photograph art galleries and museums across the USA and EU. Thus, she was familiar with the works of the major artists as well as many other painters, graphic and visual artists, photographers, sculptors, etc. She had a “photographic memory” regarding images. She never forgot a picture and could recall names, places and details of photos or prints she had seen from decades before. Joseph Buemi, a classic black-and-white photographer, gave her occasional help and some darkroom tips and the two remained good friends despite their work being very different. She kept in contact with a network of video and film makers and was aware of work and tech developments in her field. She was an avid reader, writer and prose editor. All of these things formed background to her own work. She never wanted to be copy artist, a clone or from the “scuola de” style artist. She always sought her own identity and vision in art.

Q) What were the themes of her work?

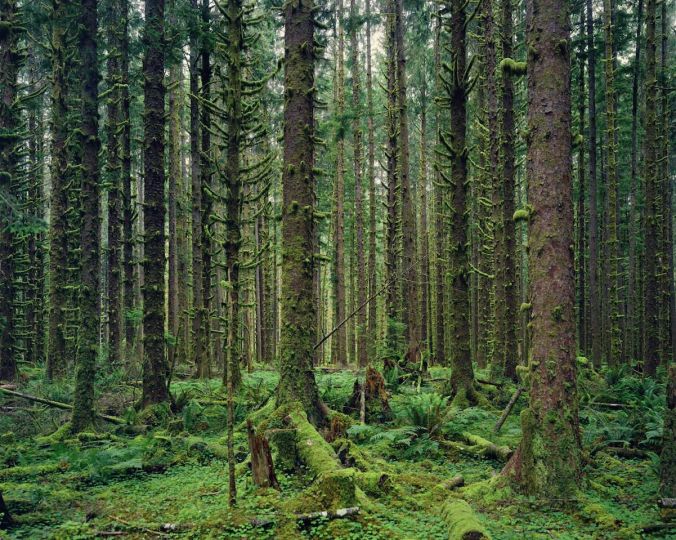

A) The major themes that Mary worked on all her life included: People Real and Abstract; Dance; Self-Portraits; and Imaginary Landscapes. She received a National Endowment for the Arts Grant for her work with dancers. She was very aware of “negative space,” the spaces between things. Most of her images fit into these categories, although she would take a photo of any subject if it pleased her.

Q) Did she storyboard her videos?

A) Almost never. She improvised in the camera, in the studio, and in her editing, mixing and finished work. She knew what she was after, recognized what she actually had, and went with the work where it took her. Because of her great visual memory, she could find and combine edits from materials that were perhaps years or miles apart. She could work on different sections, or from the inside out, to shape the materials. It was a process as well as a product. Mary knew what she wanted in the final print. I don’t think anyone else could have predicted from the source material, or even mid-stream, how the final images would look.

Q) What was her working method?

A) Mary was constantly shooting, editing, evaluating, filing, re-evaluating and re-editing. She shot a lot of film and later digital images, but she was often a one-shot picture-taker. Even her video shots were mostly single-takes. Editing was her forte. She edited herself – always selecting, refining and mixing. Sometimes she liked to let the computer make random mixes, putting together images like musicians “jamming,” and then remix that. Her final edits were always carefully chosen. Mary seldom took the first version of a shot. If she liked something, she would keep working it, sometimes over the course of years, changing things minutely or entirely – adding, subtracting, changing in different media, etc. She liked to work on many projects at the same time and this helped to “cross-pollinate” her ideas.

Q) What were your last collaborations?

A) Mary and I created dozen or so works for video and music. By our last pieces, the Blvd Reconstructie (Op. 54) and Rimn Vornl (Op. 37, 2011 Edition), she had a real sense of the architecture of her time-based art on the micro, middle, and macro levels. She used her own autobiographic materials as a girl, a woman, a wife, a mother, a cancer patient and an artist, with concert footage, travel, dance, human abstractions, family, friends, black-and-white stills, Cibachrome color prints, super 8mm films, gum bichromate prints, silkscreens, Polaroids, watercolors, distressed images, images with text, hand-drawn and hand-colored prints – everything relevant to her life – all in the mix. Ideas that she had worked on during her entire career came together and were interwoven in these last pieces.

Q) How do you see Mary’s artistic development?

A) I think all of the elements of her vision were present early on. She refined her vision by focusing in on the ideas that she loved and that would convey her artistic objectives. She acquired technical mastery over her tools as well, and these tools (home computers, video cameras, etc.) became simpler and more easily accessible over time. In the early years this was not always the case, but she had always “worked with what she had,” or as she might say, “fought with what she had.” Mary had periods of time that were real growth spurts and others that seemed fallow where she did many different things but were in fact “in developmental” stages ready for the next artistic endeavor. She stayed true to her art and her last works were a combination of her ideas with many layers of energy going on, both simplifying and gaining in complexity.

Q) Why do you think her is work important?

A) Mary had an aptitude for getting a great shot or sequence of shots that spoke to the viewer on different levels of interpretation. She said, “The images create a narrative that can be supplied by the viewer’s imagination.” Her mixing of imagery was precise, yet free, strong and beautiful. Her vision was unique from a woman’s point of view without being self-consciously so. Her sense of composition and drama within a shot was enhanced by an expressionist palette, which makes her images even more striking. There is a timeless quality about her work. Some figures in her shots seem to be floating or in suspended animation. Her work was never totally “abstract.” She said, “The human form is a recurring motif…along with many images of dance. Though often abstracted, my photographs and videos usually contain recognizable elements. In recent work, I continue to explore abstract renditions of the human form in imaginary landscapes.”

In some of her pieces, there is a calmness and quiet of infinite spaces, where time seems suspended and there is an air of tranquility. In others, she deliberately introduced chaos, noise, glitches and other random elements to create a sense of real and unreal; there is movement, the action is in flux, and she went for the vital significant energy of the moment. She liked to capture energy, mood, setting, characters, time and place. She was not fascinated by technology for its own sake – she was interested in the human aspects of art and art-making.

Michael Foldes (b 1946) is an American poet, publisher, author and businessman. From 2005-2019 he published Ragazine.cc, the free global online magazine of art, information & entertainment. He lives in Upstate New York.