“My body and its peculiarities, which I was born with, had, I believe, a significant impact on the process of creating and finishing my work.”

Mari Katayama, sporting a ginger bob and round glasses, sits by her computer, embarked on a gentle yet focused attempt to answer my questions via her pixelated screen. During that Corona-ridden spring, we are both confined to our apartments – mine shines in broad daylight while hers is already engulfed in darkness. This rising star of the contemporary art scene casually allows me to enter her Japanese living room, which is filled with a child’s laughter. Her young daughter, popping in and out of the screen, bears a radiant smile, wriggling in and out of her mother’s arms. “It feels like it’s my responsibility as a mother to finally take an interest in human actions” confesses Katayama. With this pandemic, she thinks the awareness of our bodies’ fragility is gaining ground and that the link between the environment and our bodies become painfully evident. I ask her to what extent this has impacted her work – she hesitates, unsure where to begin.

Mari Katayama, born in 1987, is a versatile artist, best known for her self-portrait photography. Winner of the Kimura Ihei Prize of Photography in 2020, her attention to detail stands out: she single-handedly crafts the rag sculptures she adorns herself with, the interior decors, and inlaid objects which are all part of her work. She suffers from Tibial hemimelia, a malformation of the legs is, in her case, accompanied also by the malformation of one hand. At the age of 9, she decided to have her legs amputated. While she says that she does not use her disability as a source of inspiration, strictly speaking, it remains inseparable from her work.

Winner of the 2005 Gunma Biennial of Young Artists Encouragement Prize, she propelled into the world of contemporary art thanks to curator Takashi Azumaya’s support. In 2012, she continued her studies at Tokyo University of the Arts under a renowned mentor’s guidance, who happened to be none other than the contemporary artist Motohiko Odani. Her work deals with the question of identity, or rather with the issue of a disjointed, eclectic, or even erased sense of self. Through manipulating a fragmented body, she conveys her own life experience. Soon, an exhibition entitled Home Again at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie will be dedicated to Mari Katayama’s work. Due to the current health-crisis, dates have yet to be confirmed.

Mari Katayama’s work is embedded in an artistic movement that can be traced back to the postwar Japanese era, where the representation of the body manifests a kind of social anxiety and a tear in the fabric of identity. Following the defeat against the United States, Japan embarked on an accelerated development of its capitalist society. The ensuing unbridled growth of mega-cities combined with the quickly developing new technologies fundamentally challenged the position of the individual within society. Internal migrations dismantled rural communities; the nuclear family structure gradually decreased in size and social inequalities intensified, particularly after the stock market crash of 1992. More and more citizens, alienated by endless working hours and the urban epidemic of loneliness, are now finding refuge in social media.

Today, the climate crisis shifts the spotlight to our interdependent collective bodies: we face the urgency of reinventing a relationship with the environment without falling prey to individualist consumerist practices. While thus experiencing an uprooted relationship to our own bodies, we are at the same time inextricably linked to the “social body” and the world surrounding it.

The objectified body

When discussing her past works, Mari Katayama acknowledges that the way she displayed her body in the past differs fundamentally from her current approach. She tells me that she initially perceived her body simply as a kind of matter: “Rather than as a body, I saw it as an object”. This objectifying view could, of course, be a result of the oppressive gaze placed on disabled bodies by society.

The gaze of others upon our bodies naturally influences our self-awareness: it either welcomes, or stigmatizes us. The disabled body, which does not conform to the norm, often attracts the eyes of those whose paths it crosses – with curiosity, pity, but also with disgust. It is this combination of curiosity and judgement that is characteristic of what people with disabilities constantly have to face.

When asked about this particular issue, Mari Katayama sounds deflated, growing tired at the mere recollection of how non-disabled people have imposed their gaze upon her:

They were just looking at my body, my appearance. I think it’s the same as looking at a face to determine whether it is beautiful or ugly. It’s wrong.

This perception of the disabled body as fundamentally alien to the able-bodied self has fuelled the fear-mongering around disability in the cultural and broader social sphere. In his book on disability in Japan, the sociologist Iwakuma Miho explains that the public’s desire to stare at people with disabilities does not involve any desire or necessity to interact with them[1]. This avoidance is reflected in research: in Japan, Mari Katayama’s native country, only 1% of the disabled people who could work are provided further training. Few of them can find work, as almost half of the companies do not exceed the mandatory quotas. This strenuous employment process indicates a lack of accessibility to training and workplaces, thus reflecting a lack of understanding of disabled people’s needs. Not giving disabled people access to the public sphere is equivalent to their erasure.

[1] 岩隈美穂 IWAKUMA, Miho, “Being Disabled in Modern Japan: A Minority Perspective”, in Kramer, Eric Mark (ed.). The emerging monoculture : assimilation and the “model minority”, Praeger Publishing, Santa Barbara, 2003, p. 131

Mari Katayama, red cover (2008)

The thus erased disabled body slips into a void, which Mari Katayama manifests in red cover (2008), one of her early works.

The title refers to what is “concealed” or covers the body and traces its edges. Red cover is a flash photograph taken at night of a bench on sandy ground, on which two pieces of red fabric are placed. Upon closer inspection, one realizes that the two pieces of cloth are cut in the shape of Mari Katayama’s amputated legs, and are placed on the bench where her legs would be if she were seated there herself. The blood-red color is reminiscent of an injury – in this case resulting from the amputation of a limb. It attracts attention and generates a kind of morbid fascination in the eye of the beholder. Here, Katayama highlights the voyeuristic gaze of non-disabled people who perceive disabled persons only through the prism of their disability or injury. In this photograph, Mari Katayama only exists in the shadow of her amputated limbs.

This internalized gaze heightens the pressure of fitting into the collective as much as possible. Indeed, the disabled body attracts attention precisely because it represents a deviation from the non-disabled norm. As Katayama experienced first hand when she was bullied at school, this unwanted attention can turn into violence.

It was then that Mari Katayama developed a growing desire for assimilation with her peers through mimicry. She speaks of the obsession to “fix herself” during her teenage years, as a way of getting rid of unwanted attention. This desire to assimilate implies a need to control one’s own body and space.

Mari Katayama herself claims to have developed total control over the creative process of her work. This involves the staging of the set, the photographic framing, and even the orchestration of her exhibitions. Mari Katayama masters each and every step of the creative process, meticulously crafting her sets and costumes, framing the photo itself before capturing the shot, using a self-timer. “Playing” with her different bodily experiences related to the use of prostheses (or lack thereof), Mari Katayama tries to capture the “perfect” image:

I stage the set that is on display in my works – sometimes by putting on my prostheses, other times by removing them, in a controlled manner. […] after having installed everything using my prostheses, I removed them on purpose: I thus created a balanced installation, regardless of the point of view.

This conquest of the body and the space it occupies comes at the cost of expressing a kind of physical vulnerability – that is, a position of physical weakness inevitably referring to her disability. This rejection of fragility goes hand in hand with the training of her own body as a site of artistic experimentation .

Therefore, the body appears to be a manufactured product, a simple vessel of our existence – a “mannequin”, says Mari Katayama as she reminisces on her past works. She turns her body into an object, from the project’s conception to its execution and final presentation. Thus, the body is seen as material, as texture, akin to a red piece of fabric.

The journey from internalizing another’s gaze upon her own disabled body all the way to the expression of a yearning for normalization takes place in terms of the total control over the body, a body seen as an instrument to be fixed. The carefully staged representations of her body will have served to conform to the non-disabled standard – if only on the other side of the viewfinder.

Multiple bodies and dreamed identities

In the mid 2010s, Mari Katayama confesses having used her work to dream of what she might have been under other circumstances:

[…] I saw myself as one of my imaginary characters. I didn’t think it was another side of me. Today I wonder if maybe I was forging a better life for myself.

In her series shadow puppet (2016), several self-portraits bear witness to this exploration of otherness. In these pictures, she is wearing misshapen human-sized rag legs : the imagination of “what might have been” takes shape through expansion.

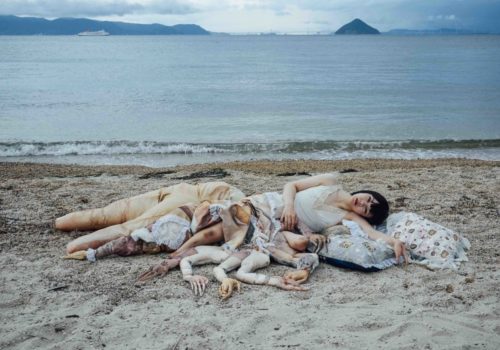

Mari Katayama, shadow puppet #015 (2016)

Mari Katayama, shadow puppet #016 (2016)

Mari Katayama, shadow puppet #019 (2016)

The title shadow puppet is revealing: these photographs are reflections of her shadow selves, unreal and therefore inanimate. In shadow puppet # 015, Mari Katayama portrays herself as a housewife with an apron tied around her waist, smoking a cigarette after a long workday. In shadow puppet # 016, she poses as a guitarist, composing a tune in front of her desk. She fantasizes herself as an effortless beauty in shadow puppet # 019, lying on a bed surrounded by fairy lights. However, realism is not sought here. The legs she “puts on” look more like a massive pair of pliers, echoing the shape of her left hand : one can even notice the nails drawn on them. Moreover, the walls around her repeatedly display crustacean patterns taken out of magazines – elements which accentuate the surreal aspect of these scenes and suggest the world of dreams, or imagination, as much as everyday life.

Here, the imagined experience of a potential, inaccessible existence is the very foundation of “otherness”. This fantasy of the “other” also encouraged the systematic mimicry practiced by Mari Katayama. This incorporation of the other, in the etymological sense of the term, shaped her perception of herself “I am a patchwork of other identities”, she says in an interview with Fragments Magazine in 2015. Here, the erasure of her body’s boundaries leads to a scattered sense of identity.

This is also found in the ambiguous form of the self-portrait : Katayama is both the object of her work as well as its omnipotent architect, exercising absolute control over each stage of the creation process. She oscillates, in fact, between an active and a passive determination of the identity she projects in her photography. The erasing of the boundaries between object-body and subject-body is also linked to the very essence of photography: any photograph of the body, delimited by its frame, presupposes for this observed body, an observant one. The frame is the porous boundary that separates these two bodies, and Katayama finds herself in both spheres, caught up alternately by her own gaze or by her own image.

In Mari Katayama’s 2014 you’re mine series, the permeability of the self-portrait’s frame is particularly eviden .

The very title of the project reveals a process of dispossession and of reappropriation of the self. The personal pronoun “you,” followed by the possessive pronoun “mine,” indicates a seizure of power, in which the persons involved are deliberately kept vague. Is it the photographer who is the one grabbing the object in front of the viewfinder, or is it the model who is taking over the observer’s identity? This ambiguity is always present in Katayama’s perception of herself within her work. Aware of the fundamental contradictions present in her creative process, she hesitantly attempts to establish boundaries: “When I complete a piece, it means that I have completed myself. […] But I have to tell myself that my work is not what I am “. The work operates as an extension of herself, and once it is completed, the bond between artist and self-portrait becomes ambiguous. The dynamics of power and ownership become uncertain, as reflected in the use of vague possessives.

This series’ staging in Tokyo expressed this ambiguous rapport within the four walls of the small TRAUMARIS space.

Mari Katayama, you’re mine #001 (2014)

On one of the walls hangs a photograph of Mari Katayama, lying on white cushions against a backdrop of white sheets sheets. She is assuming a classic pose, resting on her elbow, the other arm extended along the curve of her body as if she were on a couch. She is wearing gray stockings and a beige lace leotard. Her black bob is adorned with a straight fringe, her nails are painted red; she is wearing lipstick and a thick layer of eye-liner. She does not smile, with her lips parted. She poses seductively – the title you’re mine taking on an erotic meaning.

Just below this self-portrait, Mari Katayama places a human-sized doll that mimics the pose taken in the picture above. The doll is lying on a white sofa full of cushions. The imitation goes so far as to replicate the shape of Katayama’s limbs and the texture of her hair, but her face has been transformed into a vanity mirror with light bulbs to illuminate the onlooker’s face. On the opposite wall, a mirror reflects the scene.

Mari Katayama, Mise en espace de you’re mine, Traumaris (2014)

Mari Katayama, Mise en espace de you’re mine, Traumaris (2014)

Other self-portraits are displayed in the room, but the exhibition’s heart lies in the strange triangle formed by these three objets d’art. The mirror reflects the photograph and the doll, whose face is itself a mirror. Mari Katayama thus constructs an environment that never ceases to reflect her image (and as the doll’s face-replacing mirror suggests, this process of reflection finally takes over the image itself). This installation continuously poses the question of the “real body.” As she enters the room, Mari Katayama finds herself in four different bodies, both object, and subject of the gaze. Caught between all these representations of herself, her body expands beyond its physical limits, to the point where there is no longer one single body. The original body disappears.

Paradoxically, by expanding her physical boundaries to include other artworks causes to breaking her into fragmented pieces. Indeed, by projecting herself onto these multiple surfaces, Mari Katayama experiences a kind of fragmentation.

This inability to experience a grounded identity undermines the authenticity implied by the self-portrait.

Mari Katayama regularly stages herself in her bedroom or in her daily living spaces. These places are imbued with a certain intimacy – an impression reinforced by the messy decorations and a partially stripped model. This staging of herself in her personal space echoes a more global trend present on social media. Some see it as a form of exhibitionism, in the sense that users are encouraged to share their privacy, in a carefully designed environment in order to be admired and “followed” by subscribers. This “exhibited intimacy” is based on a fundamental contradiction: the picture that seizes a particular moment is later edited and reframed, in the keen awareness of its future reception by the public. These two moments are temporally dissociated but are tailored to create the illusion of simultaneity, as if the user were opening a window into strangers’ lives in real-time. However, this dissociation reveals the inauthentic character of the image: nothing is real there, not even the experience of sharing a moment with the voyeur. The exhibited intimacy loses its authenticity because it is no longer based on a moment shared in real-time.

Mari Katayama plays precisely with this gap that exists between authenticity and the performance of intimacy while taking full ownership of the artificial dimension of her intimate staging: “[…] I think that the subject of any artwork is fake. This is [applicable to] all works “. What we see is artificial, or at least incomplete, and is only the product of a back and forth of projections between the artist and her audience.

Nothing here speaks louder than her work mirror (2013), a black and white self-portrait taken in her bedroom.

[1] FISCHER-BARNICOL, Lou-Naëma, op. cit.

Mari Katayama, mirror (2013)

Mari Katayama is pictured perched on a stool in front of her desk, her legs resting on a stack of books to her right. Hair in a bun, she is wearing her prosthetic legs, as well as a set of leopard print underwear. Knees bent, arms crossed, her face is turning away from the camera and facing the mirror on the desk. Her plier-shaped hand is resting on her shoulder, and the other is only visible in the mirror, which reflects her illuminated face. In terms of composition, the photograph is centered on this mirror, which becomes the work’s focal point. In this mirror, we see Mari Katayama tilting her head, her non-disabled hand following the curve of her arm. Outside the mirror’s frame, her disabilities are highlighted, notably through the presence of her prostheses. Her room has also become an exhibition space for objects used in other artworks, like the piece of cloth used in red cover. A dichotomy arises between the mirror, which reflects an innocuous portrait, and the rest of the decor, which overexposes a disability otherwise absent from the reflection. The mirror is a mise en abyme of the photograph’s very frame, presenting only a manipulated, deceptive reality. It may be tempting to think that the bedroom is an “authentic” reflection, unlike the mirror, but Mari Katayama tells us with this title that the picture itself is a framed mirror. She plays on this deceptive ambiguity, knowing full well that authenticity is missing on either side of the mirror.

This disengagement from her work’s truthfulness leads Katayama to further explore the boundaries of her body, fragmented to the extreme.

The body, anchored in an environment

In 2016, however, a significant shift occurs in both her work’s conception and execution. Confusion sets in, and despite the detachment that Mari Katayama carefully cultivates with regard to her self-portraits, it is with melancholy that she tells me:

[…] I have to tell myself that my job is not what I am. I try not to think about it too much, I can’t tell myself it’s me. Because, well, to see yourself passed from hand to hand, it’s sad.

Witnessing the acquisition of her self-portraits by collectors, Mari Katayama may be expressing nostalgia for a part of herself that remains only inside the frame, trapped in the past.

This return to an anchored body can be traced back to the 2016 series bystander and on the way home. Bystander was produced within the framework of the Setouchi Triennale, the prestigious contemporary art festival held every three years on the archipelago located in the Seto Inland Sea in Japan. On the way home was produced immediately afterwards, and exhibited the following winter at the museum of Katayama’s native Gunma prefecture. She travelled to the islands off Seto to carry out her work – a first approach highlighting the fundamental importance of the environment when it comes to identity. :

What interested me the most was the life of people living on islands with different backgrounds. After all, in order to get closer to people’s existence and daily lives, we need to get to know their history and their surroundings.

In the course of this search, Mari Katayama discovered the environmental issue to be central to our relationship with our bodies. After alienating herself from her own body, she went on to explore these islands’ environments.

She was struck by the pollution ravaging the land and its inhabitants: “The main reason why I chose these places relates to my interest in people who have no other choice but to live in these polluted environments ”. There is a reciprocal link between the body and its environment that leads to the question of how our bodies can inhabit such hostile environments, but also, how we can inhabit a body forged by such polluted ecosystems.

In on the way home # 005, Mari Katayama poses on the edge of a body of water, her own body entangled in a cluster of ragged limbs. The piece shows her sitting in a quarter turn to the right on a chair, surrounded by reeds. Her expressionless face is smeared with dust, her eyes rimmed in black. Behind her, we catch a glimpse of an abandoned boat, stranded in the reeds. On the ground, we can distinguish the rubbish as well as tin bars.

Mari Katayama, On the way home (2016)

Mari Katayama poses in a landscape which is, at first glance, full of natural elements, and sends us back to rural imagery. Upon closer inspection, however, we notice this environment’s degradation in the form of cast out debris. Buried under parasitic limbs, Katayama’s own body reflects this and showcases a landscape eroded by the waste produced by human beings. Mari Katayama identifies herself with this polluted environment:

If the current environment has taken shape through what people have accomplished throughout history, I think, in that sense, that my physical body and this environment are much the same.

Mari Katayama could refer to her amputation in childhood, which shaped the current state of her limbs. The human hand shapes the environment as the artist’s hand shapes her own body. This is why Mari Katayama has chosen to adorn herself with so many arms and hands: “All is created by the human hand, and can be destroyed by the human hand”, she asserted in Paris in November 2019.

Her identification with her broader surroundings could also explain her focus on marine imagery and crustaceans. Indeed, Mari Katayama finds a form of kinship with the crab, symbol of the astrological sign of Cancer under which she was born, but also an animal whose claws remind her of the shape of her own hand. The incorporation of marine motifs in her work reinforces her identification with this particular environment.

Mari Katayama, bystander #014 (2016)

In bystander # 014, we can see Mari Katayama, stretched out on a beach, surrounded once again by her ragged limbs, her head and left arm resting on two cushions with shell motifs. Behind her, waves are gently breaking against the shore. We spot the silhouettes of other islands on the horizon and a ferry sailing the waters. Here, Mari Katayama conjures up the shape of an octopus, washed up on the shore – as are so many whales and other marine life due to the pollution of the seas.

As part of this project, Katayama discovers that her body, torn between various imaginary projections, now finds a sense of belonging within its environment. Bodies and worlds interact, change, and reciprocally absorb their reflections.

By exploring the link between the body and its environment, Mari Katayama begins her return to an anchored body. This journey back to herself continues to nourish her production, so that after on the way home, her next exhibition at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris will be entitled Home Again. And the birth of her daughter in the summer of 2017 only enhanced this new interest. During our interview, she explains:

I think environmental issues currently influence my work, and I think I have been aware of this since the birth of my daughter. […] I think [this connection between the body and the environment] is getting stronger right now.

The birth of her daughter accelerated Mari Katayama’s ecological awareness. It coincided with her move to her native Gunma prefecture, near the Mount Ashio copper mine. Due to her experience of motherhood with its share of obligations, her relationship to the environment became stronger: “[…] it is as if it was my responsibility as a mother to finally be interested in human actions”. This is when Mari Katayama experienced a change in the perception of herself and of her own body, as if she was experiencing a rebirth through motherhood. Childbirth allowed her to re-establish a visceral link with her own body, no longer limited to being a mere vessel:

[…] following the birth of my daughter, I think I became aware of my body, of the fact that it was I who was reflected [in my work], the body of my child’s mother.

Following the physical experience of childbirth, this renewed awareness of her body upset Mari Katayama’s relationship with her own image: “[…] I began to feel that the person I see in my work is me, it is my daughter’s mother ”. Her work is a throwback to her physical identity as a mother, offering her the physical anchor that she had so far discarded.

And so, after years of maintaining a fragmented body, Mari Katayama attempts to reassemble it. The quest for identity is relaunched:

[…] since my daughter was born, I consciously search for the one who is reflected in the viewfinder, and I wonder who this person is.

Her work, which is at a turning point, reflects this search: “I feel like I have started exploring other forms of self-expression through my art following the birth of my daughter”. In her 2019 series cannot turn the clock back, Mari Katayama explored a form of self-portrait stripped of all artifice.

Mari Katayama, cannot turn the clock back – surface (2019)

In her dorsal triptych cannot turn the clock back – surface (2019), Mari Katayama exposes her naked back on a golden canvas. The title suggests that we cannot go back in time, be it in the movement that this triptych delineates, or more broadly within the framework of Mari Katayama’s artistic approach, forever changed after her daughter’s birth. In the first self-portrait on the right, Mari Katayama glances back at the camera, her body slightly turned to the left, her disheveled hair sweeping across her face. Then, she turns completely away from the camera. At last, her head slumps, disappearing behind her shoulders. Mari Katayama’s back is contorted in these pictures, drawing our focus on the details of her ribs, her spine, her shoulder blades. Her body seems particularly tangible to us here, as if we could almost feel her flesh. To reinforce this impression, the lighting used emphasizes the shadows drawn by the valleys of her frame. “[…] In my later works, […] I aim to use only my simple body,” she says.

Body uncovered and rediscovered through the experience of childbirth, it finds its place in an environment with which it continuously interacts. Motherhood and environment intermingle to create a new bodily experience.

Through motherhood, Mari Katayama’s body is anchored in a process of universal regeneration: “I want to be aware,” she says, “of the fact that I have taken part in this process of human reproduction”. By achieving such a return to her own body, and by focusing on her physical experience, Mari Katayama reaches the foundation of humanity: “[…] it is by touching on this human experience of reproduction that my awareness of being human has blossomed ”. The essence of the universal is found in the particular physical experience.

This experience of childbirth is also reflected in the way she approaches her work: “I bring my work into the world, as I create it”, she says, drawing a parallel between motherhood and her artistic practice. The disabled body, through Mari Katayama’s viewfinder, is no longer so much an expression of insurmountable otherness as it is a common physical experience.

Mari Katayama’s latest exhibition focuses on isolated body parts, exposed and presented in a large format.

Mari Katayama, in the water #001 (2019)

The title in the water’s (2019) is self-explanatory: Mari Katayama is sitting above the river that runs through her town, located near the Mount Ashio copper mine, whose fumes have contributed to massive deforestation and water pollution. Here, the picture focuses on her legs, which she has sprinkled with golden glitter. Again we find the theme of the environment, which is superimposed upon the disabled body. But this time Mari Katayama goes a step further, asserting her corporeality by reproducing it on a large scale. She explains that it is precisely through her daughter’s gaze that she now sees herself in a new light, devoid of her own judgment related to disability. This allows her to find a more straightforward and more immediate relationship with her body, unburdened by social pressure.

Mari Katayama’s vulnerable and sober presentation of her body parts reflects something that we all recognize within ourselves : a fragile, exposed body, falling prey to its insecurities. It is in this sense that Katayama claims to have “a universal body” in an interview with IMA magazine.

This body also allows her to consider a broader range of perspectives, both physically and mentally. She pays particular attention to accessibility issues, in every sense of the word:

I would like to create an exhibition space accessible to everyone, on foot, or in a wheelchair. […] I think that both my body and my psyche have an impact [on my creation]. I always envision the worst and the best. Also, when it comes to the physical dimension, I try to balance what is seen at the bottom, on the ground, with what is on the ceiling.

Through her creative process, she aspires to make her work as accessible and universal as possible. Her physical body, the subject of her work, is in dialogue with the bodies of her audience, in a space that encourages their interaction. Beyond her physical body’s universal quality, her body of work also becomes a shared space.

Mari Katayama’s work resonates with what we are collectively experiencing. The body is at the center of all collective issues, from accessibility and privilege, all the way to the body’s imprint on its environment. Even in the throws of the Covid pandemic, our bodies are the centerpiece of public discourse, inhabiting the artistic productions of our time.

Mari Katayama cuts a further breach in the exploration of the body and its infinite forms in photography. She allows us to explore the ambiguity at the core of an artist’s relationship to her disabled body, without being trapped into a single aspect, be it that of alienation, objectification, or acceptance. She offers us a nuanced and rich perspective of the relationship with the disabled body. By letting go of control and rediscovering her own body, Mari Katayama truly surrenders to that “other” who transcends her : our collective body.

Lou-Naëma Fischer-Barnicol