On the eve of its 25th anniversary MAMM opens the new exhibition season with the exhibition Primrose. Early Colour Photography in Russia. 1860s—1970s. For more than twenty years the museum has acquired images that can be attributed to early colour photography for a special collection in their archive. Very little of this material was preserved. Technologies were constantly improved, making production less expensive and less time-consuming, however, early colour was often fragile and short-lived. MAMM showed works from this collection for the first time at the ‘Photobiennale 2008’ in Moscow, then in 2013 at the FOAM (Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam), and in 2014 at The Photographer’s Gallery in London. At the time the exhibition consisted of some 140 photos. Today the MAMM collection, which is constantly developing, contains about 800 works demonstrating the origin and development of colour in Russian photography from the 1860s to 1970s.

This new exhibition includes 248 works and a slide show by Boris Mikhailov. MAMM researchers have worked long and hard to prepare texts on the authors of the images and the events reflected in them, as well as about the history of photographic techniques used at different stages of the development of colour in photography.

The ‘Primrose’ exhibition shows how technologies that allow the images to be filled with colour appeared and evolved. The exhibition is also a brief summary of the history of Russian photography over a century (from Sergei Levitsky, Alexei Mazurin, Elena Mrozovskaya, Karl Bergamasco, Peter Vedenisov to Vasily Ulitin, Peter Klepikov, Alexander Grinberg, Alexander Rodchenko, Yakov Khalip, Georgy Petrusov, Vsevolod Tarasevich, Dmitry Baltermants, Boris Mikhailov, Alexander Slyusarev, etc.). At the same time the exhibition allows us to trace how life changed in a country that was experiencing historical and socio-political disasters, and the diverse roles photography played during that period.

Experiments in the creation of colour photography have been conducted almost since the appearance of the photograph itself. However, the widespread use of colour in photography begins with the 1860s. In the 19th century the colouring of black-and-white photographs with watercolours, gouache and other paints was the dominant technique.

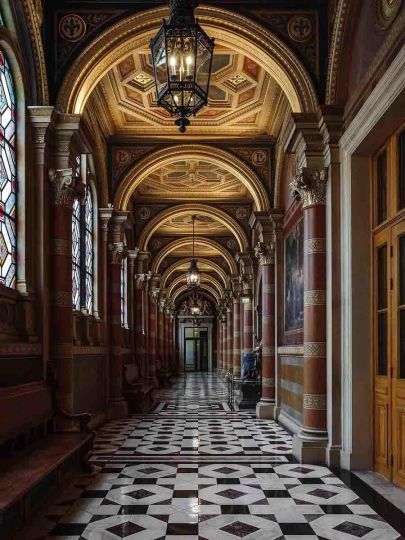

In 1903 the inventors of cinema, the Lumière brothers, patented a new process for creating colour photography — the autochrome. Potato starch granules coloured in red, yellow and blue were applied to the glass plate. The pellets worked as colour filters. The superimposition of a second layer of granules gave orange, purple and green colours. Then a sensitive emulsion was applied. Autochromes allowed sufficiently rich colour reproduction, but did not permit the creation of an imprint. They could be viewed through light or projected using special devices, which were also manufactured by the Lumière Brothers’ Company. From 1907 the Lumières began producing autochromes industrially (up to 6’000 per day). These were distributed around the world, including regular delivery to Russia. The remarkable photographer Pyotr Vedenisov had a weekly order for autochromes to be sent from France to his home in Yalta, from 1910 to 1914. His very private and personal shots of family members and close friends turned out to be one of the best expressions of the typological way of life of enlightened Russian nobles in the early 20th century.

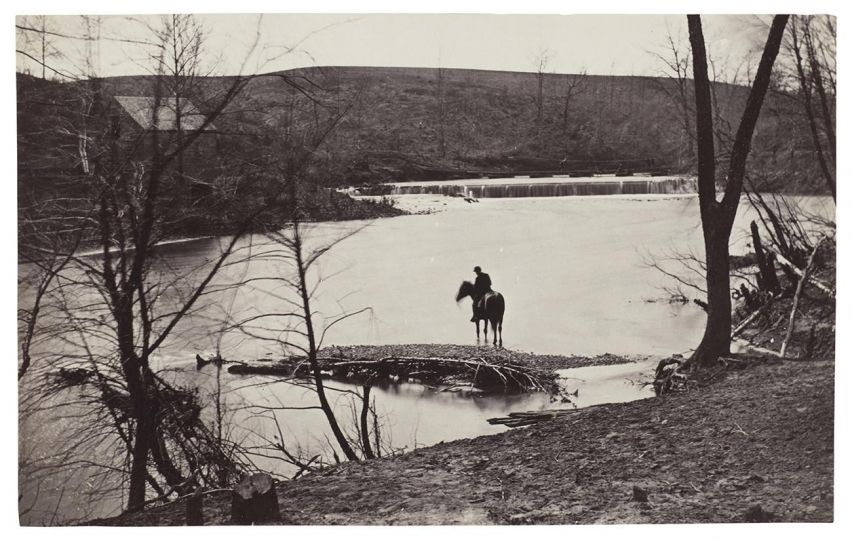

In Russia Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky became a pioneer of colour photography. In 1905 he developed and patented his own sensitizer (a substance that increases the sensitivity of photographic films or photographic plates to colour rays). Among Prokudin-Gorsky’s numerous achievements in the field of colour photography is the reduction of exposure, as well as the development of technology for replicating the image. Prokudin-Gorsky’s most famous series is his ‘Collection of Sights of the Russian Empire’. The photographer began working on it back in 1904, but the project acquired renewed scope in 1909, after Prokudin-Gorsky demonstrated his works to Emperor Nicholas II, a great lover of photography. The photographer received at the disposal of the Emperor a specially equipped car with a dark room for developing and printing pictures, as well as a permit that helped the photographer reach the most remote and inaccessible parts of the Russian Empire. Thereby Nicholas II supported the first large-scale work on the creation of a colour photo chronicle of Russia. The First World War prevented its further development. After the revolution Prokudin-Gorsky emigrated to Britain and later moved to France, where he began working with the Lumière brothers.

In the 1920s photographers from the two largest and competing tendencies in domestic photography showed interest in colour in photography: the pictorialists and modernists. From the mid-1920s to mid-1930s they revived the forgotten technique of hand-colouring photographs. Above all these were Vasily Ulitin, a pictorialist who participated in major international photo exhibitions and received medals and diplomas in Paris, London, Berlin, Los Angeles, Toronto, Tokyo and Rome, and also Alexander Rodchenko, a modernist and founder of the Soviet photo avant-garde. MAMM is the only museum to possess coloured photos by Alexander Rodchenko in their collection.

In 1936 colour photographic films appeared almost simultaneously from the German Agfa Company and American Kodak Company. Their wide distribution and entry into the amateur market were postponed due to the outbreak of the Second World War.

The production of domestically produced colour film in the Soviet Union was established with the help of captured German equipment in 1946. Before that colour photographs in the USSR in single copies were shot on German or American film. Until the mid-1970s negative film in the USSR that allowed for printing colour photographs was a luxury available to only a few official photographers working for major Soviet publications. It was used by such classics of Soviet photography as Vladislav Mikosha, Georgy Petrusov, Dmitry Baltermants, Vsevolod Tarasevich, and others. All of them, one way or another, were forced to follow the canons of socialist realism and engage in staged reporting. Even Ivan Shagin’s still lifes with fruit from that period carried an ideological load, being filmed for cookbooks in which a Soviet person could see what did not exist in a hungry post-war country, where the card system of food distribution had not yet been abolished.

From the end of the 1950s, after the debunking of the cult of Stalin’s personality during the Khrushchev Thaw, the canons of socialist realism softened and brought a certain freedom in aesthetics, allowing photography to move closer to reality (Dmitry Baltermants’ series ‘Arbat Square’, 1960).

In the 1960s and 1970s colour transparency film appeared on the market in the USSR. Unlike colour negative film, which required a complex and expensive development process for subsequent printing, colour transparency film could also be developed at home. It was widely used by amateur photographers. Photography became one of the most widespread hobbies among Soviet people in this period. Almost every house had a slide projector. Home projections with the obligatory discussion of pictures were a popular leisure pursuit.

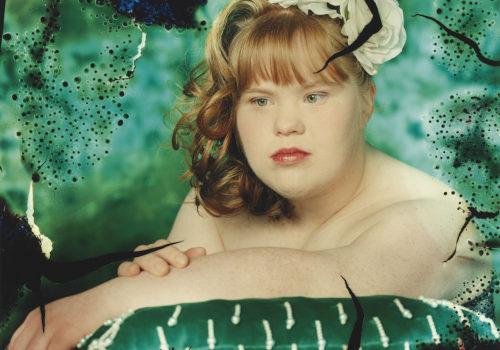

At the same time unofficial art emerged in the USSR, an important part of which was unofficial photography. In the 1970s Boris Mikhailov, one of the most famous Soviet photographers worldwide, shot the series ‘Suzy and Others’ on colour transparency film. Boris Mikhailov’s slide projections, created for a narrow circle of friends and like-minded people, were an analogue of the apartment exhibitions. In the work of Boris Mikhailov colour is used conceptually, revealing the dull uniformity and squalor of surrounding life.

During the post-war years life in the USSR gradually improved. Once again there was a demand for coloured photo portraits ordered specially as a memento. As a rule they were made by ‘illegal’ photographers, since the private photo studios that had carried out such commissions from the second half of the 19th century were banned by the 1930s. The state exerted a complete monopoly on photography. In the 1980s Boris Mikhailov referred to the aesthetics of kitsch colour photographs ‘as souvenirs’ in the series ‘Luriki’. With his colouring of naïve photographs he showed and deconstructed the nature of Soviet myths.

We have included in the exhibition two series by conceptual photographers Boris Mikhailov and Alexander Slyusarev dating back to the 1980s, when the authors yet again brought colour to photography by hand-colouring pictures, just as Alexander Rodchenko had done fifty years previously, in the 1920s and 1930s. The artistic worlds of Boris Mikhailov and Alexander Slyusarev were completely different, but they arose at the same time in unofficial Soviet art, when the aesthetics of Moscow conceptualism continued to develop in the postmodern era.

Curators: Olga Sviblova, Elena Misalandi

Primrose. Early Colour Photography in Russia. 1860s—1970s

2 September 2021 — 15 November 2021

Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Ostozhenka, 16

Moscow, Russia