Given a one-way ticket from Chicago to Melbourne in 1961, photographer Maggie Diaz arrived on the docks with just five bucks in her pocket ready to start a new life in a new land. “I remember asking myself at the time, Jesus what have I done?” she laughs her voice still tinged of a New York drawl. But more than fifty years later this fast-talking, fiercely independent woman has made Australia her home and is finally gaining recognition for an oeuvre that spans generations.

Born in 1925, Diaz’s life, pre-photography, was colourful to say the least. In her late teens she travelled around the Deep South of America as a performer with Harry Blackstone’s Magic Show, assisting the magician in all manner of tricks. When she got tired of being on the road she tried her hand as an illustrator before landing a job with an advertising photographer in Chicago who taught her how to process film.

In the mid-fifties Diaz picked up a camera and took to the streets of Chicago taking photographs of “anything that was different, things that you didn’t see in the newspaper. I always had my camera with me and I used to give the kids in my neighborhood milk and cookies in exchange for taking their photo. After a while they got used to me and would follow me calling, hey lady you wanna take my photo? Being out on the street taking photos made me feel connected”.

One of her favorite memories of Chicago is taking photos at the Tavern Club, an upper class establishment on Michigan Avenue where artists and intellectuals rubbed shoulders with the city’s elite. “I had such a good time photographing the Club’s musicians in particular, like the Ramsey Lewis Trio. You know they were so pleased with the photos and I was amazed , I never expected it”. The Tavern Club provided a rich source of characters, both performers and patrons, that feature prominently in her work from that period.

From Chicago to Melbourne

In 1961 Diaz travelled on the maiden voyage of The Canberra arriving in Melbourne in the middle of winter. Her passage, a one-way ticket from her ex-husband, an Australian graphic designer she’d met in Chicago, was uneventful. “Although I did all my money in Hawaii”, she confesses, leaving her virtually broke.

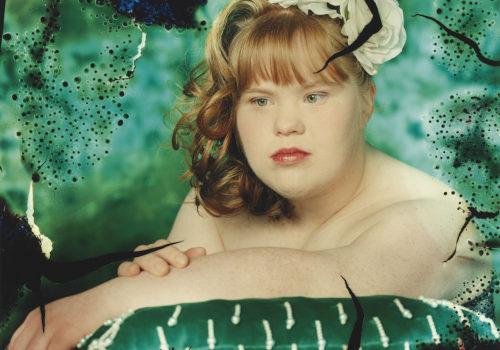

In Melbourne in the 1960s there were few professional photographers and Diaz’s previous experience earned her a variety of assignments for a host of clients as she turned her hand to everything from fashion and advertising to social documentary. “I was good at talking to people, making them feel comfortable. I have a strong feeling for human beings, and for those on the outer,” she says of the poignant images she captured particularly working on assignments for charities and welfare groups.

Favoring natural light, Diaz created a signature look that is evident throughout her work, which comprises a large number of portraits. “Once you start to move light around…” she shakes her head. “A person’s got many faces, and flaws. I always attempted to capture that wonderful thing that makes one person different from another and using natural light helped me stay true to what I was seeing in that person”.

Walking into Melbourne’s photography scene armed with her portfolio, international experience and an “attitude” didn’t endear her to her peers, the majority of which were men. “I was the Yank, and a woman,” she laughs at the memory of the horror they must have felt at her bravado and clasps her hands in glee. Tall and intimidating, Diaz wore pants and had the audacity to stand up for herself. She recalls times shooting at public events and being jostled by the men in their fervour to get the shot before she did.

“They tried to push me off the sidewalk! But with the kind of experience I had at home nothing terrified me. You know you have to hold your own and at that time there would have been maybe one or two female photographers and a lot of times they’d leave it for the guys to get the shots. But that wasn’t me.”

An Enduring Partnership

To write an article about Maggie Diaz and not mention her long-time muse, friend and curator of her collection, Gwendolen De Lacy, would be to leave out a huge part of the Diaz Story. De Lacy says the pair first met at Diaz’s photography studio when she was 15 years old. “Studio, hah, it was an old dump,” interjects Diaz in her rasping laugh. De Lacy continues unfazed. “Our first photo shoot was twelve hours,” she says. “I went to Maggie for my acting portfolio. We got to know each other through the lens”. “We are best friends,” they agree. Since that first meeting more than 25 years have passed and the pair is virtually inseparable.

De Lacy tells that they haven’t gotten to Diaz’s colour work yet. “We’re still on the black and white and have catalogued around a thousand images so far”. It is a labor of love. Amongst the haul are Diaz’s portraiture work and her streetscapes. In the early years in Melbourne, Diaz would often be out at night with her camera, observing and documenting the city, warts and all. As a consequence she photographed a broad cross section of the city’s inhabitants on her trusty Rolleiflex. “I used a Rollei because it always worked, I didn’t have to think about it,” she states.

In the sixties, drawn to the culture and music, Diaz gravitated towards the Spanish quarter in the inner Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy. There she met her long-time lover and their union produced a son. Their relationship was unconventional by the standards of the day, Diaz was older by ten years, and the pair never married, but being different is something that Diaz has identified with all her life, she tells.

“I always felt more comfortable with those considered on the outside of society – that’s where I’ve always seen myself. I’ve used photography to investigate society, the differences between cultures and the migrant experience in particular. I find it fascinating.” She laughs, “I’ve always been a bit crazy”.

Diaz also ran a portraiture business from her studio shop front, and as a subject children were a favorite. “There are so many things that can happen with a child, they don’t hide their emotions. I liked to photograph children, but I was always sensitive to the mood of the child and if they didn’t want to have their photo taken I’d tell their mother to bring them back another time when they were ready”.

Better Late Than Never

Through De Lacy’s sheer tenacity, Diaz’s collection is finally finding critical recognition and Diaz has exhibited several times in recent years. The National Library of Australia has a number of Diaz images in its collection, and the National Gallery of Australia has recently acquired her works much to Diaz’s surprise and delight.

Diaz may lament never having returned to the US, but her adopted home has gained an extraordinary artist. I still find it amazing that she is only now being recognised. I ask her what it’s like to have all this attention, finally, after all these years. She laughs, her voice rich and deep.

“It’s all consuming, it’s fantastic. There are a lot of people who wouldn’t believe this. They’re probably saying what’s an old bitch like that fooling around with photography for, has she still got all her marbles?” She shrugs. “Who woulda thought?”

Maggie Diaz’s photographs can be seen at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra and limited edition prints can be purchased from her archive.

A permanent collection is on show at Graze on Grey in the Melbourne beachside suburb of St. Kilda where Diaz lives.

Alison Stieven-Taylor