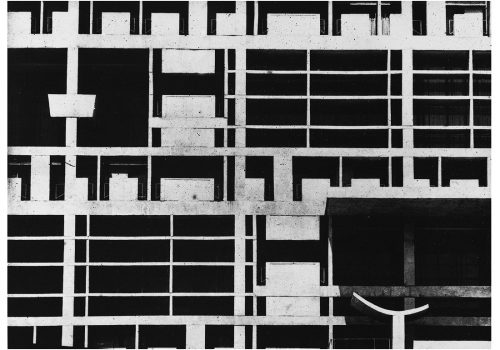

A retrospective at the Jeu de Paume in Tours spotlights the work of the photographer Lucien Hervé who made geometries of the world his mantra. His elegant play of light and shadow reveals man-made architecture.

“You have the soul of an architect.” These words were uttered by Le Corbusier, a friend of the photographer, with whom Lucien Hervé developed a life-long collaboration, showcasing his buildings in exceptional cuts and shapes. And yet, early in life, Lucien Hervé had dreamed of being a painter, and continued to seek out patterns like an impressionist.

Everything began in Paris in the 1930s. Lucien Hervé, aged nineteen, a Hungarian born in 1910, set down his luggage in the French capital. He would soon discover photography.

His early works, featured in the exhibition, show a distanced approach to his subjects. From the balcony of his seventh-floor Parisian apartment he captured the passersby: soldiers, people cycling, running… He called these photographs PSQF, “Paris Sans Quitter ma Fenêtre,” or “Paris Without Leaving my Window.” He took photos of fleeting silhouettes that, for a moment, inhabit public space: the nape of a woman’s neck as she sits by the Seine and whom we can just barely make out; the legs of Louvre visitors waiting by the museum entrance; a shadow crossing an abysmally empty avenue.

“He sought geometry”

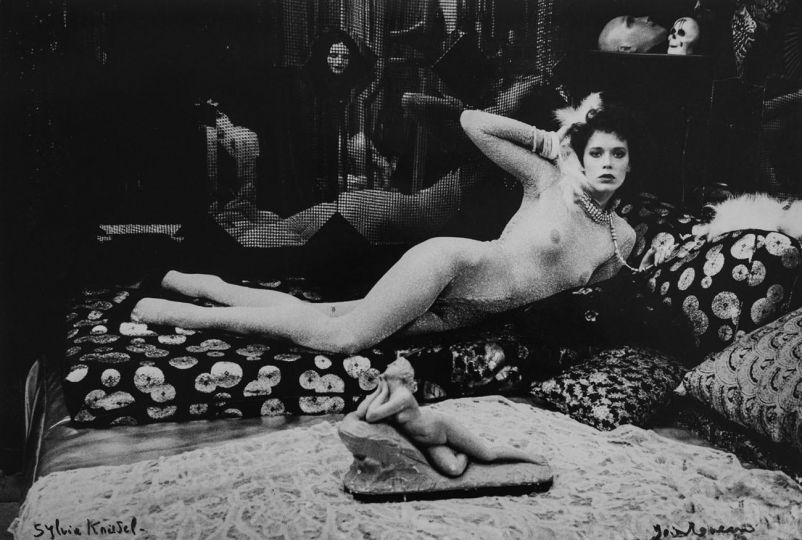

Lucien Hervé masterfully plays with light and shadow. A champion of black-and-white photography, he never hesitates to heighten the contrast. This is true of the image entitled L’Accusateur [The Accuser] which represents an Indian child leaning against a wall, his face veiled by the shadow of the awning. The portrait of his friend Le Corbusier is another example: the architect is seen in profile as his outstretched arm touches a concrete wall—his own work—and looks past the embossed figure of the Modulor. The image is transected by a giant shadow. “He was seeking geometry and rigor. He hated the anecdote,” remembers his wife Judith Hervé, “naturally, this geometry is everywhere. Including in portraits.” In 1949, Lucien Hervé immortalized Henri Matisse in the artist’s studio. He focused on the posture of a master of modern painting. He photographed one of his hands. In the exhibition, this image is displayed next to some more intimate portraits from the photographer’s life: a pair of legs, naked shoulders… “Lucien Hervé would sometimes crop his photographs,” explains Imola Gebauer, the exhibition curator. “He could thus easily highlight the forms he aimed for, reveal the bodies, as well as the geometry.”

Palmyra

In the early 1950s, the most geometric among photographers became the official photographer of the famous architect Le Corbusier. Lucien Hervé regaled himself of his friend’s constructivist buildings. He knew how to bring out their sharp edges, spherical curves, their immensity, as well as the utopian character of modern housing. Although this became the photographer’s specialty, he never abandoned ancient architectural styles. In the 1960s, he traveled to Greece to photograph the Parthenon and the Acropolis. He visited Persepolis in Iran as well as Palmyra in Syria. He has given us an image of the Temple of Bel (now destroyed by ISIS). He went to Spain where, moved by the recent war, he immortalized small white houses of the local peasantry. As a leisurely traveler, he brought back landscapes that may be structured or in ruins. His eye was always drawn to patterns of marked geometry, where one can discern a certain graphic structure. This approach was intensified in series done in view of a book publication, later prefaced by Le Corbusier.

“An architecture of truth”

The book bearing this title centers on the Thoronet Abbey in the Departement of Var, discovered thanks to Le Corbusier. Lucien Hervé may have found there the ideal location for his art. He elegantly captured the solemn character of the place. As his wife recalls, when he said in a TV interview that he was an atheist, the journalist replied, “it is hard not to believe in something when one looks at your images.” Le Corbusier said that the abbey possessed an “architecture of truth,” and that his friend Lucien Hervé knew how to bring out its essence.

Even more touching are perhaps the last photographs he took after he had been diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. From the 1980s through the early 2000s, Lucien Hervé, who could no longer travel, began photographing fragments of his apartment: the glass shower door; the ceiling decorated with patterns from a Mondrian painting; a section of his library… These color photographs say a lot about a man passionate about design and capable of finding beauty everywhere, including in the most intimate of interiors, his own home.

Jean-Baptiste Gauvin

Jean-Baptiste Gauvin is a journalist, writer, and stage designer. He lives and works in Paris.

Lucien Hervé, Géométrie de la lumière

November 18, 2017 to May 27, 2018

Château de Tours

25 Avenue André Malraux

37000 Tours

France