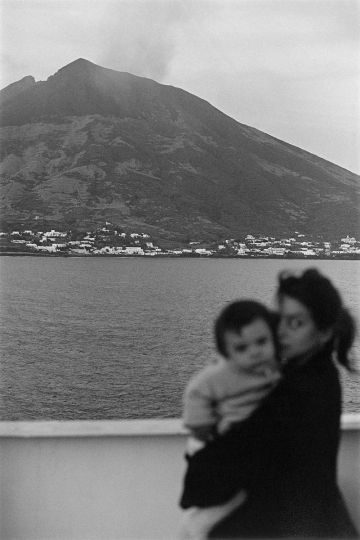

Swiss photographer Luc Chessex lived in Cuba between 1961 and 1975. He worked for Cuba Internacional. The Cuban news agency Prensa Latina designated him as the correspondent for Latin America and sent him on missions with the editor-in-chief. After a short stay in Chile, where Salvador Allende had just been elected president, he went to Bolivia, where the government had just lifted the travel ban in the zone where Che Guevara’s small group was ambushed. Che was wounded in battle and, the following day, assassinated. The photo of his body, exhibited for twenty-four hours in the laundry room of the Vallegrande hospital, circulated around the entire world. The Cuban government wanted to find the remains of Che and give him a burial worthy of the role that he had played in Cuba. After three months dedicated to following his Bolivian route, in a hostile atmosphere, all efforts only lead to the discovery of a wristwatch and a pipe that had belonged to the Che. His body was finally found in 1997, in a mass grave near an airport in Vallegrande.

In addition to these derisory objects, Luc Chessex returned to Cuba with one question: how was Che, considered as the most important guerrilla strategist, able to commit the fatal error of attempting to start an armed struggle in a territory where it would have no chance of taking root? The only relationships the guerrillas had with the countrymen were limited to the food that the countrymen supplied to them before informing the army once their backs were turned. How could Che make such a grave error?

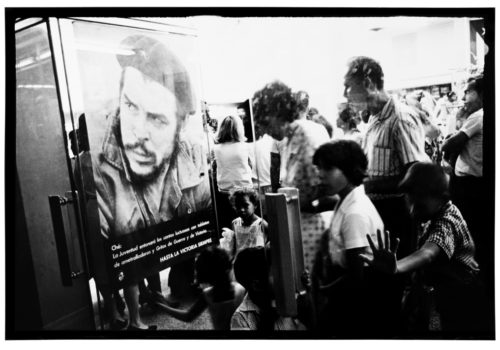

On the way back home to Havana, he found the ubiquitous photo of Che, floating along the fields and streets of the Latin-American cities and villages. He recounts in this book: “Two icons quarreled over the Latin-American countryside: the elixir invented in Atlanta in 1886 by the pharmacist John Pemberton and the image of the revolutionary Che Guevara. From one side, ‘a sign on good taste’, and from the other ‘Hasta la victoria siempre/Make two, three, a lot of Vietnams’ as an answer to ‘things that go better with coke’. The battle was fierce and ruthless. The man who, in an irrational suicide, a sacrifice of self, only succeeding in provoking the suspicion of the Bolivian campesinos, had suddenly become the flagship of youth determined to break away from the established order. According to Régis Debray, a rich misunderstanding: ‘the antiauthoritarian revolt of 1968, from Paris to Berkeley, took, as its banner, this supporter of excessive authoritarianism. A wave of permissive and naturist sensibility, raising to the sky a dogmatic Puritan.’ ”

Luc Chessex, Coca Che

Published by Editorial RM, Mexico

650 pesos

http://www.editorialrm.com/2010/product.php?id_product=385&id_lang=1