A horse is a horse, of course, of course not. Last weekend in May this year, a band of twenty-five auspicious, advantaged and likewise (unsurprisingly) ideologically possessed women galloped, neighed, scratched their “hooves” in the dust and peeved their way through Stockholm during a two-hour-long protest against the “Patriarchy”. “Our performance is a fun way to confront it [by posing] viewers the question of how women can occupy the public domain without being objectified,” the City Horse choreographer explained to the Svenska Dagbladet daily. “Horses are a symbol of power, but at the same time they represent equestrianism and dance – both female activities which are often marginalised. And just like the female body, horses can symbolise both the restrained and the wild.” The cortège gaited around centuries-old equine sculptures and the insignificant lives of (white) males of flesh and blood.

Like Roland Barthes wrote in Mythologies, “toys always mean something”. So really, what is this thing about women and girls and the second sex, the horse? “We press against the striking stallion, throw our arms around his neck – we kiss him on the nose – and tell him how beautiful and gallant he is. It is all so innocent – and yet we are learning about the elusiveness of affection, about beauty and longing,” as AM Homes swoons in Jill Greenberg’s starkly carnal and so elegant photobook Horses from 2012. “At night we dream of rescue, of being delivered from our lives to this more beautiful, more perfect place, the dark knight charging through the forest. The unicorn under a full moon. The raven-haired woman riding bareback by the sea. This is a world where good triumphs over evil.”

When all the handshakes between the races of the Universe are over and done with to Bowie’s “Space Oddity” in Luc Besson’s Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017) we are four hundred years into a future on the paradisiacal planet of the oh-so beautiful, androgynous Pearls and their companionable, fabulous pets the Mül converters (as they are called), a creature that poops mother of pearl and who has the inner power to restore a pastel Eden. Sophie Mörner is the curator of Like a Horse at Fotografiska in Stockholm and she has dotted the corners of her show with alchemic horse manure. “The exhibition is more than an exhibition and it represents everything I wanted it to be” is her one comment. Mörner’s selection of equine photography is generous and playful, concentrated and quietly passionate. She brings us the fellowship, the freedom and debauchery of equestrianism, the legacy and contemporariness of the horse, and the silver spurs of identity politics and its miserable luxury of solipsism.

“Horses once held a slightly mystical connotation for man. Physically, with their perfect movement, they seemed to contain an element of divinity. Seated astride them one could move at great speed – almost fly. What does that mean now to the motorway driver? Yet there is a difference, and perhaps when we have come to terms with scientific advancement we shall gain a better sense of values. Hopefully, this might bring a new confidence – another rebirth bringing with it new creative artistic activity,” suggests John Baskett in his book The Horse in Art. “There is, on the other hand, an aspect of the animal that has appealed to the more sophisticated requirements of human nature – the need for excitement, for aesthetic satisfaction and as an expression of spiritual aspiration. To be seated on a horseback, five feet above contradiction, brings authority, to gallop hell-for-leather with the wind in you face lends the rider wings, as if one with the gods.”

Like a Horse, is like that scene in Scorsese’s greatest film Goodfellas (1990) in which the gang is having dinner with Tommy’s mother (played by Catherine Scorsese) who shows them her latest painting with the dogs. Tommy: “I like this one. One dog goes one way and the other goes the other.” Mrs DeVito: “One’s going east, the other’s going west. So what?”

So what plenty: Like a Horse is going one way with the choice photography and the great stuff about the romance with this really big pet, about the effort of being present as much as being in touch with what our ancestors knew, and hence raising us to a more commendable level, and certainly about females expressing their own power. And it is going the other way with the demagoguery of the feminist narrative on gender politics – dominance and submission, don’t you know – and the pathological rules of sexist formulae and ghastly old Freud all over again.

Sophie Mörner claims that she wants to undo the clichés of cowboy masculinity. Or something like that. “My focus is to lift the woman and playing with the concept of queerness. For me the horse is both masculine and feminine, dominant and submissive, mastered and wild [italics mine]. But the notion of masculinity in what is widely regarded seen [sic] as a women’s sport or hobby, is interesting to me,” she states on the wall text which is the same as in the Like a Horse book, a smaller but great compilation of the pictures in the show published by Max Ström. As a Manhattan publisher of Capricious magazine with sixteen issues so far and the grand High Tails in 2014 (the Year of the Horse in the Chinese calendar), perhaps Mörner should have known better than to use Jill Greenberg’s words above as if they were her own. This is the curator in the press material: “The culture of equestrianism and horse sports is often vilified. It’s interesting to ponder how this is connected to the fact that it’s a phenomenon that is related to women and girls. I think of this exhibition as a reflection of Western prejudices about ‘the sport for privileged girls’.” Mörner got her first horse when she was ten.

“The horse went into a semi-retirement with a part-time job as a recreational item, a mode of therapy, a status symbol, and a source of pastoral support for female puberty,” writes Ulrich Raulff in his Farewell to the Horse memorial in which he considers horses to be the most noble of creatures, even “more spectacular in their suffering”: “Standing in their stables like living sculptures, they would nod their shaped heads, signalling distrust or suspicion with a twitch of their ear. The horses had their own pasture, to which never a cow would stray, to say nothing of the pigs or geese. No farmer would consider surrounding his horses’ meadow with the barbed wire which was often used to enclose sheep and cattle. For the horses, a bit of wood or a simple electric fence was sufficient to stop them escaping. One does not incarcerate aristocrats. It is enough to remind them of their word of honour.”

One of Ilona Szwarc’s schoolgirl amazons from her excellent Rodeo Girls series (2012) has a full-size cardboard figure of John Wayne in the corner of her bedroom. (Wayne was afraid of needles and horses – so much for that cowboy machismo.) One horse goes one way and the other goes the other in Camree and Chaynee, Canadian, Texas (2012) with these seven-year-old twins astride. Their tiny bodies are not much bigger than the heads of these animals and still they have the clout to master them. It is like Jean Cocteau’s sibylline words one hundred years ago in Cock and Harlequin: “The little girl mounts a racehorse, rides a bicycle, quivers like pictures on the screen, imitates Charlie Chaplin, chases a thief with a revolver, boxes, dances a ragtime, goes to sleep, is shipwrecked, rolls on the grass on an April morning, buys a Kodak, etc …”

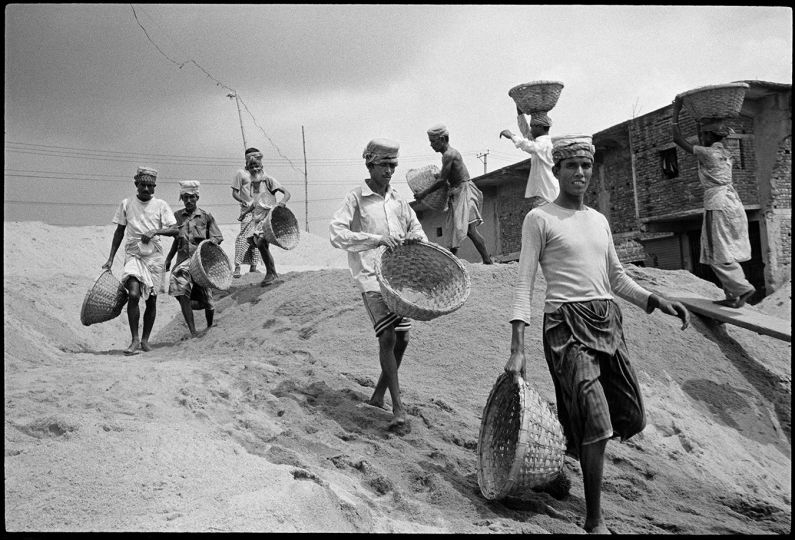

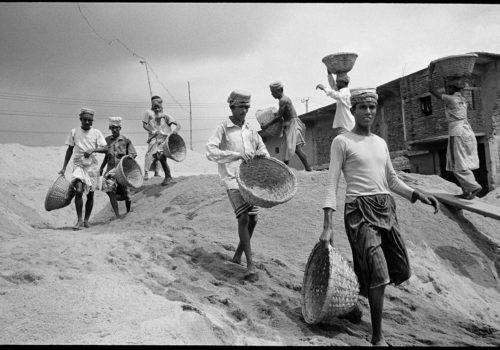

Szwarc who grew up behind the Iron Curtain in Warsaw in the 1980s was lucky to have a father who was an airline pilot. In her teens, she spent a year as an exchange student in this small town Canadian on the Texas panhandle where she encountered the rodeo business. During her recent trips to Texas (and to Oklahoma and New Mexico) as an artist living in the States, Szwarc discovered a whole new culture of young girls taking part as professional rodeo contestants. “I found their spiritual and emotional connection with their horses very beautiful. They loved the feeling of being one with the animal,” she told National Geographic (May, 2014). The little women in these powerful small photographs (taken with a large-format camera) are both tender and rough-handed. Mörner: “These girls have a different approach and attitude to femininity and traditional gender roles. Engaged in activities that have historically been reserved for men, they display strength and dominance over the animals.” The reality is that the horse industry in the US generates a far greater share of GDP than Hollywood or the tobacco companies, and that the rodeo business stops at nothing in order to incite the horses for this brutal form of entertainment.

Two girls have written “Love horses!!!” with a marker pen on their forearms in Theresia Viska’s black and white documentary series Stallflickor (Swedish for stable girls), which came out as a photobook in 2006. Viska claims to avouch herself in the “animalism” and the “unbelievable courage” of these “three-apples-tall seamen”. It is true that shovelling manure in a stable isn’t the most glorious assignment and that there are injuries aplenty in dealing with horses and that being on a horse is more dangerous than being on a motorcycle. But women are also more than welcome to play with the concept of queerness when it comes to the grimy, gruelling and hazardous duties that men perform every day and then and always under the yoke of traditional demands and female acquiescence.

Horses can survive almost everywhere and in any climate. But how much human can a horse put up with? In the sensitive documentary Buck (2011), the original “horse whisperer” Buck Brannaman, who was badly abused by his father as a boy, explains that he is “helping horses with people problems”. Craig Cameron’s call in Ride Smart is to “Realise that horsemanship is all about working on yourself, not so much working on the horse. The horse is a rhythmical, balanced, patient, trustworthy and consistent animal. It’s you who needs to develop feel, timing, rhythm, balance, patience, consistency, and understanding.” In The Domestic Horse, Daniel Mills and June McNicholas direct attention to the horse as an anthropomorphic plaything and refer to a 1983 study which reported “that the majority of riders considered their horse to be part of the family and that most related to the horse as if it were a child (although there was a suggestion that male riders more frequently relate to the horse as an adult family member). However, despite this childlike projection, they would confide in it and speak to it as if it were a person of the same age.”

Signe Johannessen has supported her altar to the horse with hay bales. In her “stable” at Fotografiska there is also a video with horses looking at this affectedly dramatic pile of skeleton parts from their own species. I don’t know what this thing is doing in a building dedicated to great photography, but the meta level of the video made me think of the Norwegian children’s film Oskar’s America (2017) in which the gentle village fool Levi takes his white pony – or Horsie as he calls it – to a birthday screening of a film called The White Horse. (Then there is young Oskar himself who dreams of horse riding with his absent mother in Monument Valley.) Mörner: “Providing an opportunity to reflect on the impact of humanity on other species or the concept of race itself, the work highlights issues about prevailing power structures.” I am sure that these unidentified “power structures” do not include the misandria and eugenics of Swedish feminism.

But there are works by thirty artists in Like a Horse and most of it is good to very good. In Ridley Scott’s latest (and mediocre) Alien film Alien: Covenant (2017), one of the Michael Fassbenders delivers a horse tip in space: “Breathe in the nostrils of a horse and he’ll be yours for life.” Perry Ogden, a filmmaker himself, spent two years in the mid 1990s at the Smithfield Horse Fair in Dublin (which takes place the first Sunday every month) to photograph the boys head-to-head with their animals. These intimate pictures, taken against a white background, have something of the mood from The Selfish Giant (2013) with Arbor and Swifty and the horse. When Ogden’s book Pony Kids was released in 1999, he told The Irish Times (February 6) that he was sure “that my early wish for a pony had something to do with my interest in Dublin’s pony kids. And the mixture of cultures. The global culture of Nike and Adidas sportswear, which all the kids were wearing, meeting this local culture of keeping ponies and horses in your backyard.”

Yann Arthus-Bertrand is a French artist and director of nature documentaries who also originated the bestseller The Earth from the Air (which has sold in 2.5 million copies) with those picturesque images from a hot air balloon. “Arthus-Bertrand was the first to photograph pets with the attention devoted to top models,” writes Lara Marlowe in The Irish Times (April 23, 2005), referring to his spiffy photographs of farm animals and their owners at the annual Salon d’Agriculture in Paris. But his most interesting work is found in his book Horses from 2014. Here he creates a kind of indoor situation with his rusty outdoor backdrop for his photographs of people truly wanting to show off their great affluence with their horses – remember the episodes from The Sopranos centred around “Whoever Did This” (2002) with Paulie Gaultieri’s alteration of the painting of Tony Soprano and the racehorse Pie-O-My? Their owners can think whatever they want, but the stars in these pictures are the horses.

Like so many others in Like a Horse, Jill Greenberg is not just crazy about horses but perhaps even more so about the idea and the reality of the sexual control over this powerful yet submissive force. “The horse project is not only a homage to the physique of these sexy beasts but also an exploration of the paradoxical gender identities cast into this unique animal. We see them as masculine, strong, muscular, even phallic. Yet they have been made subservient, so their position in the world relates to the role women continue to occupy,” she argues. “Their heads are remarkably phallic, and I have chosen to exploit this in my photographs. I have long been concerned with ‘exposing the phallus’ in a playful, mocking way. The horse’s neck is presented as confrontational image.” Sorry, but this is like listening to a woman with a purple or blue or green hair colour doing karaoke to “(I Want) Muscles”. So she is tantalising male energies yet lusting for them in the “sexy” (subjugated) Black Stallion?

What Greenberg brings out with expertise, flashes and Photoshop is an absolutely fantastic art aligned with the complicated punch of commercial photography, a mismatch that matches very well. (The ones that Mörner has selected for the show are as libidinal as the Pirelli calendars in the age before political correctness.) She seems to have a grip on the anatomy of the horse, much like the famous horse painter George Stubbs who based his laboured works on his eighteen months in an English country barn near Hull where he dismembered horses for what would result in the publication of The Anatomy of the Horse in 1766. Greenberg has actually nourished the idea to erect a full-size statue to commemorate the memory of Emily Wilding Davidson, a suffragette who walked right into the track at the Epsom Derby in 1913, as the rumble was approaching, to attach a Votes for Women scarf on one of the galloping racehorses – without the slightest consideration for the life and safety of the horses and their jockeys – and who had a fatal bang with King George V’s horse Anmer: “In that one visceral moment, the idea of the horse and the idea of feminism manifested itself for posterity, in a woman’s failed effort to halt the forward motion of the animal of the most powerful man in the land.” Shall we move on?

Thus begins Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse (2011): “In Turin on January 3, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the door of via Carlo Alberto 6, perhaps to take a stroll, perhaps to go by the post office to collect his mail. Not far from him, or indeed very far removed from him, a cabman is having trouble with his stubborn horse [at piazza Carignano]. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the cabman – Guiseppe? Carlo? Ettore? – loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and that puts an end to the brutal scene of the cabman, who by this time is foaming with rage. The solidly built and full-moustached Nietzsche suddenly jumps up to the cab and throws his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His neighbour takes him home, where he lies still and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words: ‘Mutter, ich bin dumm,’ [Mother, I am foolish] and lives for another ten years, gentle and demented, in the care of his mother and sisters. Of the horse, we know nothing.”

Alexandra Vogt’s horses – from her book The Dim Feet of White-Maned Desires (2005) – are wounded and uncared-for creatures in weird and gloomy but highly interesting settings in which she plays a girl who never read My Friend Flicka as a child, and who only seems to manifest herself as a sad memory, uncharged, unable to connect. In Sleek magazine (issue 26), Annika von Taube talks about “The moment in which the thought of hurting the horse doesn’t hold the girl back, but rather pushes her forward. The moment in which she begins to feel powerful, for mean reasons, but it doesn’t matter, because she’s good at making herself believe that these beings are much bigger and stronger than her.” Still, Vogt’s “dysfunctional” series of the eerie girl and her dirty horses is like John Lydon’s “This is Not a Love Song”. Of course it is, only a very different one.

“There is something about the outside of a horse that is good for the inside of man” was something that Churchill never spoke. “Early on [horses] taught me to be articulate, assertive and to believe in myself. These are not self-evident characteristics for anyone, especially for a young girl. They also taught me to be empathic, to understand how strong our body language is and to become aware of which signals I send and to be more attentive and sensitive in interpreting theirs,” writes the Swedish elite rider Lisen Bratt Fredricson on the other wall text in the show (which is also in the book); again with that trite saying that life is so much harder for women and girls, again that female chauvinist bromide about masculine glamour and taming this sexy beast between your thighs: “I think of their fantastic, long necks, the rounding of the of the muscles over their backs and buttocks, their large dark eyes and their silky-smooth muzzles. And what I find truly fascinating is the relationship between humans and horses. With its enormous strength the horse could have very easily ignored the will of humans, but we succeeded in taming it. And the horse allowed itself to be tamed.”

Kathleen Herbert’s Stable (2007) is the video work to watch in Like a Horse. In this eight-minute film (shot on 16mm), we hear the clip-clop of hooves and observe the doings of three horses, as through a surveillance monitor, as they spend a night in Gloucester Cathedral. The history behind the piece – with Lord Leven and his anti-Royalist army using the Cathedral as a stable during the English Civil War in the mid 1600s – is good to know but the piece carries itself beautifully in a chimerical dream state. Charlotte Dumas, who presented her book Work Horse in 2015, is from the Netherlands and her horses in the Anima series (2012) are the living residents of Arlington National Cemetery in Washington DC. Their task is to be graceful and to pull the caissons (that were once for the cannons) with the caskets of casualties from US battlegrounds. Makes me think of the skipper’s words to the boy who will die on the Moonstone vessel in Christopher Nolan’s tremendous Dunkirk (2017): “There is no hiding from this, son.”

Anima is the feminine energy in the male, but in portraying these reposed, elegant animals in a near state of sleep, Dumas seems to have focused on “the gap between wakefulness and slumber, a space for dreaming and reverie”. “Animals are at the outer end of our emotional experience […] we need them and use them to catalyse this emotional response,” she told John Mahoney in American Photo (January 8, 2013): “As it evolved it became much more apparent what it really meant to me to photograph these animals, because of course, they are portraits of animals, but they’re really about us. It’s all about our relationship with animals, and also symbolically the relationship between our species, with the human species being very solitary in this world and needing the animals, basically. And it’s about the diminishing existence of animals in our daily life.”

The eight pictures from Hans Silvester’s Fighting Stallions in the Camargue series (1974) bring on the frisky, dancing, almost wild horses, relieved of human obligations. He spent five years with these white animals in the wetland of Camargue and gained their trust with his camera. Silvester was quite an early practitioner of modern equine photography and his book The Horses of Camargue came out in 1976. “Like humans, horses in a band are notorious squabblers. Also like humans, band members fail to thrive without friends and family,” explains Wendy Williams in The Horse: The Epic History of Our Noble Companion, comparing the spectacles in those bands to a Shakespearean drama: “When you watch wild horses and you know their life histories, it’s like following a soap opera. There’s a constant undercurrent of arguing, of jockeying for position and power, of battling over personal space, of loyalty and betrayal. The show never lets up. Alliances are made and broken. Underlings often defy power. Sometimes a horse’s great patience is rewarded and he gets what he wants. Sometimes it isn’t and he doesn’t.”

Leland Stanford was a business magnate and politician who engaged Eadweard Muybridge in 1872 (after Muybridge had just murdered a man) to burn vast sums of money to develop a clever system for motion photography, primarily to prove that a horse is airborne during each stride of the gallop. Muybridge originated a string of great inventions, which forwarded photography and later made motion pictures possible, like fast emulsions, ingenious shutter devices and the trip wires for the wager that was won on June 15, 1878. The three kinetic charts in the show are all from that year and it is always a delight to see his images again, especially the ones with the horses. When American artist Susan Rothenberg’s daughter was born in 1972, Rothenberg suddenly started with her great and many horse paintings loosely based on Muybridge’s sequenced animals. Some of these paintings look like the horsy foetus floating in black space in a series by Tim Flach called Equus (2008).

There are two series by Flach in the show: nine pictures of horses in different headgear that at a first may appear as ceremonial display, but these are mostly protection gear against human conflict such as gas attacks and riots – and then the fascinating Equus (also a book in 2008) in which the embryo sprouts to a foetus and the foetus to a foal. This is colour photography in black and white. These are not the psychedelic 2001-wombs of Lennart Nilsson’s but the magic of life in a purer essence. “I am in awe of nature, but while my subject may be an animal, at the same time I am exploring things to do with what it is to be human,” Flach told the Photoshop website (no date):

“I am aware that the viewer may have already seen a subject intensely and that others have covered it. Part of my challenge is to de-familiarise the subject. I need to make people see the world as a little strange again, with fresh eyes and new insight. Perhaps I do animals as I do because I see so many people shooting wildlife images, going about documentary work with a subject. I am more interested in how we, humans, are involved in this subject: how we are anthropocentric, inevitably putting ourselves at the centre of any understanding of animals. We also respond to them by imposing our behaviours on theirs, and see them as we see ourselves.”

Life magazine photographer Peter Stackpole is famous for his vertiginous photography from the bridge constructions around San Francisco Bay in the 1930s. His mighty exciting pictures in Like a Horse from Atlantic City’s Steel Pier, which was a much bigger thing then, induce another kind of dizziness. They are all from July 1, 1953 and feature a horse and its female rider that fly into a pool of water from a jump tower as tall as twelve to eighteen metres (compare this to the highest plateau on a diving platform which is ten metres). On the ramp there was no way of turning, but according to the greatest name in horse jumping the horses just loved to fly. Her name was Sonora Webster and she was “Blind Venus” to her adoring fans after an accident in 1931 when she smashed her face into the surface of the water, but still went on for another decade despite her handicap. Most of Stackpole’s work was lost in a house fire in 1991, but his wingless Pegasus soars with unflagging resolve.

Completely unnecessary in the show are the really big names and the ones included for readers of Vanity Fair. The picture by Guy Bourdin (if I ever dare to mention his name again) has been on show before at Fotografiska, and Helmut Newton’s little Saddle, Paris (1976) is mostly a variant of the stronger Saddle I (1976) that was in the Newton show and which depicts Gunilla Bergström as a superb cowgirl tacked up with a saddle; in a black bra, cream jodhpurs and riding boots – a ponyplay on a bed at the Lancaster hotel in Paris – and she is looking like a human turtle, uniting Heaven and Earth in a way that sex should be like all the time. Newton explained that “I’ve always liked the idea of cowboys – the way they look, the way they walk, especially in the movies. Why? A cowboy stands in a certain way. He’s got a gun here, a gun there, his hands are always ready to draw. So I make the girls into cowgirls – with their hands ready to reach for the guns.”

There are works by David LaChapelle (featuring a Hollywood celeb) and there are works by the overexposed Martin Parr (British horseracing as a spiritual desert in high-pitched colours) and the true nadir of Herb Ritts (Calvin Klein, a video and a Hollywood celeb). Who in the right mind would care for another picture by Herb Ritts? It would have been great to see Richard Prince’s Cowboys (late 1980s) with the “appropriated” Marlboro Men roaming the West included in Like a Horse. Richard Prince danced to the music of time but his fake cowboys – they started to die one by one from lung cancer – ride into the sunset of eternity.

“Historians have largely neglected the tremendous influence of the horse, economically as well as culturally, in agriculture, transport, sport, and war, as a companion to humans, a cause of accidents, a prime mover of machines, a source of food, and, of course, a shaper of cities,” write Clay McShane and Joel Tarr in The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the 19th Century. Martha Camarillo photographed her Fletcher Street series in 2003–04 – a book with the same title was released in 2007 – on this street (which is only a few hundred metres long) in central Philly with its eight horses and the young black males doting on them. “They have been here for years, when the African American community thrived in Philadelphia, before drugs and unemployment steadily encompassed healthy neighbourhoods and they disintegrated into urban war zones,” Camarillo explains. “Despite it all, the horses have stayed, and they have because of the small, passionate, dedicated group of men determined to reclaim their neighbourhood and their children. In this fight, they use the one thing they know, love and trust, the horses.”

In The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, David Anthony describes how the first signs of the domestication of the horse became visible in the Pontic-Caspian steppeland after 4800 BCE: “What was the incentive to tame wild horses if people already had cattle and sheep? Was it for transportation? Almost certainly not,” he argues. “Horses were large, powerful, aggressive animals more inclined to flee or fight than carry a human. Riding probably developed only after horses were already familiar as domesticated animals that could be controlled. The initial incentive probably was the desire for a cheap source of winter meat.”

A favourite picture in Like a Horse is Beni Bischof’s old and new Bowcoy (2011) where the heads of the horse and the cowboy in John Grabill’s 1888 photo from the Wild West have switched bodies. Bischof works with all sorts of hybrid combos, like in The Last Unicorn (2013) with a human finger horn drilled through the picture of a white fairy tale horse. His numbskullery is too silly to be Dada but too great to be Mad magazine, or as the Swiss artist puts it himself: “I have a darker side. It’s very important for me. The jazzy expression is only the tip of the iceberg. The nice look is the Trojan horse that gets into the viewers’ brain to unfold its real essence. An important motivation for making art is to channel my anger over specific stupid facts on Earth.”

“So the horse occupies a peculiar and privileged position, not quite a pet, no longer a working animal, rooted, for many people in the past, but flourishing in the present,” reflects Michael Korda in his book Horse People: Scenes from the Riding Life. Bianca Pilet’s Falabella baby horse is portrayed as a baby pet doing baby pet things, like faire pipi on the bath rug. “The hair work on each horse was about four to five hours. The horse absolutely adored having been groomed and being played with,” says Julian Wolkenstein from Australia in the F Stop online magazine (no date) about his super-styled horses for real-life Barbies from the Pony Pin-Ups series (2007). “I thought that a painterly, classical rendition of the horse was a little bit more serious and it was a better way to get the humour across, rather than going with a light, fluffy, oversaturated look.”

Horses in art were really only out of fashion during the millennia of hardcore Christianity. Wendy Williams argues in her book that we have lost the art of observing these animals: “We see what the horse is doing, but we don’t always know why he’s doing it. We know little about how horses really behave when they are out of sight. We see horses in our barns and pastures and mistakenly assume that we see the essence of the ‘horse’. I’ve always thought this rather strange.” Look at the exquisite Vogelherd Horse, a less than five-centimetre-long sculpture in mammoth ivory carved 35,000 years ago, or at the over one-hundred-metre-long Uffington White Horse in the UK. Here it is – the entity of the horse.

“Horses are the stars of Ice Age art,” she writes and muses on that Ice Age artists must have spent “months and years just watching. They understood horses’ facial expressions, how their nostrils flared when they were frightened, how their ears betrayed their inner emotions, how they sometimes stood together in small bands, and how, sometimes, they would wander alone and seem rather forlorn. From this art, we know that before horses became our tools, long before the bit and the bridle were invented, Homo sapiens adored watching wild horses.”

I adore watching Erika Larsen’s People of the Horse (2011–12), perhaps the greatest joy and surprise in the show. “I believe I am searching for a moment of silence between myself and whatever it is I am photographing,” she says. The series is about the horse in Native American culture, and the six super-sharp and beautifully composed pictures at Fotografiska embrace both conceptual art and the language of National Geographic. They are splendid.

John Wood describes the final destination for the protagonist in Gulliver’s Travels from 1726 in the foreword to Ezekiel’s Horse – how Lemuel G “encountered two vastly kinds of creatures: the Houyhnhnms, those intelligent, wise, gentle, truthful, reasonable, and beautiful horses who were in control of the society; and the Yahoos, a savage, cruel, deceitful, unreasonable, ugly species that looked frighteningly familiar. They murdered, raped, fought, stole from one another, and, but for being a bit more hairy, looked like us. They could not speak, but apart from that, they were the frightening mirror of ourselves. Gulliver was understandably repulsed; and during his stay tried to model himself as closely as possible on the kindly and noble Houyhnhnms. When he asked his teacher the meaning of that strange word Houyhnhnm, he was told it ‘signifies a Horse’, but means ‘the Perfection of Nature’.”

This is naturally the Disney version of what Jonathan Swift intended with the story about these sordid elitists, how they owned the discourse and yet were unable to examine their own behaviour. “The notions that life here and now is worth living, or that it could be made worth living, or that it must be sanctified for some future good, are all absent,” as George Orwell wrote in his essay “Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver’s Travels” in Polemic magazine (September/October, 1946): “There is something queerly familiar in the atmosphere of these chapters, because, mixed up with much fooling, there is a perception that one of the aims of totalitarianism is not merely to make sure that people will think the right thoughts, but actually to make them less conscious […] The Houyhnhnms, we are told, were unanimous on almost all subjects. The only question they ever discussed was how to deal with the Yahoos. Otherwise there was no room for disagreement among them, because the truth is always either self-evident, or else it is undiscoverable and unimportant.”

Three hundred years into the future in Houyhnhnmland, and our hope is complex societies that create the art we see in Like a Horse.

Tintin Törncrantz

Tintin Törncrantz is an author specialized in photography. He lives and works in Stockholm, Sweden.

Like a Horse

Fotografiska

Stockholm, Sweden