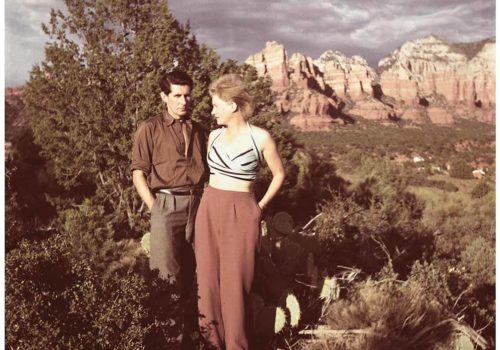

Primož Lampič, The Possibilities of Revolt: On Lee Miller’s Photography

Lee Miller is a fascinating character of contemporary photography. Recently, her son Antony Penrose – Director of Lee Miller Archives – gave an interview to the historian Primož Lampič. We decided to publish it. Interview by e-mail between December 2010 and September 2011.

Primož Lampič: How many negatives does the Lee Miller’s opus contain?

Antony Penrose: We have in the Lee Miller Archives about 60,000 negatives – mostly 55 x 55 m/m from her Rolleiflex but there are about 5,000 half plate and full plate from the Vogue Studio days, and about 5,000 frames of 35 m/m. This clearly does not represent her total output of work. It is hard to know how many negatives are missing. We have only a few – about 50 – from the New York Studio and only a very small number – less than 30 from the Paris Studio.

We also know she destroyed a substantial amount of negatives from the Concentration Camps after the war, and others were lost or damaged. In all I would estimate our total holding of her work to be in the region of 80,000 vintage prints and negatives.

P.L: Does the selection of Miller’s photographs presented in various exhibitions contain only her vintage prints?

A.P: Mostly we present Lee’s work as modern gelatine silver prints made from the original negatives in house by our fine printer and curator Carole Callow. This was the basis of the Ljubljana show. Lately we have been making digital images as they are cheaper and with Photoshop we can repair damage and use negatives which would have been impossible to re-touch in the normal way. We rarely send out vintage prints to a show, the exception being top international shows like the centenary curated by Mark Haworth-Booth at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. This is because the vintage prints are old, precious and fragile.

P.L: Do you select photographs to be reproduced for exhibitions from the list of vintage prints or you choose freely among all Miller’s negatives preserved?

A.P: It depends on the show. Some exhibitions – only a few – demand vintage prints where possible, but since we have few vintage prints we mainly choose from all negatives and available sources – sometimes we don’t have negatives so we copy prints.

P.L: Which criteria do you use to select photographs among negatives that Miller never printed and were never published during her life?

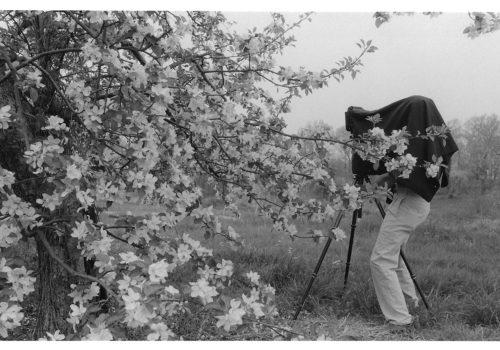

A.P: It depends why we are selecting the photos. If we are telling a story – maybe illustrating words that Lee herself wrote or setting picture in a biographical or historical context we use the image that shows the event the best, given the usual considerations for composition and technical perfection. As you will understand, sometimes in journalistic work the content of the image can over-ride many other considerations. Although we prefer to publish the images un-cropped, there are times when we do crop the image to make the information clearer.

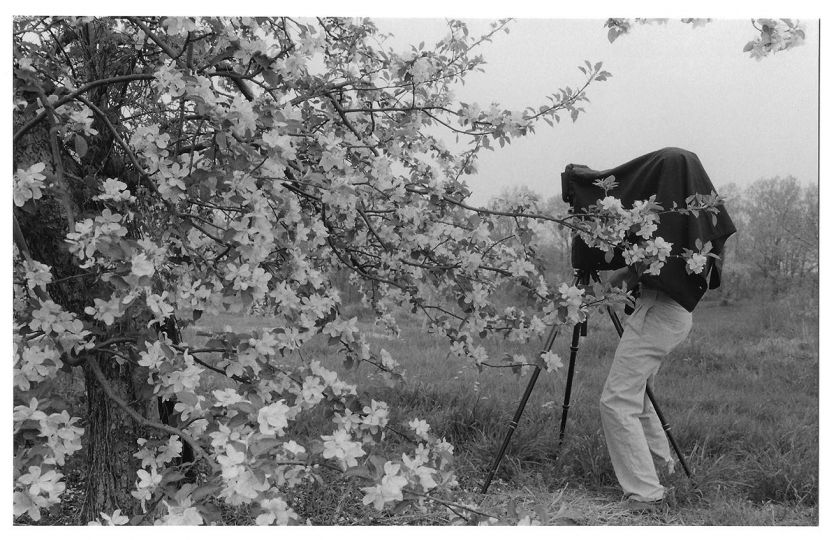

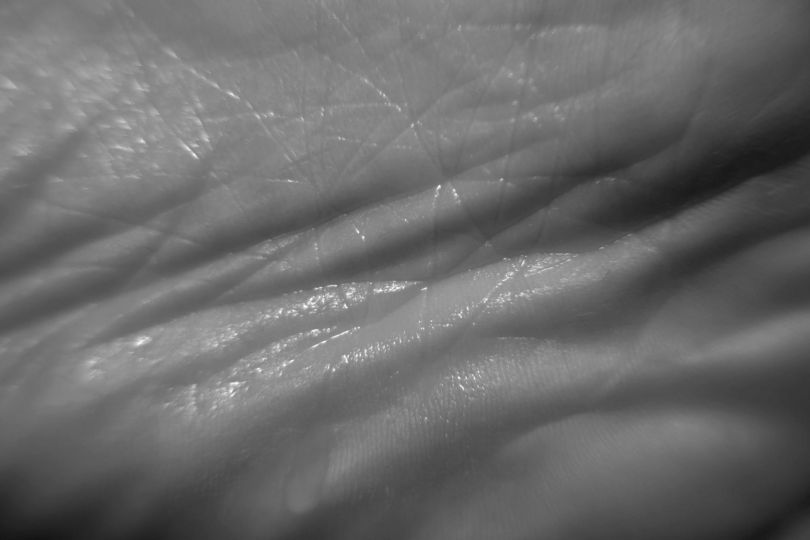

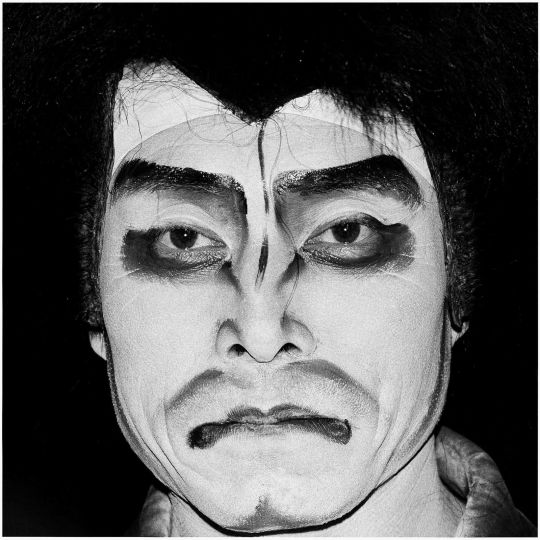

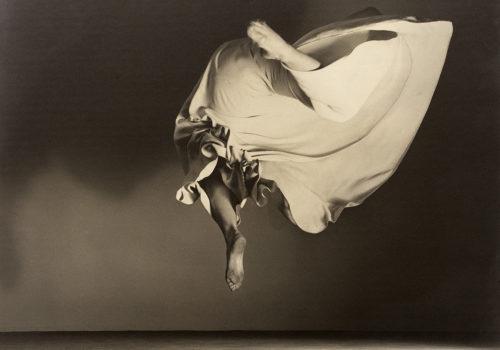

If on the other hand we are selecting images to show Lee Miller’s unique way of seeing – her Surrealist eye if you like – then we have to be guided by the images she produced that we know she like and approved of. There are few of these, but over the years I believe I have had the opportunity to examine all the significant images from her Paris and Egypt period where the surrealist eye was at its most evident and this helps make me aware of other images of this genre which are unpublished. We print these images un-cropped and with a tonality we feel to be as close as we can get to that which we believe Lee Miller intended.

P.L: Do you select alone or do you have advisors and curators to help you?

A.P: It depends on the purpose – sometimes I select alone to choose a body of work that will eventually be taken on by a curator or editor. When I am working with a curator or an editor they have a specific theme in mind for their book or exhibition and I become an advisor with a degree of influence that varies according to the experience of the curator. The top ones need little input, others need a lot of help. It varies, and I like working with strong and experienced curators because they bring new understandings to the work.

P.L: So Lee Miller as we know today is a product of a kind of collective authorship. Would Miller like this deconstructivistic approach to her work?

A.P:With regard to the Surrealist work Lee was surprisingly unconcerned as to how it was used – in common with other surrealist artists, particularly at the beginning of the movement, I think she felt that once a work had been made it should in a way determine its own destiny. She also made her own changes – the abstract landscape photograph ‘Impasse a deux anges’ is signed by her as both a portrait format and a landscape. We avoid cropping or changing these surrealist works as I feel this would have been her preference.

In her photojournalism for Vogue as distinct from her work in Egypt and Romania, she was aware she was shooting for an editor, who was the client and had a layout designer who was free to crop and or manipulate the photograph however required. You will find a lot of her work from this period is shot wide to give good cropping options. Clearly she wanted her pictures to look their best and relied on others to do this in the layouts. Consequently I feel she would have approved of the cropping we sometimes do to make the picture more ‘comfortable’ in its space.

P.L: I’ve understood that Miller didn’t talk much about her work. Is there in any collection of Miller’s written statements concerning her photography, attitude toward the medium in general etc.?

A.P: Beyond a few lines here and there Lee never made any comments about her photography that we have found – just a few comments about how she got angry with bystanders in Munich who thought they were being helpful when they told her she should not take pictures looking towards the sun.

P.L: Which part of Miller’s work, in your opinion, represents her major contribution to the world photography?

A.P:Probably her Surrealist work and the way that her surrealist eye and her surrealist mind-set informed her work in fashion and reportage. This is what made her unique.

P.L: You think that these shots were the most important for Miller as an author and as a person, too?

A.P:Yes, not so much a specific image, but a genre of images – a style that demonstrates she was a Surrealist. As a person this was important to her because the surrealists had a huge commitment to Peace, Freedom and Justice – you will see this as the underscore of her work. As an artist it was about finding the metaphor and the connections that lie beneath the surface – the axiom of ‘Nothing is as it seems’ was part of her way of seeing.

P.L: I notice that Miller ceased to photograph in surrealistic way after the WW II. Am I right?

A.P: I would not say she stopped altogether – her wit is still evident in some of her images – usually the more casual ones around Farley Farm, and it is true her fashion and portraiture is a little more formalised than before. The spark was still there but I feel that the awful effects of post traumatic stress dulled her creative spirit.

P.L: Surrealistic photography was mainly about things, bizarre, referring to human figure and mind, but nevertheless things. Even human figure was photographed as a thing, avoiding to a certain degree realistic outlook and portrait resemblance. After the war Miller mainly took pictures of men and women, very simple in comparison with a surrealistic mood. Do you agree?

A.P: Yes I think that is a good observation as her pictures became more influenced by the needs of photojournalism.

P.L: A War photoreporter has to make an eloquent, communicative image, of course, but I think that Miller’s experience of war influenced her afterwar work from other aspect. The surrealism as an art style was a play. As much as it was engaged theoretically, it was detached from life. The war on the other side was real, and unveiled life at it’s lowest, basic strata. I think the art made a hard landing in reality the in years 1941—1945. Miller was aware of that and at the same time she was a victim of that crash. Her prewar concepts of art were damaged as much as her concept of life. Would you agree with that?

A.P: It is interesting to explore the position of art in war and in Lee’s life at that time. The underlying drive in Lee Miller’s life was the importance of peace, freedom, honesty and justice. Before the war Surrealism gave her a means of expressing her passions as a cause. In wartime being a photojournalist answered the same need. They were different means to the same end, different ways of expressing her passion for the same conviction. An in terms of expression there are times when she realised that clarity and directness were needed above all to carry the message, and photojournalism was a way of conveying the information she wanted to impart.

If you want to explore what I believe to be the root of her drive, look at her experience of trauma as a child and the sense of in-justice that it must have engendered, and then recall that one of her most formative experiences was being sent to a Quaker school. Quakers hold the values of peace, freedom, honesty and justice as core values.

Art was something she returned to – I don’t see art in her case as being damaged by the war, just temporarily put aside in favour of photojournalism, a more direct way of communicating that suited the moment.

I don’t think Lee broke faith with her pre war concepts or art – I think she held true to them. What changed were the circumstances of her life and her disillusionment was not with the art but with the hopes she had held for the brave new world that would follow the war. I see this because although she was not so much a practitioner in the public arena in the post war years, she remained firmly committed to art and the importance it has in changing the world – or at least in informing the way people see. This is demonstrated in the fact she continued to photograph – but her subjects were mainly the artists Roland Penrose was writing about – Picasso, Miró and Tàpies. She also invented her own unique art form of surrealist cooking and that occupied her right up to her death. In fact we have just discovered the manuscript of a book about her cooking she was writing when she died. So I think the genre of her work changed, but the principles she held did not.

P.L: I was looking Miller’s afterwar work in the contest of Theodor Adorno’s words from 1951: »There can be no poetry after Auschwitz.« I feel the same reconsideration in Miller’s work. I find it much more serious, dedicated to her friends, in a way trying to preserve them symbolically with the photography. In the contrast with it, surrealism was humorous and poetic in its own way. I think Miller considered it unappropriate to continue after her bitter war experiences. It may not be a conscious reaction, but an emotional one. The world was simply not the same as before the war. Would you agree?

A.P: I don’t agree that Lee Miller felt Surrealism was inappropriate in the post war years – on the contrary it remained a reason for living and emerged in her cooking and in her understanding of the modern artists and fellow surrealists who surrounded her. I have not met many holocaust survivors, but one thing I notice they have in common was the determination to retain the memory of the facts and the experience but at the same time to keep moving forward. It would not have been helpful to anyone if there was never again any poetry. Poetry may have seemed justifiably irrelevant to Adorno in 1951 but I notice some significant people who were part of the holocaust reaffirmed the purpose of their lives by moving on with tremendous creativity. Victor Frankel, Bruno Bettelheim and Primo Levi did not write poetry but their words are so vital they move us just the same. Lee Miller did a similar thing. It took her 20 years to get her life under control, but even during the time of her greatest torment she still photographed, and then she re-invented herself as a gourmet cook. I don’t think that is a life entirely without poetry.

P.L: Miller was in contact with Vogue first as a model then as a writer and photographer. How did she get along with Vogue’s editors as an author?

A.P:Lee Miller got along very well with Vogue editors as an author. To start with she was rather shy about writing, and the manuscript of her first piece on Ed Murrow was full of false starts and distractions, but it was well received and successful. One of the things that prompted her to write was that she was very dissatisfied with the text provided by the staff writer Lesley Blanche. If you look at Blanche’s work is it rather formulaic and insipid, and I can see why it did not appeal to Lee. Audrey Wither’s, Vogue’s editor told me in an interview that she was deeply impressed with Lee’s dispatches from Europe. She said it was a wonderful surprise to find that Lee was such a talented writer who sustained an amazing output of stories that were so consistently well written and informative. She told me that her main regret was that they due to paper rationing she did not have enough space to print as much of Lee’s work as she would have liked. Audrey Withers remained a good friend of Lee’s until Lee died, and when I interviewed her and heard her speak publicly it was still evident how much she had liked and admired Lee.

I don’t have a direct comment from the US editors of Vogue, but clearly they printed the work at length, sometimes using more images that British Vogue, as the picture-led story like in LIFE Magazine was more their style.

P.L: Miller was a part of surrealistic group and many of the surrealists were this or that way involved in politics, Breton, Picasso beeing communists for a short time etc. In addtion, surrealists as a group are considered today as an avantguard group, having ambitions, with their activities not only to produce pieces of art, but of changing the bourgeois society as a whole. With them art had a function. Did Miller ever talk about politics in the way the surrealist should have talked about it?

A.P: Lee Miller did not talk politics in the way most people do but it was obvious where her inclinations lay from her conversation. She was not a supporter of any political party believing them to all be corrupt and the more ideological and the more totalitarian they were the more cynical she was about them. Stalin for her was on par with Hitler. The Surrealist values of Peace, Freedom and Justice were of great importance to her. She valued democracy as the ‘least worst’ of the systems, but would probably have preferred anarchy.

P.L: Vogue was a typical bourgeois magazine reporting on fashion, glamour, high society and similar. How did Miller accept that rich world, but at the same time have many good friends among revolutionists?

A.P: In just the same way as Rene Magritte dressed as a banker to disguise himself as a bourgeois, Lee, who was very familiar with high society assimilated with Vogue and used it as a vehicle to do the reporttage she really wanted – women at war and humble people doing extraordinary things before D Day and then personal, passionate and close stories of the conflict and how it affected her French friends, the GIs and the European civilians. She was clever enough to get a couture magazine to become a voice for the ordinary people for a brief but critical period of 18 months in world history.

We have exchanged so much that there is a danger of going back over the same ground, but in conclusion I would like to tell you what it is that keeps me motivated to work on my parents material.

The art and the beauty of Lee Miller’s work is of course compelling. Both my parents had unique forms of expression and just from the aesthetic aspects there is much to delight and satisfy. But for me the aesthetic and the intellectual side of this, no matter how fascinating, is not enough in itself. What drives me forward, and compels me to go way beyond the limits of fatigue, finance and comfort is a much bigger thing. It is that the work tells us about the eternal importance of peace, freedom, justice and love. That is what was important to them in their times, and it remains important to us now. They stood against oppression and constantly championed freedom. Some of Lee’s war and holocaust images documented one of the darkest periods of the history of mankind, and through these images my parents continue to work today, making their contribution to the creation of a better world. They set us standards to aspire to, and dreams to inspire us. I am privileged to work with their materials and have the inspiration of their ideals in my life, and it gives me pleasure to share their art and their lives with others.

P.L: Dear Mr. Penrose, thank you very much.