Two weeks after the Yangon Photo Festival had ended, my head was still swimming with images; but what really stuck in my mind from this year’s edition was the perseverance of the Burmese photography team.

In a country like Burma where it is still very difficult to organize any event in a public space, and where bureaucracy remains largely under military control, the YPF team had to hold its breath until the very last minute. Despite the support of the new regional and municipal governments, disaster seemed to loom on the horizon. The whole event could have been cancelled. But then, as the first images were being projected onto the giant screen in the Maha Bandula Park, the tension was suddenly released and the exhilarated crowd broke out in laughter, tears, and cries of joy. This outburst of emotion on the part of a population still unaccustomed to this type of event made months of hard work completely worthwhile.

Christophe Loviny, director of the YPF, succinctly captured the mood of that opening night: “It was a struggle to get there.” It was indeed their fighting spirit that gave the YPF its unique strength. For nine years now, the YPF has turned to the power of images and photo-stories to draw attention to major social and environmental issues faced by the country. There was not a single person attending the festival who would fail to grasp the importance of photography in writing a new chapter in the history of Burma (renamed Myanmar by the junta in 1989, while Rangoon became Yangon).

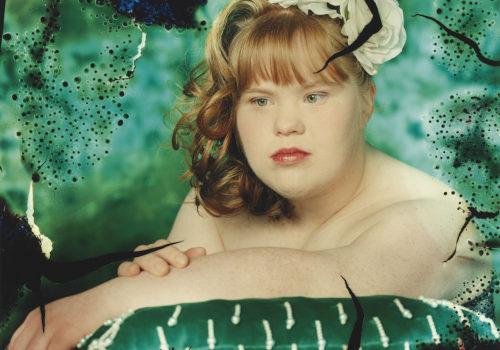

Mayco Naing, my wonderful hostess during the festival, remarkably exemplifies that spirit. She is today an important figure in contemporary Asian photography. Mayco rose to prominence when the universities had been shut down by the military and she got a job at a photo studio for 3000 kyats (about $3) a month. Having spotted an YPF poster in 2010, she attended her first master classes, received the Creative Prize, exhibited abroad (the Lyon Biennale, the Bangkok Biennale, festivals in Lishui and Dali in China), Mayco was finally able to have her first solo exhibition at home. Her portrait series, entitled Identity of Fear, captures the Zeitgeist of the Burmese generation born around the time of the 1988 revolution, raised with little education, conservative values, and coming of age under a repressive military regime.

Drawing on her newly-found freedom of expression and the desire to share her experience, Mayco hopes to be able to train as many citizen artists and photojournalists as possible, especially in regions where ethnic minorities are still facing armed conflicts. Her personal struggle resonates with many young Burmese photographers I’ve met, who, like Mayco, are no longer afraid to speak out.

Thus, on the occasion of the Yangon Photo Night, the young Kachin photographer Zinghtung Yawng Htang surprised everybody with his story Again, which openly criticized Aung San Suu Kyi seated in the front row. A rumble of astonishment rose from the crowd gathered at the Institut Français. The words on the giant screen spelled out: “Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the military cooperate with each other. They use violence and brutalize ethnic minorities.” As the festival was not self-censored, even when it came to its godmother, the State Councilor responded to the photo story with vigorous applause. This freedom of expression signals the beginning of a new era in the country.

The YPF has become a powerful media source for all communities, especially those most oppressed or marginalized, as well as an important voice in the debates and in the ongoing dialog in a fast-changing political context. Against the background of peace talks initiated by the new government, the overarching theme of the exhibitions this year was ethnic diversity. The 21st Century Panglong Conference aims to put an end to the armed conflicts tearing apart a country that is home to no fewer than 135 ethnic groups.

With the master class as its weapon of choice, the YPF may be proud to have attained its primary goal: training a new generation of Burmese photojournalists capable of speaking out for the disempowered. The YPF thus subscribes to the philosophy brilliantly summed up by Henri Cartier-Bresson, deliberately adopting a military metaphor: “To photograph: it is to put on the same line of sight the head, the eye and the heart.”

The YPF further spearheaded action by organizing meetings with major players in the world of photography, such as Dominic Nahr, a famous photo reporter; Laurens Korteweg, Director of Exhibitions at World Press Photo; Hossein Farmani, founder of the Lucie Awards (“the Oscars of photography”); as well as a number of other guests who use images as a lever for social progress and who helped build a momentum at the festival, putting it in the front lines of citizen photojournalism. In addition, for the young Burmese photographers, those meetings represent a veritable social capital, so valued by Bourdieu, and a non-negligible element of their personal success, professional opportunities, and their visibility on the international scene.

The festival can be proud of opening the eyes of an audience of 100,000 to previously neglected issues thanks to the work of Burmese and international photographers. I often wondered, during the screenings, what the reactions of the public would be if these photo essays were shown in Paris, in front of the Hôtel de Ville or in the Luxembourg Gardens, or at any symbolic site in any European capital. Having rape or pedophilia, open critique of the government, or child adoption by a homosexual couple, treated on a giant screen would likely provoke aggression on the part of conservative groups. In many respects, the YPF and the Burmese public have given us a lesson in transparency and universal tolerance.

Lastly, the YPF hopes to intervene in a wide open field of possibilities, that is in the classrooms. “On social networks, everyone expresses themselves nowadays through words as much as through images,” observed Christophe Loviny. “But the visual language is for the most part very rudimentary or infantile, limited to selfies and snapshots of food. The reason is quite simple: we spend years in school learning to write, but no one teaches the language of images.”

Thanks to its visionary thinking, the YPF takes the next step to include visual training in the curriculum in order to educate students in using images the way we use words.

Nowadays, anyone can become a photojournalist. Aung San Suu Kyi, by the way, said as much in a subtle remark. “We sometimes have a hard time distinguishing photo stories by professionals from those by emerging photographers,” she noted amicably, thus demonstrating that, with short and effective training, anyone may be capable of building a powerful story with images.

Nevertheless, most projects piloted in schools deal with photography as an art form. Photography, however, is also a pastime, a medium, and hence a language that includes all the aspects mentioned. Thanks to social networks, a message with a visual component will spread much faster than through traditional media. The festival’s new Facebook page, “Myanmar Stories,” embodies this effectiveness: every week, a newly published photo story reaches a massive audience, and the site has become a popular, quality media source.

Photography has become a universal language simply because it is accessible to all. Thanks to universal interpretation and diversity of understanding, photography possesses a real power to create change in a civilization where the image has become essential to communication.

Christophe Loviny’s message in a bottle is therefore this: he wants to participate in a web-based network of exchange with photographers, academics, pedagogues, and instructors in order to reflect on images as language—a basic, everyday language to be used by everyone. “This is the beginning of a story, and we are in the process of writing it,” he declared. The phenomenon is already there: we just need to give meaning to our smartphone screens.

Aline Deschamps

Aline Deschamps is a journalist, photographer, and a cultural project manager working in Paris and Bangkok.

9th Yangon Photography Festival

Yangon, Myanmar