The Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico is currently presenting a private collection, previously unseen, to which Pedro Slim himself a photographer has been adding for twenty years. These one hundred photographs or thereabouts by more than sixty big names including Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Diane Arbus, Bill Brandt, Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe, Man Ray, Francisco Toledo and David Wojnarowicz. In this column, photographer Chuck Samuels brings a point of view on the exhibition.

Earlier this year, Brian Paul Clamp, director of ClampArt in New York, informed me that one of my photographs (After Bellocq, 1991) had been acquired by Pedro Slim, a well-known Mexican photographer and collector, and that my photo would be included in a large group exhibition on the body entitled La parte la más bella / The Most Beautiful Part. Based on Slim’s collection. The show was to be curated by James Oles and presented at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City in from October 19, 2017 to March 11, 2018. I also learned that the exhibition was to be accompanied by a catalogue and that it would be an integral constituent of the 2017 edition of FotoMÉXICO, a major international biennale of contemporary photography organized by Centro de l’Imagen, in Mexico City. I decided to attend the opening and my trip was supported by a travel grant from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec.

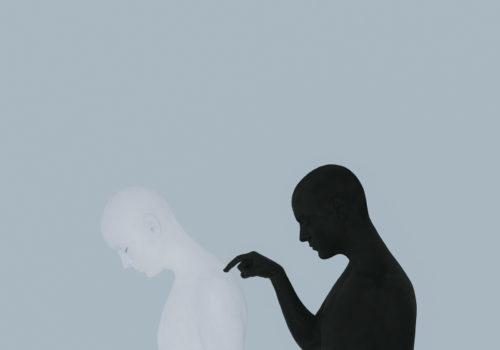

A few days before the opening, I met with Pedro Slim in Mexico City and it was a real pleasure to spend the afternoon getting to know him, his work and his collection. Besides its foremost focus on the photographic portrayal of the human body, the collection is not uniform – in fact it is somatically polymorphistic. There is a clear predominance of male photographers and bodies represented in the exhibition, but female artists and figures play a smaller yet significant role. Similarly, while the gaze is often queer and many of the works frankly homoerotic, there are also numerous photographs that resist those definitions.

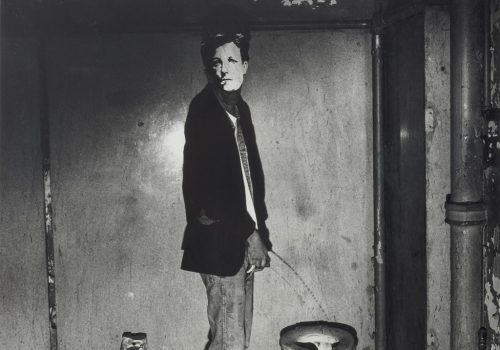

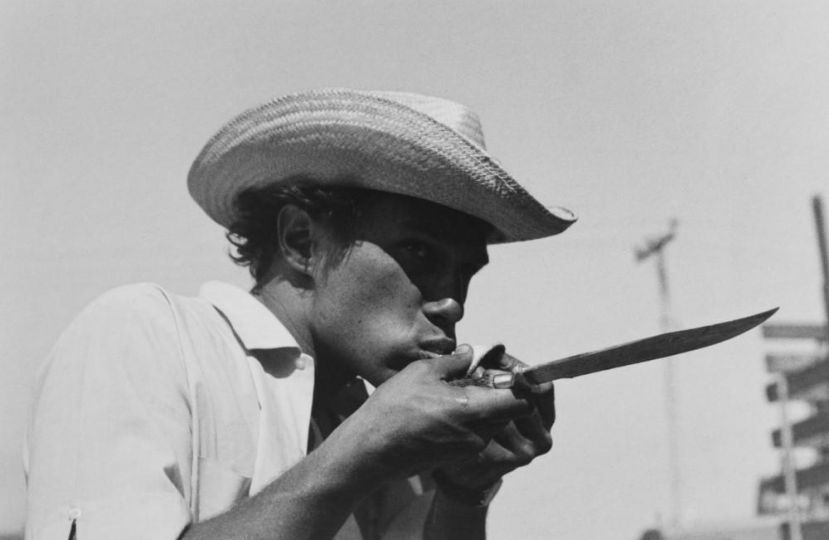

There are images of the body beautiful (in the modern Western sense) such as Lee Friedlander’s Nude, 1980 or Karlheinz Weinberger beefcake photos, or Greg Gorman’s Tony Ward, Bent Over but there are also less than “perfect” bodies on view, such as Antonio Reynoso’s La gorda from 1960 or Anthony Friedkin’s backstage portrait, Divine, Palace Theatre, San Francisco, 1972, or several of Joel-Peter Witkin’s harrowingly beautiful disfigured bodies, or images of acts of self-inflicted harm in works by Larry Clark and Amos Badertscher.

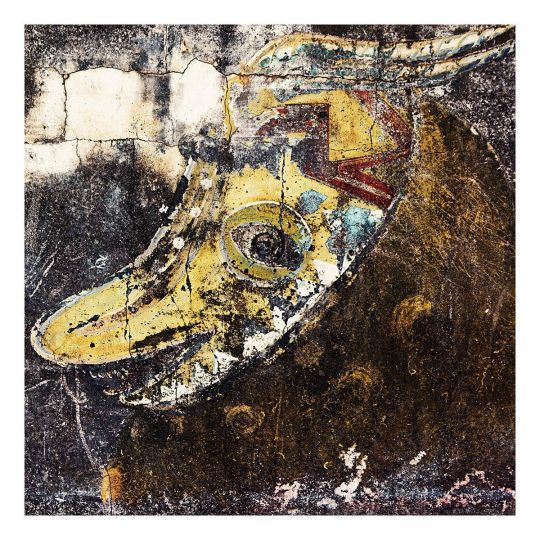

There are poetic works such as Man Ray’s La Retour à la raison from 1923, an image that finds its sibling in Edmund Teskes’s Richard Soakup, Los Angeles from 1944 – photographs that are in stark contrast to the unexpectedly touching street photographs by Arlene Gottfried from the 70s or documentary photos by Danny Lyon and Sabastião Salgado. At first glance, these street and documentary photographs seem perplexing inclusions, but after reflection one understands that they are essential elements in the fabric of the collection. In fact, there are a number of photographs that don’t even depict the human form at all but are tangibly linked to the body, such as Peter Hujar’s photographs of the Hudson River and the Woolworth Building, both taken from the perspective of the West Side piers, a New York gay cruising zone in the 70s. There are images with a very strong formalist bent including works by Bill Brandt, Eikoh Hosoe, Horst P. Horst, as well as Herb Ritts, and but also a number of conceptual pieces such as four prints from David Wojnarowicz’s series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79. We can find collages by Antonio Salazar and John O’Reilly as well a cluster of solarized images by artists such Konrad Cramer, Josef Ehm and Ferenc Berko.

At the entrance to the exhibition the visitor is greeted with James Oles’s introductory wall text and two inscribed photographs by Duane Michals: The Most Beautiful Part of a Man’s Body and The Most Beautiful Part of a Woman’s Body from 1986. These two works immediately introduce us to theme at hand and provide us with first example of a profusion of ways to perceive and to understand the body that are offered by the exhibition. In Michals’s case, the male body, particularly its abdomen, is the site of adult erotic desire while the female body, specifically her chest, is discussed more from the perspective of a regressing old man as a source of love, comfort and nourishment. Once past the entrance, we discover that the exhibition is installed on the walls of a large circular room painted a light gray as well as in a series of smaller open ended enclosures branching out from the center of the room, each one’s inner walls painted a carnal red-ochre.

Oles utilizes the continuous wall space of the periphery to sequence multiple groupings and to permit longer narratives to unfold. For example, on a long stretch of light-gray wall, he brings together three faceless bodies (David Salle’s Untitled, 1980-90, Kenneth Josephson’s Sally, 1976, and Helmut Newton’s California Fingernails from 1981) that are separated by a space from Diane Arbus’s Girl sitting on a bed with her shirt off, N.Y.C., 1968 that is, in turn, adjacent to a cluster of photographs linked to windows (Dirty Windows #1 and Dirty Windows #16 by Merry Alpern from 1994, two nudes by Manuel Álverez Bravo – Sin titulo, 1977 and Ana Maria DG, 1985 – followed by Roger Catherineau’s Untitled 1954 and ends with the aforementioned Man Ray in which a woman’s body is bathed in the mottled light passing through a rain-spattered window).

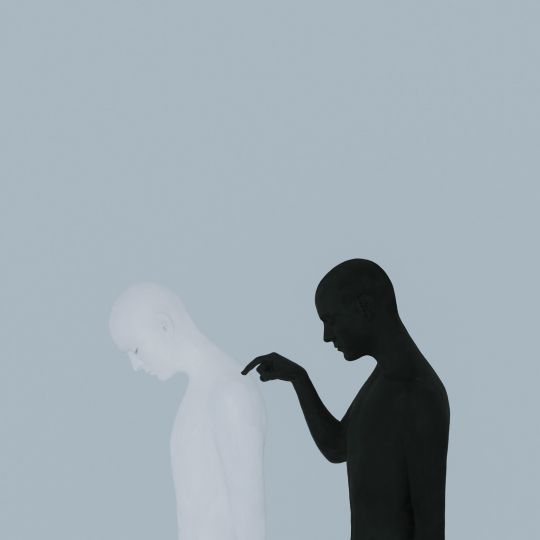

The smaller spaces – half-hexagons with their outer two walls reaching out invitingly to the spectators – radiate from the center of the room. These structures provide spaces for images in smaller and more intimate gatherings. For example, Oles uses one of these cloistered spaces to reflect on gender ambiguities. The sequence begins with three modestly sized images including a photograph of the artist Jesús Reyes Ferrreira, who presents himself adorned as Salome, made by Librado García (who signed as “Smarth”) entitled Salomé, ca. 1917, accompanied by Antonio Garduño’s Nahui Olín, ca. 1924 -27 and Pierre Molinier’s Ce qui est merveilleux, 1996. The second wall has comparatively larger prints including Arbus’s Naked man being a woman, N.Y.C., 1968 and two of Nan Goldin’s early works, Ivy with a fall, Boston and Bea as Greta Garbo on the day Steichen died, Boston, both from 1973. The third wall continues the grouping with two informal portraits by Anthony Friedkin (Michelle, Female Impersonator, C’est La Vie Club, North Hollywood and Divine, Palace Theater, San Francisco both from 1972) and concludes with Graciela Iturbide’s forthright portraits of Magnolia, a gender-fluid indigenous Muxe from Oxaca. Inhabiting a space between straight photography and surrealism, Iturbide’s images, entitled Magnolia I and Magnolia II from 1986, seem enigmatically unanchored in time and, ergo, they loop us back to Smarth’s Salomé.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, we find two examples from Pedro Slim’s own work, portraits from a long-term project entitled De la calle al estudio in which Slim brought various young men found hustling on the streets of Mexico City into his studio to be photographed. In Domingo and Rogelio, both from 1999, each man projects a persona that is tough, vulnerable and seductive. The decision to incorporate Slim’s images into the exhibition was not without risk, but the works serve to situate his own practice and his own obsessions within the context of the collection and, in the final analysis, his two photographs stand on their own.

It is a tribute to James Oles’s insightful, sensitive, and sometimes playful curating that these diverse photographs are assembled with both a profound respect for the original images and their initial contexts as well as for their relation to the exhibition as a whole.

The exhibition catalogue is a lushly illustrated and beautifully printed hardcover book with a striking pink binding. It contains an introductory text by Sylvia Navarrete, the Director of the Museo de Arte Moderno, who provides a frame of reference within the Mexican milieu for Pedro Slim’s own work and his collection. Also included is a comprehensive essay by James Oles, entitled Beautiful Parts, in which he reflects on the collection and comments on many of the issues it raises. He argues that the collection “reveals not only the elasticity of gender conventions over time, but the increasingly political use of photography to illuminate, undermine and problematize those conventions.” In addition to his essay, we find a series shorter texts by Oles with remarks of historical, technical, and/or anecdotal significance regarding each photograph. The catalogue closes with the words of Pedro Slim himself in an interview with Mexican gallerist and curator, Arturo Delgado.

In both the exhibition and publication the body subject to a multiplicity of approaches. At the very least, it is studied, desired, eroticized, abstracted, worshipped, pitied, loved, desecrated, glorified, parodied, stereotyped, and objectified. But there is a pathway, constructed by the choices made by Pedro Slim as he built the collection and further articulated by James Oles, that the viewer/reader can follow in order to reconsider the photographic representation of the human body in new and progressive ways.

The strength of the collection and the exhibition does not reside in any kind of formal or content oriented coherence, rather it issues from a singular, rigorous and deeply compassionate vision, one that maintains a firm grasp on the human body while simultaneously embracing the larger human experience – an experience that is both rich and mesmerizing in all its beauty, horror, hope and despair.

Chuck Samuels

Chuck Samuels is a visual artist who has been exhibiting his photographs since 1980. He frequently shoots self portraits, and his work tends to address memory, photography, and cinema as subject matter.

La parte más bella

From October 19, 2017 through March 11, 2018

Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City

11560 Miguel Hidalgo

Mexico City, Mexico