Here is the text published yesterday by David Burnett on his blog:

“Adios Amigo…Somewhere in the very late ‘60s, as a budding photojournalist, I began shooting color slide film. Ektachrome, Agfachrome, and Anscochrome were the top films, each processed in a procedure known as E2 (and which later evolved to the current day E6). The film could be turned around in about an hour. The actual mechanics and chemistry were relatively easy if you’d passed a chem lab class in high school, and I even souped a few rolls at the Colorado College Physics Dept. darkroom. But the color wasn’t really true to life, and there always seemed to be a bit of a flatness to it. Simply put, yes, you could shoot a color picture, but along the way you missed a lot of the subtleties of what you were seeing. Photography is really all about light, and how we see it. The way it illuminates a subject, wraps around it, or creates a sheen which gives a scene its personality. My first published color images were of the scene surrounding the launch of Apollo XI, the first mission to land men on the moon. I was living in Miami, and convinced Charlie Jackson (Time’s picture editor) to let me concentrate on the tourists and history buffs who came from all over the country, camped out in their VWs and Mercurys, and waited with excitement to witness the launch of America’s biggest rocket ever. I shot like crazy, along the way partnering up with my French colleague Jean-Pierre Laffont. We photographed the campers, the kids, the square dancers, the lovers on motor cycles, and in the next morning, the hundreds of folks in Titusville who shaded the sun from their eyes to watch the Saturn V rise up into the heavens. It was still the era when processing color film for magazines required several days. The process must seem antiquated by today’s “instant” standards, but involved shooting the pictures, shipping the film to the lab in NYC, having it processed and edited, then “engraved” (like scanning except oh so analogue!) to a plate, which was then used on the press to create the color image. Complicated, difficult, and full of potential technical snafus, but it did let you create a color picture. I was happy beyond belief that I was finally a “Time COLOR” photographer. Yet through it all, as I slowly started to get more assignments in color, I wasn’t very happy with the way the photographs looked. They were never really sharp. The color always had a kind of fogginess, a softness which made me wonder what I was doing wrong.”

my first published color pictures: Apollo XI launch (1969)

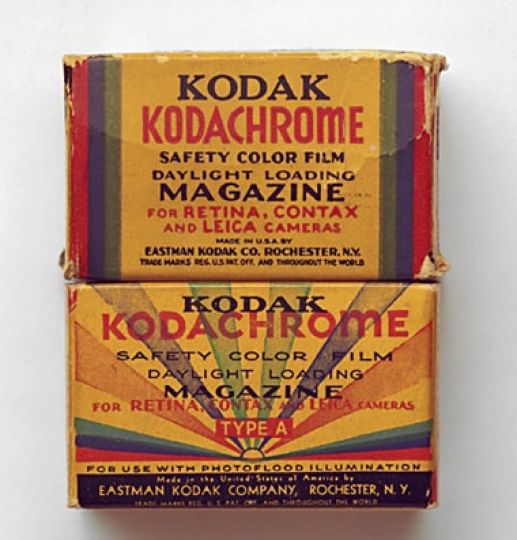

Somewhere in the search to push myself to a higher strata, I thought I would try the film that had a reputation but which almost no one in the “news magazine” business used, because of the time needed to actually handle the processing. Kodachrome, a film which dated to the 1930s was known to have a more demanding technical side (your exposures had to be bang on!) but when you succeeded, the results were light years beyond the Ektachrome type films. There were only a handful of labs in the world which processed the film – requiring a strange and mysterious set up which only Kodak could supply. The names of the lab locations eventually became little code words for Kodachrome shooters. You didn’t need to specify Kodak: just mention Page Mill (Rd – Palo Alto), Lausanne (Switz.), Fairlawn (NJ), and right away you were in that special realm. The world of the Little Yellow Boxes. In each Kodachrome lab, no matter where it was, the pictures were mounted into red cardboard mounts with the word Kodachrome in red on one side, and the date (month, year) on the other. The boxes were identical, be it Sydney, London, or Fairlawn. We could recognize a Kodachrome box a block away.

The most astonishing thing about opening your first box of Kodachromes was discovering that in fact, your lenses really WERE sharp. Somehow the film was just waiting to etch those images in a way no other film could do. It was just a joy (when you didn’t screw up in the field) to open up and scan quickly through a box just back from the lab.

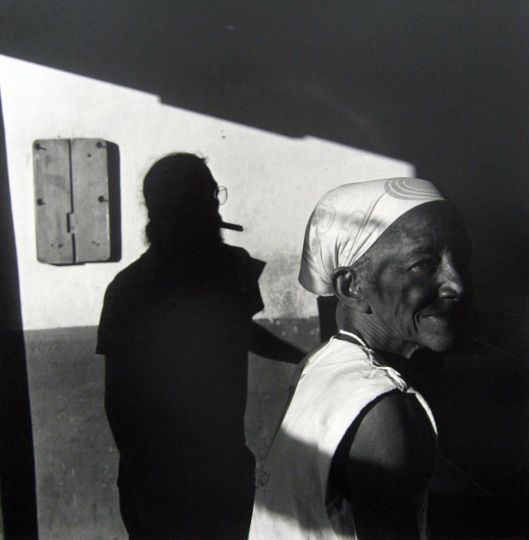

A fallen martyr- the Iran Revolution (1979)

The original film was an ungodly slow ASA 10. In the fifties that was advanced to 25 as the renamed Kodachrome II became a standard for those seeking the sharpest, richest images. In 1974, rumors of a new version surfaced with the introduction of Kodachrome (KR) 64. At last a film fast enough to shoot almost anywhere, and sharp enough to be just about perfect. The first roll which came my way was in early 1974. I was in Paris and had just photographed the campaign of Valery Giscard d’Estaing, the new French President. I had a quick portrait session with him (yes, typical Burnett window light, thank you!) and included in that shot a roll of head shots done on KR64. A week later one of those frames was the cover of TIME magazine.

Boy in Ethiopian refugee camp (1984)

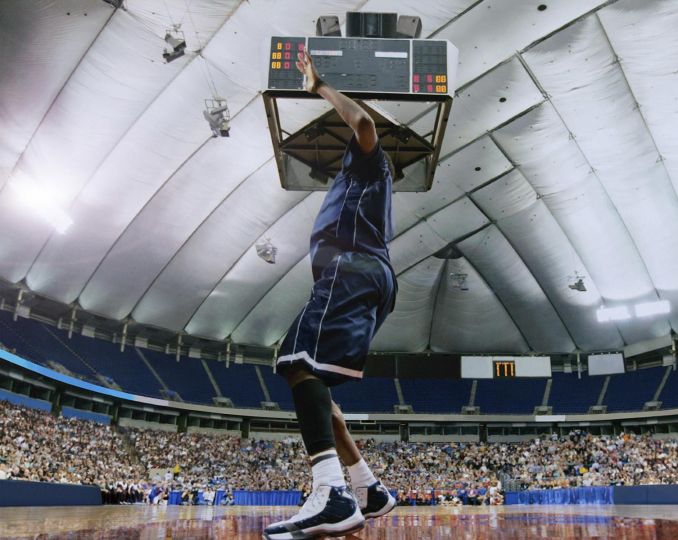

That was about all I needed for convincing. Mindful of the disadvantage that the extra day or two, or sometimes 3 or 4 would cost me in fighting for magazine space, in almost every story I did for the next fifteen years KR would be my film of choice. In the late 80s, Kodachrome 200 was introduced, an amazingly beautiful film that was perfect for sports, and low light level politics. You could shoot that Kodachrome sharpness and tight grain in places were you could barely see WHAT you were photographing. Each was better than the next. It was a gift to those of us who tried to tell the story of the world, and do it with some sense of visual style.

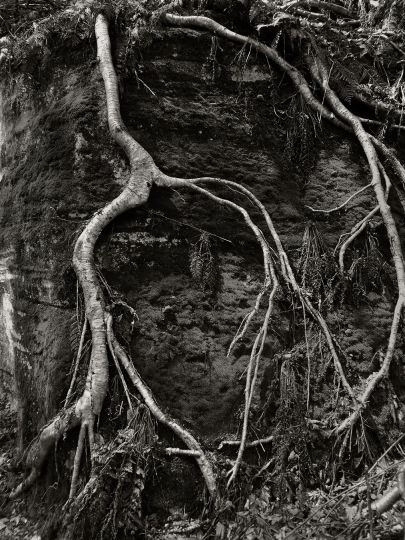

The Outsiders (1982)

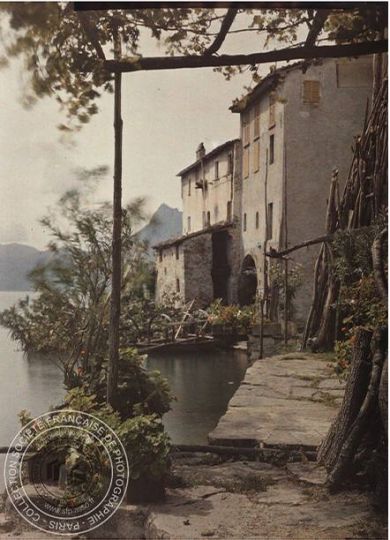

Coming back from a two week trip to Ethiopia and Eritrea in 1977, I stopped on the way back from Khartoum at Geneva, and holed up at a swanky Lausanne lake front hotel while the Kodak lab handled my many dozens of rolls. It took two or three extra days, but when I look at those pictures now, and imagine what they would look like on Ektachrome films, I know I made the right call. More than once my film wouldn’t be in contention on a story, simply because while other photographers pictures (done on Ekta) would be dropped into magazine layouts, my film would still be at Kodak being processed. Then, on Friday at noon, just hours before the deadline to send the pictures to the engravers, one or two of my Kodachromes would wander on to the picture editors desk, like a tardy school boy rushing to beat the bell; the richness and sharpness of the images would cause them to make a last minute swap, and my picture would run in the magazine after all. It was always a crap shoot, and one which I am happy I got to roll snake eyes for.

American troops, Grenada (1983)

As digital began to displace film in the late 1990s (and cameras too: the latest and last generation of film cameras, the Nikon F5, the Canon EOS 1 v, the Leica M7) a system which had finally reached the pinnacle of beauty and quality, and efficiency was sacked almost overnight. Thirty five mm film, which had ruled the roost for forty years, was suddenly treated like an outcast, a victim of convenience, and especially of ‘time.’ Editors know that the news is what JUST happened, not what happened yesterday. Film, for all its charms, just couldn’t compete in the world of the breathless 2 minute news cycle. So as with most things worth preserving, Kodachrome was given the ax, tossed under the bus of progress. (Another metaphor awaits, dear reader!)

Couple with cherry pie – Montana (1982)

Truth be told, the last ten or 15 years were not easy for anyone what actually WANTED to shoot KR. Kodak slowly closed labs around the world, and the mere act of getting your film souped became Herculean. (Actually, Hercules shot tri-x.) So when the marketing people at Kodak (this actually happened ten years ago at a dinner in DC) would say that “there is no demand for the film anymore… no one wants to use it..” I had to remind him that at some point anyone using the film — or any film — actually wants to be able to SEE WHAT THE HELL THEY SHOT! You can’t expect people to wait a week to see their work. The technology existed to create small mini Kodachrome processing machines which could reasonably be installed at any good sized one-hour lab in the country. But for reasons known only to the geniuses at Kodak’s planning department, no serious consideration was ever given to supporting that project. They sure could have sold a lot of film if only we’d been able to see it in a timely manner. Perhaps it’s a parable for what technology is doing to our society.

Balloon race, Paris (1983)

The need to speed up everything, to be sure that there is no hesitation, no gap between something happening, and its being reported. There is something unfortunate that happens when speed and velocity become the key determinants in a society. Much is lost which requires thought and introspection. We simply rush from the last quickly delivered moment to the next, robbing ourselves of the time it takes to reflect, even briefly about where we are going.

Ethiopian mother and child (1984)

At the time,like most KR shooters, I probably didn’t know how lucky I was, but I’m glad I had a chance to live in the last half of the Kodachrome generation. It’s a time that won’t come again. We’re just sayin’….David