by Igor Manko

The aim of the Kharkiv School of Photography: from Soviet censorship to new aesthetics project is to provide an historical awareness of the emergence and the ideological and aesthetic development of the Kharkiv School of Photography from late Soviet (1970’s – mid 1980’s) to post-Soviet (mid 1980’s – 1990’s and 2000’s) periods.

Fine art photography in the city of Kharkiv (Ukraine) since the early 1970′s is a story of how a collaborative effort of eight rebellious artists has, over the years, led to the emergence of an art school with a diverse, but distinctive and recognizable visual language.The means of artistic expression, developed by this group and their followers, are still alive for today’s artistic community both in Kharkiv and in the whole of Ukraine.

The uniqueness of this phenomenon lies in the fact that, unlike other artistic communities of the USSR, the Kharkiv School of Photography was not mirroring Western aesthetic trends. Rather, it developed its own visual language based upon the Soviet realities, and incorporated itself into the evolution of the Soviet avant-garde. Thus, Kharkiv artists pioneered conceptualism in photography, which was unknown in both Ukraine and the USSR at the time.

The Kharkiv School’s achievements, with an exception of two or three individual artists, are not well-known internationally. This project provides a curatorial and critical platform, to educate and engage the audience with the history and achievements of the Kharkiv School of Photography, formed in the city of Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Introduction: On socialist realism

The Kharkiv School of Photography’s aesthetic principles emerged within the nonconformist art movement in the USSR as an attempt to break free from the conventional imagery of Soviet photography dictated by the predominant socialist realism doctrine in art.

Socialist realism, the prescribed aesthetic method of Soviet art, demanded of the artist “the truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development… linked with the task of ideological transformation and education” in an attempt to create “an entirely new type of human being.” Socialist realism was officially introduced in 1934 for the purpose of smothering the freedom of artistic expression and suppressing the 1920′s avant-garde movement in the USSR as part of the Communist party’s broader onslaught on all freedoms and the start of the political repressions of the Soviet people.

Proclaiming socialist realism as the only true method meant that all other forms of art were denounced as decadent and therefore anti-Communist and were severely censored. A dissident Soviet writer Andrei Sinyavsky in his 1959 essay On Socialist Realism mockingly compared it to a teleological system that would not tolerate the heresy of debate or doubt: “If even once you allow an assumption that God had unwittingly sinned with Eve, and, jealous of her and Adam, expelled the unblessed spouses into a forced labor camp on Earth, the entire creation concept will go to the dogs, making it impossible to restore the faith in the same form.”

The practical application of socialist realism resulted in oversimplified and quasi-optimistic depiction and glorification of the Soviet reality, “the ‘boy meets girl meets tractor’ genre” (Sheila Fitzpatrick ‘The Cultural Front: Power and Culture in Revolutionary Russia’, 1992, Cornell University Press, p. 209), in all spheres of artistic endeavor. In photography, socialist realism allowed an artist quite a limited pictorial repertoire. Beautiful Soviet women and handsome Soviet men, engaged in an activity beneficial to the Soviet society (preferably, a factory, a collective farm or a construction site); romantic images of young Soviet people with not more than a hint on eroticism; wise elderly Soviet men with long white beards; happy well-dressed Soviet children on their way to school; landscapes showing the beauty of the Soviet nature – this inventory practically exhausts the list.

Moreover, artistic photography in the USSR was seen as exclusively amateur practice. While artists in other media had their “unions” that allowed them a professional status, art photographers had to be employed elsewhere and engage in art during their leisure time through amateur “photoclubs,” where the above-mentioned “Soviet aesthetics” flourished.

Beginning: The Vremya group (early 1970-s – mid-1980-s)

Anatoly Makiyenko, Oleg Malyovany, Boris Mikhailov, Yevgeni Pavlov, Yuri Rupin, Alexander Sitnichenko, Alexander Suprun, Guennadi Tubalev

In the early 1970’s, the beginning of what later became known as the “period of stagnation” in Soviet Union history, eight photographers in Kharkiv, Ukraine, joined efforts in fighting the Soviet aesthetic canon and formed an independent (read underground) group of art photography. They called themselves the Vremya Group. The name Vremya (“время” means time in Russian) suggested a move away from traditional imagery towards an innovative form of visual expression.

The Vremya Group started its fight for artistic freedom by trying to look behind the ideological façade of socialist realism. They pictured food shortage queues, drunks, and whores. They chronicled the hypocrisy of May Day demonstrations and the pomp of Victory Day parades, devastated streets, crumbling down suburbs, and abandoned countryside. They portrayed ugliness, nudity, and lust.

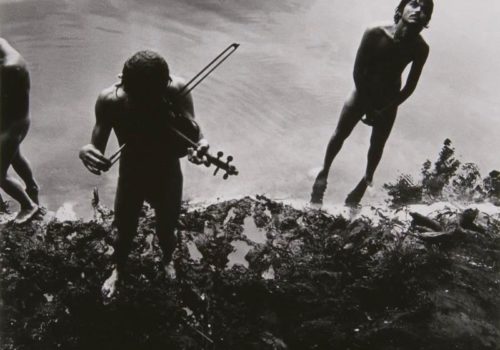

This kind of artistic activity was far from safe in the USSR. Taking photos of a number of objects and in certain places, like plants, train stations, Communist party buildings, or even bazaars, was prohibited. A person with a camera could be taken in for interrogation and accused of spying. Oleg Malevany was tailed by a KGB sleuth when they wanted to know how he managed to get his photos across the border for international exhibitions. Boris Mikhailov was fired from his job when a KGB search found photos of his nude wife in his darkroom. The story goes that expecting pornography charges he went to consult a famous Kharkiv lawyer. The lawyer browsed through the photos and said: “Every intelligent person can see that this is not pornography, but you are not going to be tried by intelligent people.” Alexandr Suprun used a candid camera concealed in a shopping bag and an ingenious device to operate it to get material for his photomontages. But despite their exhibitions being canceled, despite censorship and persecution from all sorts of ideological watchdogs, official art critics of the KGB who would search their darkrooms and apartments, the artists managed to secretly create new art and exhibit it. Their images undermined the Soviet Potemkin villages in art and broke the official taboos. Eugeny Pavlov’s The Violin series showing nude young men in a deserted spot produced the effect of an exploding bomb when it was published in Fotografia magazine in Poland in 1973. Pavlov confessed that after he was subpoenaed by KGB for interrogation he considered burning the Violin negatives.

But the artists were soon to discover that at least one of the socialist realism dogmas – stating the “inextricable connection” between form and content – was, after all, true, and that the conventional old means of art photography expression were not good enough for the sought-for thematic novelty. Unified by the spirit of independence and rebellion, they developed the “knock out theory,” which claimed that shocking the viewer was the only mean to produce an aesthetic impact.

Thus began the search for a new visual language in Kharkiv fine art photography.

The uniqueness of this phenomenon lies in the fact that, unlike other artistic communities of the USSR, the Kharkiv School of Photography was not mirroring Western aesthetic trends. Rather, it developed its own visual language based upon the Soviet reality, and incorporated itself into the evolution of the Soviet avant-guard. John P. Jacobs in “After Raskolnikov: Russian Photography Today”* wrote: “In fact, only in Kharkov, under the guidance of Boris Mikhailov, did photographic conceptualism actually flourish in Russia. Until (…) 1990 (…) photographers throughout the USSR, including Moscow, remained hostile to the link of photography with conceptualism.”

The underground artistic movement of Kharkiv photographers of the 1970′s gave life to a new contemporary aesthetic system in photography which was taken further during the Perestroyka years (1986 – 1991), when ideological barriers were gradually dropped and habitual attempts at censorship lost its dramatic consequences. Later in the 1990′s and 2000′s, the continuity was preserved. Since the mid-1980′s, younger generations of photographers have been joining, adopting and further developing the new aesthetics, thus postulating the emergence of a school of fine art photography with common goals and shared principles.

Continuity: The Gosprom group and others

The Gosprom group: Sergey Bratkov, Igor Manko, Guennadi Maslov, Konstantin Melnik, Misha Pedan, Leonid Pesin, Boris Redko, Vladimir Starko

Non-aligned artists: Andrey Avdeyenko, Igor Chursin, Igor Karpenko, Victor Kochetov, Roman Pyatkovka, Sergey Solonsky

The Kharkiv art scene in the mid-1980’s felt like a bubble ready to blast. With Gorbachev announcing Perestroika, the totalitarian Soviet state grudgingly loosened its ideological grip, but the emerging freedom (and the freedom of artistic expression) were still a moot concept to be defined.

The Gosprom group were producing black and white photographs using closed down aperture when shooting and “point light” when printing images to achieve extra sharpness and depth of field. They were interested in documentary photography and, albeit to different degrees, influenced by their famous predecessors the Vremya group. “Nobody really believed that Perestroika would work out, but we all liked to be allowed to make more noises”, Maslov recalls.

In 1987 the first grand-scale exhibition of Kharkiv photography (both the Vremya group and the younger artists) attracted crowds of spectators lining up to enter. The art community resisted the attempts by the KGB to close down the exhibition that violated a whole bunch of Soviet taboos. A public discussion was initiated, which salvaged the show for 10 days and further aroused the interest of visitors. The exhibition saw an unprecedented attendance of about 2000 visitors daily.

In the 1990s artists of the “second generation” of Kharkiv photographers while working alongside their older colleagues built on the predecessors’ approaches to master their individual artistic styles. It was the time when a number of the most important bodies of work in the history of Kharkiv photography were created.

Continuity: The Shilo group and others

The Shilo Group: Vladyslav Krasnoschok, Sergiy Lebedynsky

Non-aligned artists: Igor Chekachkov, Bella Logacheva, Roman Minin

The 2000’s showed further dissemination of Kharkiv School ideas. In 2010 the Ukrainian Photographic Alternative (UPhA) Association was formed to bring artists from all over Ukraine together in an effort to withstand the onslaught of traditional tastes found in the National Photography Union. Misha Pedan and Roman Pyatkovka, the Kharkiv School ‘second generation’ photographers, are among UPhA’s founders and coordinators. A number of younger emerging artists, both from Kharkiv and other regions of Ukraine, used this aesthetic context as a springboard in their artistic research, continuing the traditions of Kharkiv photography today. Thus, the Shilo group (consisting at different times of four, five, three and two artists) made a number of well-aimed postmodernist comments on fundamental Kharkiv School aesthetic approaches. In their Finished Dissertation, Negatives Preserved, etc., they used characteristic Kharkiv photography techniques like manual coloring, conceptual “bad photography” or collage.

Recently Sergiy Lebedinsky founded The Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography and started forming his collection. Igor Chekachkov and Roman Pyatkovka run a photo academy teaching students in Kharkiv School aesthetic principles.

The platform Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics is a part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute. It is dedicated to the promotion of the Kharkiv School of Photography achievements among the wider international audiences and its introduction to the all-European artistic context.

Igor Manko is a photographer from Kharkiv, Ukraine. He has been a member of the National Union of Fine Art Photographers of Ukraine since 1992. He holds a degree in linguistics and is the director of a language school. He exhibited his photographic works in Kharkiv, Kyiv, Moscow, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, and Denmark.