Archives – October 2012

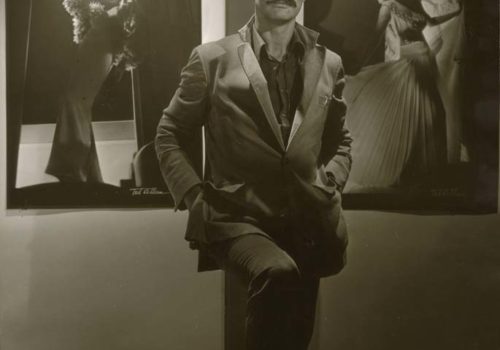

John Kobal, who died twenty-one years ago this month, was a pre-eminent film historian and collector of Hollywood film photography. The author of over thirty books on film and film photography, he was known for his creative and exuberant personality, as well as his voracious knowledge of the minutiae of film and photography lore. He is credited with essentially ‘rediscovering’ many of the great Hollywood Studio photographers – George Hurrell, Laszlo Willinger, Clarence Sinclair Bull, Ted Allan, Ernest Bachrach, Ruth Harriet Louise, ER Richee among others – who were employed by the movie studios to create the glamorous, iconic portraits of the most famous and compelling stars of the day that now epitomise the Golden Age of Hollywood. Kobal’s mission in the 1970’s and 80’s was to reunite these forgotten artists with their original negatives and produce new prints for exhibitions he then mounted worldwide at, amongst others, Victoria & Albert Museum, London; National Portrait Gallery, London; Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC and LA County Museum, Los Angeles. These prints, along with the original vintage prints from the studio days, form the core of the John Kobal Foundation Archive that he donated to the foundation prior to his death in London in October 1991.

‘June Duprez, his princess in ‘The Thief Of Baghdad’, cooked him gourmet meals; Olga Baclanova fed him caviare. Joan Crawford sang to him, Miriam Hopkins recited Byron’s ‘The Prisoner Of Chillon’, Tallulah Bankhead taught him to smoke and Marlene Dietrich let him sleep on a sofa, baskets of flowers at his head, in her hotel suite.’

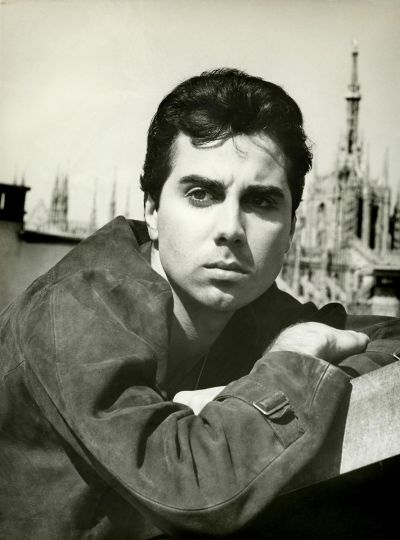

Kobal was born in May 1940 in Linz, Austria, of a Ruthenian father and an Austrian mother, his original name being Ivan Kobaly. He emigrated to Canada with his family when he was ten. From the first he was a passionate filmgoer and one of his earliest memories was sneaking into a Rita Hayworth movie being shown to the American occupation forces in a hall next to his grandmother’s house in Salzburg.

Though he seems to have assimilated very rapidly into the life of Ottawa, probably the dislocation of the move emphasised his tendency to live more intensely in film than in reality. A love affair with the movies had begun when Kobal was a boy in Austria and continued when his family immigrated to Canada. He later wrote that “Hollywood exerted a powerful charm on the imagination of a young man used to living in emotional isolation.” Along with seeing every movie he could, his passion for collecting was ignited and Kobal bought (and saved) fan magazines and started sending away for the 8 X 10 glossies that were distributed by the studios and delivered into the anxious hands of fans worldwide. Popular since the earliest days of motion pictures, these magazines and the flood of images produced by the studios kept favorites in the minds of fans and titillated movie goers, even those living in far away places.

He was an actor at school, most noted according to his own version for picturesque disasters which surrounded his every appearance. Undeterred, at the age of 18 he headed off to New York with the intention of going on stage professionally. Shortly afterwards he arrived in England, which was to remain his home for the rest of his life. He spent the next four years touring the English provinces in various plays spending his spare time scouring antique markets and second hand bookshops for items of film memorabilia and film stills. He always carried the picture collection with him, always augmenting it when he got the chance. In 1964 he went to New York where he freelanced for BBC Radio’s ‘Movie Go Round’ programme and later became their US film correspondent. The American Film industry was in a period of major transition and the Hollywood Studios were closing down their offices and discarding old publicity materials – posters, photos etc. – that few regarded as of any value at that time.The studio system was long dead and television had effectively drawn audiences away from movie theaters. The nostalgia craze of the baby boomers was still a decade off. During the 1960s five of Hollywood’s eight major studios — MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, Universal and United Artists — were sold off to conglomerates, the men in suits having little interest in the history of the businesses they were acquiring. A collective insanity swept through Los Angeles during this period of consolidation and many studios shed treasure troves of publicity and promotional material created to support the films that entertained audiences since the 1920s.

Kobal collected any images he could find but what had the most resonance for Kobal, however, were original portraits, the 11 X 14 inch silver prints that froze in time for him a moment in American cultural life when glamour dominated the movies. They were a tangible connection to the past and he gobbled up them up wherever he could find them. When Kobal first started seriously examining and acquiring Hollywood portraits and stills, this material was considered nothing more than insignificant Hollywood ephemera. Only a few film enthusiasts, including Kobal, scrambled and competed to acquire original studio photographs. Kobal did, however, collect better than the others, and in the end used his extraordinary collection in the service of restoring the reputations of the photographers who had helped create the stars in the first place.

“For me,” wrote Kobal, “the ‘movie star’ was always the most remarkable thing about the movies.” And by movie star, Kobal meant the great faces that graced cinema from its beginnings, through film noir and into the 1950s. Like all fans, Kobal loved the movies, but in the period before video and DVD there were few opportunities to see old films. He shared with fans from the decades before he was born an insatiable desire to learn as much as he could about his favorites and consumed every tidbit offered in fan magazines and any other promotional material he could find. When Kobal moved to New York in 1964, and later Los Angeles, he was overwhelmed by the fact that television showed movies throughout the day and night, albeit often butchered to slip a two hour movie in a ninety minute slot including commercials. Here Kobal was introduced to more of the great faces of the past, many long dead, retired or now decades past their prime. Meeting the stars whose faces flickered on late night television became his holy grail.

‘It was Tallulah Bankhead who unlocked Hollywood for me. One night she called George Cukor and said ‘Dahling George…’ and after they gossiped forever, she remembered why she had called him in the first place and said, ‘I have this diviihhhne young man here, and he’s going to Hollywood and he doesn’t know anyone and you know everyone; and he’s really a most serious young man.’ She looked at me to make sure, and then mortified me by telling Cukor that I was broke ‘but presentable, dahling. And he knows everything about everybody’s movies’

Once the doors of Hollywood were open to Kobal, obsessive accumulation became the hallmark of his acquisition of star portraits. He acquired single prints, small collections and when the opportunity arose a star’s or photographer’s archives. All Hollywood photography fell under the domain of the studio’s publicity departments and every photograph taken served, in one way or another, the promotion of a film or star and, by association, the studio’s brand. As Gloria Swanson told Kobal in 1964, “Audiences make stars, either they like you or they don’t.” These images were after all an important currency of Hollywood. The careers of legendary figures such as Crawford, Gable and Cooper, Kobal suggested “were made possible through photography and would probably not have existed without“… Long before the paparazzi snaps, which replaced the portrait in the 1960s as the fan’s favorite vehicle of connection to stars, studio-controlled publicity photos chronicled the lives of stars on screen and off. Although these might seem artificial in contrast to the lively intrusion of the rapid fire triggers of today’s digital cameras, they recorded an era when fans looked up to the stars as templates of manners and fashion.

Studio portraits taken at MGM and Paramount were available in the greatest numbers as Hollywood’s top two studios competed with one another for stars and publicity. Kobal may not have consciously selected MGM as his area of greatest interest, but the combination of availability of images and the coincidence of his relationships with George Hurrell and especially Clarence Sinclair Bull gave him an unprecedented access to MGM material. This resulted in Kobal acquiring a practically encyclopedic collection of portraits of MGM stars and featured players. There might also have been something different about MGM photographs, as longtime studio photographer Bud Graybill suggests, “One thing about MGM, though, was that the idea behind the stars was to make them more glamorous, more remote, not so accessible.”

As Kobal met one great lady after the next from Hollywood’s glory days and assiduously collected the portraits that helped each become a star, he started to understand the complexity of not only creating, but sustaining, glamour. In a typical Kobal turn of phrase he noted, “Glamour had been sparks thrown off by the giants in their play, and it was those electrical flashes that made them fascinating.” Discussing portraiture with Kobal, one of those giants, Loretta Young, recounted, “We all thought we were gorgeous because by the time they finished with us we were gorgeous.” Young was, perhaps, being unnecessarily modest, but it is true that even the most beautiful actress received from the hands of her photographer an extra polish and shimmer. “The individuals who were the source of the sparks” according to Kobal, “could never be manufactured, but they had been harnessed to burn as a flame which was controlled by the studio.” This did not occur accidentally or haphazardly. “What happened in the galleries” wrote Kobal, “was an extraordinary thing, something that was beyond the ken of the studios and owed nothing to contracts, scripts or the publicity department.” Performers worked as hard, or as Kobal saw it, perhaps even harder, in the portrait studio than on the set. “To achieve the effects of the great portraits, it was necessary for the sitters to reach a state of trust with the photographer so total that they would unconsciously reveal the very hunger that had driven them to the place where they now found themselves.”

“I photographed better than I looked,” Crawford told Kobal, “so it was easy for me…I let myself go before the camera. I mean, you can’t photograph a dead cat. You have to offer something.” Greta Garbo, whose languid style belies words like “hunger” and “driven”, was, nevertheless, as great a portrait subject as she was a film actress. Kobal would have us understand that whatever it was that made Garbo Hollywood’s greatest film star was also working at full throttle in the portrait studio. Katharine Hepburn put it succinctly, “If you are in the business of being photographed, you must like to have your picture taken, otherwise you shouldn’t be doing it. It’s part of your job.”

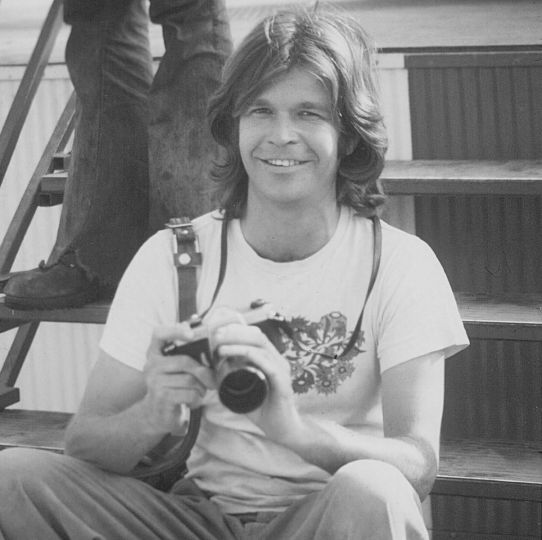

Like so many stories about John Kobal, the one about his notable role as a connoisseur, collector and chronicler of Hollywood photography begins with a movie star. Working as a journalist in 1969, Kobal visited the set of Myra Breckenridge to interview screen legend Mae West. His reporter’s credentials granted him access to the set and while awaiting summons from Miss West, Kobal had the opportunity to meet members of the film’s crew. Making small talk with an on-set photographer, he learned the man’s name was George Hurrell. This surprised Kobal, for he recognized the name from the credit marks embossed or stamped on many of the Hollywood photographs he had collected since childhood. But those photographs were from the 1920s and 1930s, and were images of the greatest of Hollywood’s stars, Davis, Garbo, Gable, Harlow. Could it be the same man almost four decades later, still practicing his craft on a movie set?

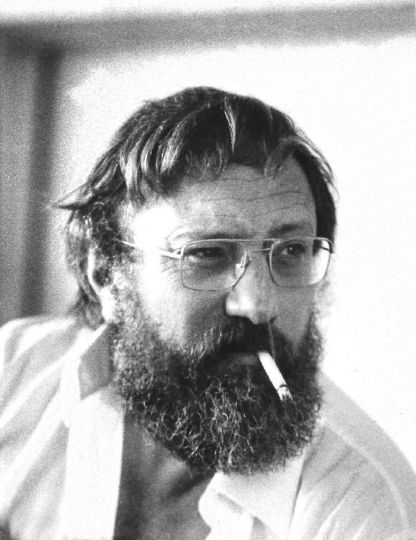

Following this auspicious meeting, Kobal and Hurrell forged a friendship, which allowed the young man to learn from a firsthand source precisely how Hollywood’s glamour was constructed. Although movie stars were catnip to Kobal, after meeting Hurrell he became almost as voracious in locating and interviewing Hollywood photographers. By the 1970s a majority of the photographers who had worked in the twenties and thirties, like their subjects, were retired and a few had died. What made Kobal’s task even more complicated was the issue of photographer’s credit that surrounded studio photography.

While many portraits were embossed or stamped with the photographer’s name, scene-stills were almost never credited. Slowly, and later frantically, Kobal set about attempting to discover just who had taken what picture. Kobal did not meet everyone who shot portraits and stills in Hollywood but he was the first who tried to make sense of their important contribution to movie-land history. In his quest to discover the whereabouts of the surviving stillsmen Kobal came to know, along with Hurrell, Laszlo Willinger, Robert Coburn, William Walling, Ted Allan, John Engstead and Clarence Sinclair Bull.

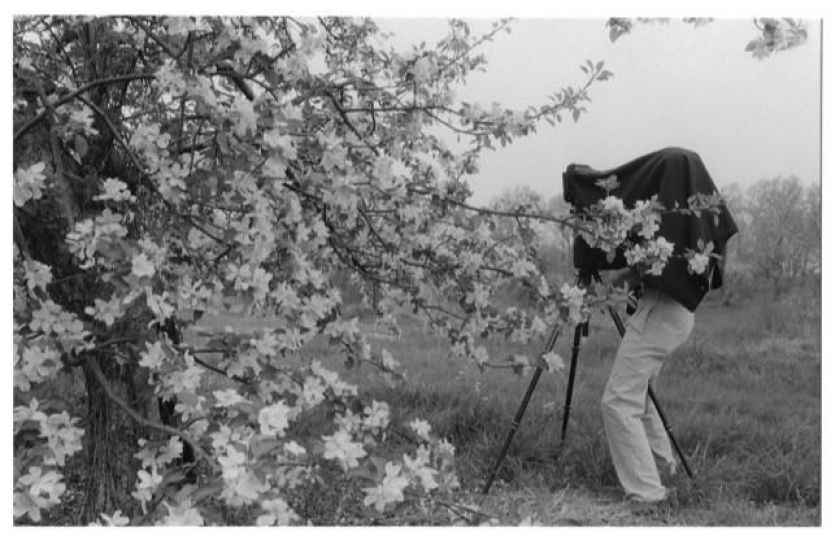

Each would share his memories and print from his negatives. In return Kobal started what became his most important work — publishing the anthologies of the photographers’ work that resuscitated forgotten careers. Work that is perhaps the most perfect record available of the history of Hollywood’s first fifty years. Kobal recognized the important role studio photographers had in developing the images of the stars and chronicled this previously ignored aspect of film history in a succession of books beginning with Hollywood Glamour Portraits: 145 Photos of Stars 1926-1949 published in 1976. His most important work, The Art of the Great Hollywood Portrait Photographers (1980), was the first serious systematic study of the genre and had the added bonus of being both magnificently illustrated and sumptuously produced. In that book he charted the terrain of Hollywood glamour and provided glimpses of the (mostly) ladies who sat before the cameras and the workings of the (mostly) men who created the illusions. In total Kobal authored, co-authored or edited thirty-three books, many illustrated from his own holdings.

Kobal was the first to organize museum shows devoted to Hollywood portraiture. His inaugural effort was at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1974, a show he described as “the first exhibition of the Hollywood group.” This was followed by shows he mounted at The Museum of Modern Art (New York), as well as the National Portrait Galleries in Washington and London. The first museum exhibition devoted to the career of one Hollywood photographer was The Man Who Shot Garbo, a monographic exhibition on Clarence Sinclair Bull that opened at the National Portrait Gallery (London) in 1989. It is apt that Bull’s career should be the first thus to be explored because no photographer shot as many famous Hollywood faces. Katharine Hepburn wrote the foreword to the accompanying eponymously titled book, The Man Who Shot Garbo. She called Bull, “one of the greats” and ended her comments with: “Clarence Bull! And the National Portrait Gallery! WOW!”

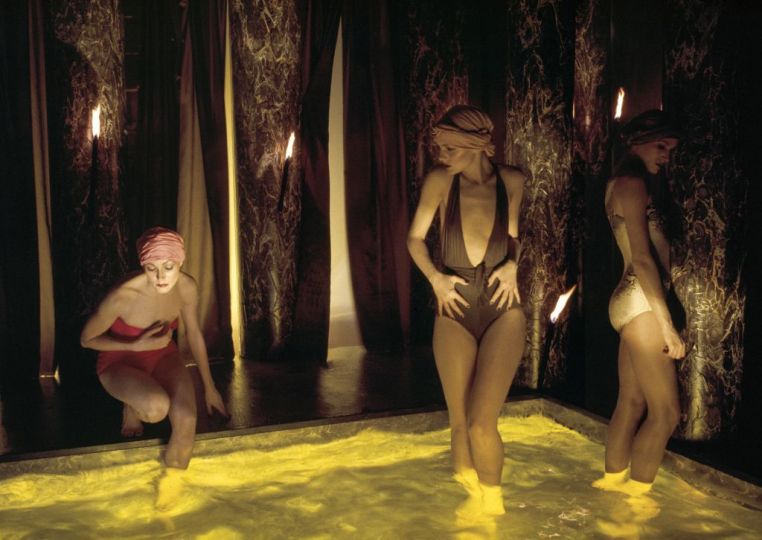

Bull’s tenure at MGM, 1924-1961, matched the period now defined by the old chestnut, Hollywood’s Golden Age. There is no question that it was the golden age of Hollywood portraiture. The year Bull retired, 1961, a new sort of photography was beginning to creep into the mainstream of studio film promotion and the Hollywood press. The candid would soon replace the portrait as the type of image fans most wanted to see. Magazines started publishing snaps of Elizabeth Taylor between planes and yachts, and Greta Garbo as seen beneath a floppy hat through a telephoto lens. Is it a coincidence that Bull left MGM the year Fellini’s La Dolce Vita introduced to the world the character Paparazzo, and the paparazzi were born?

Kobal recognized this shift in attitude toward Hollywood photography and largely limited his collecting to work created before 1960. He identified the years 1925-1940 as the scope of his book The Art of the Great Hollywood Photographers and argued that it is from those years that the greatest innovations took place. “After 1939,” wrote Kobal “…[the] effects of fine photography still lingered on, even as film got faster, lenses sharper, cameras more manageable, and negatives smaller, but by the beginning of the 1940s, much of the great work was over.” In earlier books Kobal had chronicled Hollywood photography from the 1940s and 1950s, including the pioneering use of color, but after that decade he was largely silent. The paparazzi held no allure in the Hollywood fantasy so perfectly described by Kobal. His ebullient personality – almost everyone liked him – allowed Kobal to become the impresario of the history of Hollywood photography.

‘To me John was the Claude Levi-Strauss of glamour. He meticulously collected its thousand-and-one stories and images, and laboriously erected out of them cathedrals full of light and life and wisdom and humanity.‘ (Donald Lyons, Film Comment) ’

Film is the only thing of any creative worth that this century has produced. If not, it is still providing the most fun’ (John Kobal)

The above biography of John Kobal was extracted mainly from the foreword to Glamour of the Gods :photographs from the John Kobal Foundation (Steidl , 2008) by Robert Dance © Robert Dance and used here with his permission.