“So what’s it like to work with a legend like him?” is the first question people ask me when I say I work with John G. Morris.

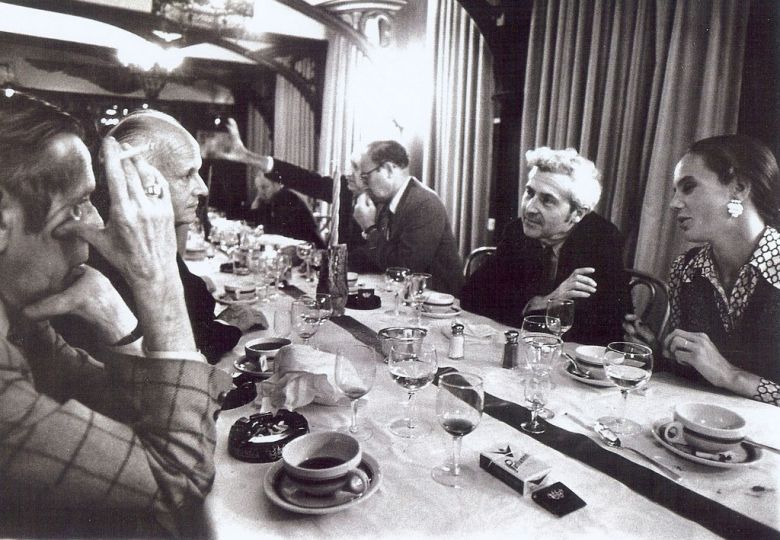

I was introduced to John when he was 93, and soon discovered the world of a man that was disciplined in his every day routine – from reading The New York Times in the morning to having a glass of red wine with dinner (sometimes two), very serious about valuing other people’s time and answering his correspondence as soon as possible, with a lot of affection for his wide circle of friends all over the world. One day, when he signed another one of his newsletters that he had composed and thought about for many days, with “Love, John” he glanced over to me asking, “Anne, do you think I am sending too much love?”

John opened my heart to the world, its people, its challenges, its beauty. He opened and sharpened my eyes and mind for the micro and macrocosms of photography. With every single image that would come across, be it in a newspaper on the internet or walking through Paris, he would explain with his never ending patience a situation in the world, the quality of a photograph or tell one of his anecdotes.

The moment I really understood the soul of a picture editor, was when I showed John Google Image Search for the first time. He typed “Robert Capa”. All the images popped up. John was shocked. Full of outrage he exclaimed, “Who is the editor of all this?”

Observing and listening to John, I was most surprised by how “simple” good photography actually is. He was inspired by many of the great photographers he worked with, but Henri Cartier-Bresson, who was an important friend and influence for him, summarizes best his way of judging photography when he says “you have to put on the same line of sight the head, the heart and the eyes.” So a good photograph becomes almost common sense. This very strong and healthy common sense is the most dominant trait of character when I think about John.

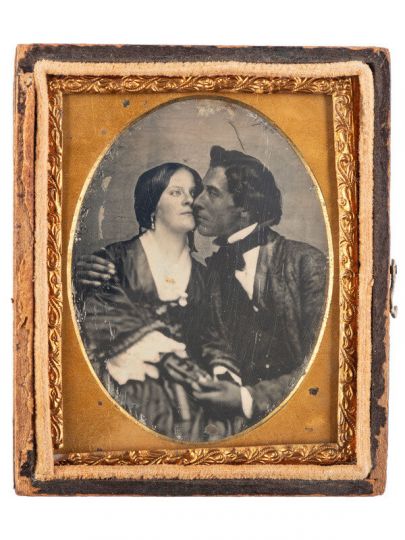

Working with John and discovering his archives, all the precious photographs and documents, each telling a story, an eye blink in a very long life, but yet so important to understand the whole picture of a man who changed the way we see the world through images, my amazement kept being lit like a flame with every new piece of paper, new letter, new photograph that I discovered. John had kept quasi everything. The photograph of how he had climbed on his Chicago childhood backyard tree playing the weather reporter, the Christmas card of John G. Winant, a former governor of New Hampshire that young John had met on the passenger liner on his way back to America from his first trip to England in 1935, Marlene Dietrich’s handwritten note that she handed him after a cocktail at the Ritz Bar in Paris in 1944, the last picture of him and his first wife Dele in Rome taken by David “Chim” Seymour in 1956. The New York Times staff fun collages, his sketch of a “Unicef World Birthright Passport” to ensure each child is properly welcome into the family of man knowing its rights, the photographs of his peace marches, Nick Ut’s signed postcard of his “Napalm girl” photograph that John published on the front page of The New York Times in 1972, which is a daily reminder for him to keep working for peace.

Our collaboration on the “My Century” book and collecting the many memories and stories of his life was the ultimate experience of a great mind at work. Sometimes so enthusiastic and quick in his thought stream that it was hard to follow up. Dear John, here’s to you. Happy 100th Birthday!

Anne Spiller

New York, December 7, 2016

Anne Spiller is the Principal Collaborator and Main Editorial Contributor of the “My Century – John G. Morris” Project and has worked with the legendary Photo Editor since 2010, including judging the annual DAYS Japan International Photojournalism Award for 6 consecutive years.

To find out more and support the MY CENTURY book project visit www.mycenturyjgm.net .