It was at the Tate Modern that Jiawen Hu stumbled upon a photograph by Luo Bonian, a Chinese photographer little known to the general public. She noticed that the work came from the Three Shadows Photography Art Center, an art institution founded in Beijing in 2007.

At the time, Jiawen was finishing her studies. She decided to apply to the center and was hired shortly after. Now the deputy director of the institution, she curated the exhibition “Glinting Light: An Exploration of Luo Bonian’s Photography”—the first-ever exhibition in China dedicated to Luo Bonian’s work. This project is deeply significant not only for Jiawen but also for Chinese culture and history.

Luo Bonian’s work offers a rich testimony to the society, art, and culture of the Republic of China. As Stéphanie H. Tung, a specialist in Chinese photography, noted: “An archive of this scale—nearly 300 vintage silver gelatin prints and an even greater number of negatives from the era—created by an individual photographer in early 20th-century China is extremely rare. Most photographic materials were considered bourgeois and either destroyed or hidden after the Cultural Revolution of 1949.” Thanks to the efforts of Luo’s great-grandson, Jin Youming—a banker and amateur photographer—the archives were rediscovered and shared, finally recognizing Luo Bonian’s pioneering role.

The exhibition, held on the first floor of the Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Xiamen, highlights the milestones of Luo’s career from 1930 to 1940. It explores his favored themes: landscapes, collages, and still lifes. At first glance, these subjects might appear mundane, but they connect Luo to Chinese pictorial traditions and Western modernist avant-garde movements—references that became entirely taboo during the Cultural Revolution. The display also includes personal albums, magazines, vintage prints, and the sleeves Luo used to store his negatives, offering an intimate glimpse into his process.

Born in 1911 into a family of local officials in Hangzhou, Luo started as an accountant at the Commercial Bank of China, a booming sector at the time. That same year, he discovered photography, a costly hobby popular among educated and affluent middle classes.

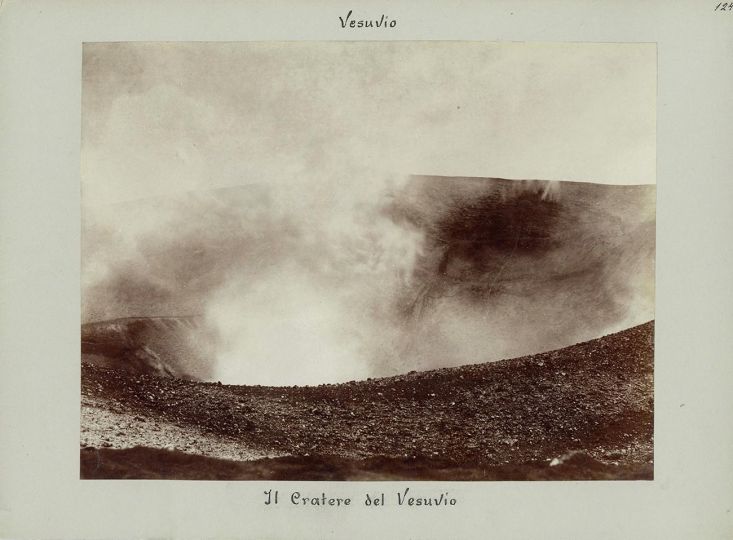

Luo’s work assignments took him to cities like Beijing, Chongqing, Hangzhou, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, as he transferred between branches of the Bank of China. The cosmopolitan atmospheres of Shanghai and Hong Kong gave him access to international publications like Das Deutsche Lichtbild and Pictorial Photographers of America, which profoundly influenced his style, imbuing it with a unique and avant-garde aesthetic for the era.

In his free time, Luo immersed himself in photography, quickly joining networks of amateur photographers. His work appeared in magazines such as Fei Ying, Chinese Photography Magazine, and Kodak Magazine. In 1937, Luo held his most significant exhibition, Friendship, in Shanghai. The exhibition’s calligraphic inscription was done by the renowned writer Yu Dafu, reflecting Luo’s connections with literary, artistic, and political figures of Republican China.

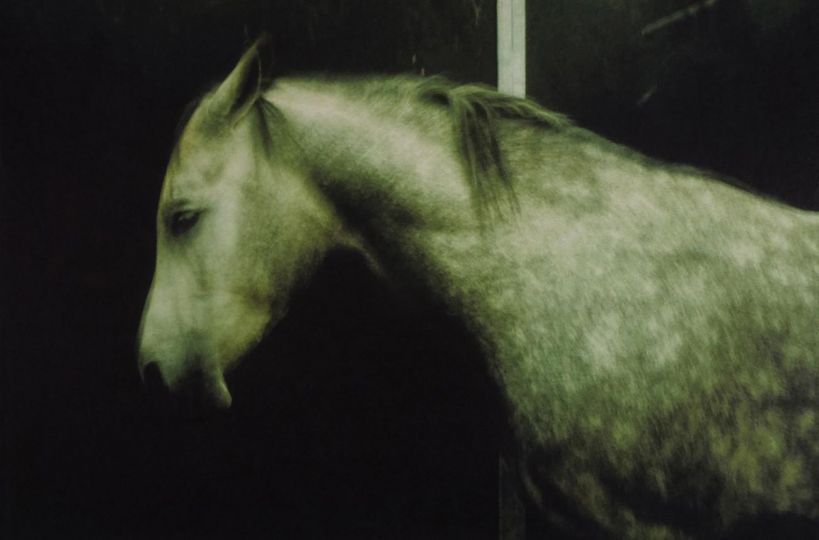

Above all, Luo loved to experiment. His abstract compositions and still lifes reflect a fascination with form, shadow, and light. His collages reconfigure everyday elements like plant veins, bricks, and iron grids—details meticulously selected from daily life. The exhibition explains:

“His technique was ingenious, akin to using a kaleidoscope. Luo would print four photos on each side of a single negative, extract key focal points, and crop them into eight equilateral triangles. These triangles, cleverly paired and symmetrically aligned, created scenes that were both strange and harmonious. His still lifes echo the explorations of light and shadow by German photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch of the New Objectivity movement, opening a new visual domain in contemporary art.”

Despite the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Luo continued photographing, focusing on still lifes and experimental indoor works. Notable examples include a halved cabbage and a statue of an embracing couple atop a sideboard. However, after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Luo stopped photographing due to a lack of resources and political changes. He returned to Hangzhou, away from the public eye and largely shielded from the violence and political purges of the Cultural Revolution. Remarkably, he managed to protect his prints and negatives by hiding them in boxes and albums.

This remarkable exhibition traces the journey of an individual whose talent, perseverance, and dedication convey a message of hope and creative renewal to all who view his work.

Jimei x Arles International Photo Festival 2024

Jimei Art Centre

Bullding 12, XInglinwan Business Contro, Jimoi District, Xiamen

www.rencontres-arles.com/fr/jimei-x-arles-2024international-photo-festival

Three Shadows Photography Art Centre

3F, Bullding 2, Xinglinwan Business

Contro, Jimei District, Xiamen

www.threeshadows.cn/cn