Jean Marquis had chosen the theater, the limelight, the free life of a performer, and the vertigo of words. In the games of love and chance, he threw his lot with Susie Fischer: a whirlwind romance. Aged twenty-three, in 1949, the young man had left the commune of Armentière, Lille, and the world of Pavillon Bleu on the banks of the Deûle, and headed for Paris. He continued to work in theater as a stage assistant. There followed his marriage with Susie, Robert Capa’s cousin, and his introduction to the legendary reporter, the heart and soul of Magnum photos agency founded and run by young photographers. Susie was part of the group and focused on marketing the images. Jean took some photos of stage sets and was in charge of stage lighting, but there is a big step to devoting himself to photography full time… But the idea is there. Capa, always ready with recommendations and proofs of friendship, got Marquis hired as an assistant to Pierre Gassmann, a former photographer working as a printer for his friends. The developing trays of his Pictorial Service held some of the best of contemporary photography. Jean Marquis crossed over from word to image: a revelation!

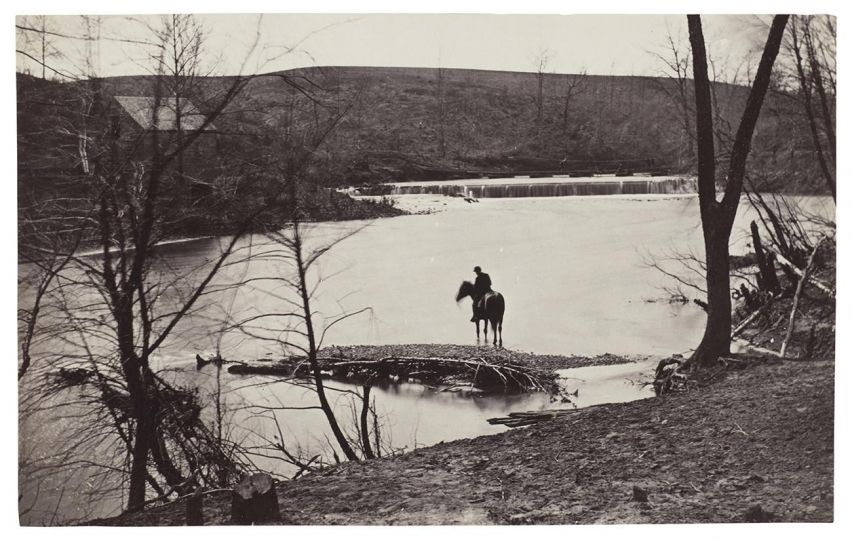

In the spring of 1953, his contract with Gassmann had expired: it was time to plunge into deep waters. His first photo stories: the Foire du Trône, a Sidney Bechet concert, an SNCF train strike… In order to join Magnum, he needed a more in depth story. He returned to the banks of the Deûle, to his native north country. He was flooded by images of the past: the family business liquidated in 1936; the takeover of the Pavillon Bleu, a riverside inn where his radical-socialist father exhorted bargemen amid canals, slag heaps, factories, and mining communities that lived the harsh and solidary life of workers, so close and so distant in their silent dignity.

In the fall, Jean Marquis was fully engaged with this corner of France, the country just barely emerging from the war. He was always hard at work, his sleeves rolled up. This was his first big assignment. The main lines of his work and the vocabulary of his style began to crystalize: his sensibility to the most trivial situations, to ordinary people, and unimportant sites; his spot-on framing, his sense of composition and balanced contrasts; his mastery of light, shadows, and darker blacks.

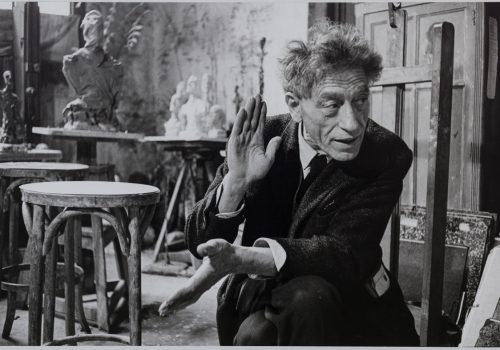

Magnum was a whole new way of life. With Ernst Haas, Inge Morath, Kryn Taconis, and Marc Riboud, Jean Marquis joined a very exclusive club of photographic masters. The camera brought its own gratifications and kept him as spellbound as theater had. Marquis honed his skills, and sized up his abilities and the territories open to professional growth, against the clash of different sensibilities, varied aspirations to excellence, and struggles for influence among the most brilliant artists. Capa would dispatch him to film sets; he also traveled across Hungary, the home of the Fischer brothers; and took full advantage of the opportunities offered.

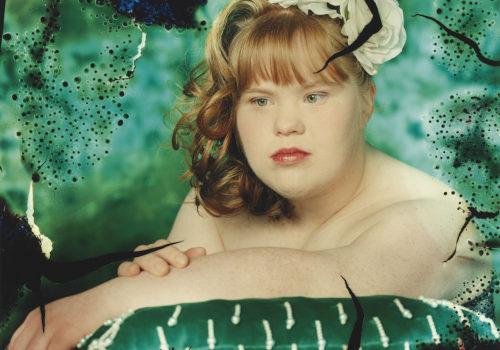

Capa’s accidental death in 1954 altered the power balance within the agency. Susie severed her ties with Magnum. Jean Marquis followed suit three years later. While he was giving up an exceptional community, his connections with the domestic and international press remained intact. The New York Times Magazine, Time-Life, L’Express, Science et vie … continued to supply fresh opportunities. Susie took a post at the Parisian office of Time-Life. An independent photographer and master of his own production process, Marquis was nevertheless subject to the demands of the editors. Fashion, celebrity portraits, film sets, the modernizing infrastructure, national and international news stories piled up in his archives. Edward Steichen, the director of MoMA’s Department of Photography, selected the photograph Rue du Petit Musc for the exhibition The Family of Men. A few notable news stories gained Marquis a leading audience. Commenting on his reportage on the working-class environment with the journalist Béatrix Beck, “Caïn qu’as tu fait de ton frère?” [Cain, what have you done to your brother?”] (L’Express, December 14–16, 1955), Albert Camus wrote: “I defy anyone to read these pages without shame and without protest.” Reporting on assignment and reporting out of conviction, in line with the social aspirations of downtrodden men and women.

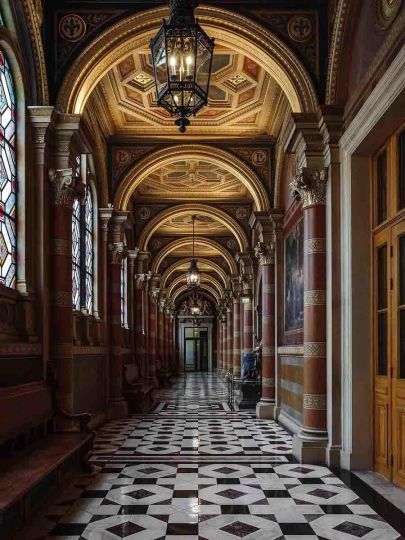

In 1963, the publisher Robert Laffont, building on the success of Léon Zitrone’s book La vie d’un cheval de courses, illustrated by Marquis, invited him to collaborate on Louis Aragon’s book, Il ne m’est Paris que d’Elsa. The poet expressed some reluctance: “I don’t want anyone adding potted flowers to the foot of my poems.” There followed encounters, walks, and monologs: Aragon crisscrossing the Paris “of fake windmills pretending to spin in Montmartre,” exploring the recesses of memory, from the Hôtel Istria to the Rue de Varenne. Marquis engaged with the text, capturing in his images the rustling presence of Elsa: in between words and shadows, and lights. “Day breaks by the Fontaine des Innocents.” Not a single potted flower. The photographs are like signs of farewell suspended between departures and returns, like arms wide opened between the two banks of the Seine, and like time winding around the bridges.

Marquis’s gaze is still distant, imbued with empathy, trained on the dying world of rural France and lost amid the Corrèze countryside. Accompanied by the journalist Lucien Espinasse, Marquis visited the region on multiple occasions between 1965 an 1967. He was keen to bear witness to the living conditions, to the disappearing skills and crafts of a countryside subsisting in age-long harmony. He knew how to frame the splendor of the landscapes shaped by prolonged human labor. Far from being anecdotal, the photographs uphold unadorned humanism. Michel Tournier analyzed its sources in his TV program, La Chambre Noire, on July 3, 1967.

Now over ninety, Jean Marquis works on his archives, annotates his images, and accept to be interviewed. He emanates self assurance for a job well done, questioning the verdicts of History. Susie is still there, sparkling and full of life, the temple-keeper. His work, intertwined with the upheavals of the Trente Glorieuses (i.e. 1945–75), speaks of conflicts, struggles, and grief that marked the era in which abundance, luxury, and opulence were only one side of the story.

Françoise Denoyelle

Françoise Denoyelle is a historian of photography, professor at the École Nationale Supérieure Louis-Lumière, and associate professor at Université de Paris I–Panthéon-Sorbonne. She lives and works in Paris. A version of this article appeared in issue 50 of the journal Faites entrer l’infini in December 2010.