A selective choice of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s snapshots are shown in Antwerp at the galerie Fifty one in partnership with the Lartigue Donation. As the bookeeper of his own journey, Lartigue appears as a solid and talented imagekeeper of the time passing by as well as a sure and precise witness of the evolution of photography.

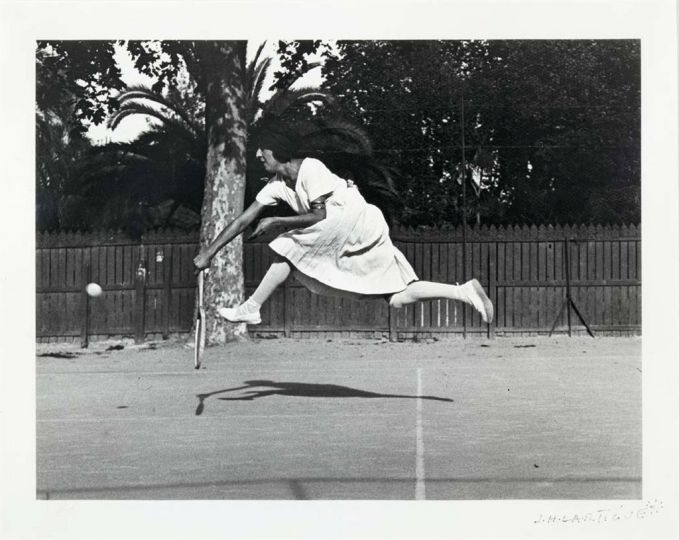

The images of Lartigue seems to be part of our family album, the family of the twentieth century. There are planes without engines, automobiles without airbags, beautiful women and rich people who have fun, whatever the crazy and violent world around. Many iconic images are shown in the gallery, like the one of his cousin Bichonnade, an unmeant image of a free bird flying across a marble staircase, lightened by her smile, the speed, her white»colar»dress and fancy laced leather shoes. There is also this incredible image of the Grand Prix in Dieppe where the newly built strenght of the engine seems to distort the image itself by the power of its speed. Many strong and appealing images makes us remember the path we have achieved in a few decades as well as the talent of a kid who knew, all his life, how to save a moment with a shot of a second.

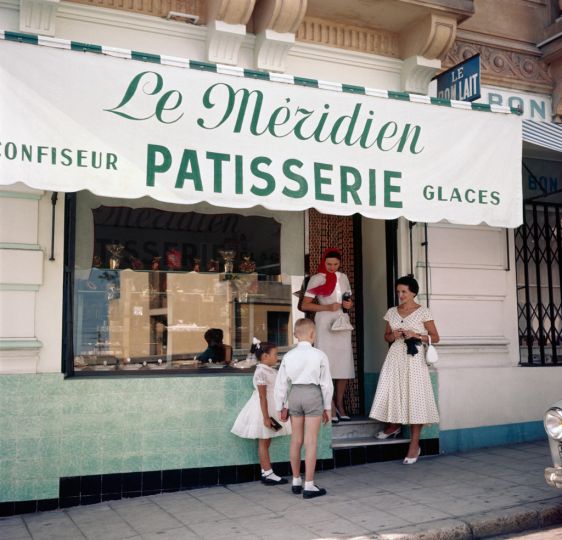

Lartigue liked to catch on film these “instants of life” the same way he was playing as a child, recording a scene in his memory by capturing the frame, the light and the color with a blink of his eyes. To catch the time, to catch and store the time, that was his “thing”. The first feeling you get when entering the cosy and neat Fifty One gallery is a glimpse of smoked desire. Sixteen «cigarettes» women welcomes you. With their tight frames, blurred backgrounds and strong contrasts, these photographs set the tone for the entire exhibition. What attracts the eye is Lartigue’s lifelong passion for women. It is easy to imagine the “emotion” of the young Lartigue when he was taking pictures of the fully dressed «cocottes» in the fancy alleys of the Bois de Boulogne but, closer to our «beauty» canon, are his adult pictures which take us into his private and now public intimacy.

Lartigue’s pictures were not meant to be seen, by anyone but him. All his life, he took pictures, day after day, and glued them in albums, with hand notes of the weather… At the end of his life, he gave everything, pictures, albums, negatives to the French State in order that his compulsive talented work not be lost after his death…. This could be a strange behaviour for a living photographer but Lartigue didn’t earned his life as a photographer like Capa for example but as a painter. He was discovered as a major photographer quite late during a trip in America. It is only after an exhibition of his work in 1963 at the Moma and an «un»fortunate portfolio in Life magazine in the same issue that showed the images of the assassination of Kennedy that his private albums became part of the history of this newly born art called photography. He was 69.

For the record, Lartigue honored his first professional assignment as a photographer in New York, in Central Park, for Harper’s Bazaar. He was 72.

Photography for Lartigue was never a question of art but, since the age of 8, it was an irrepressible need to capture time, not the time of history but, with as much talent as conscient selfishness, the time of his life, and his life only.

The Wars, the turmoil of the twentieth century, the world’s changing around were not Lartigue’s thing. Like a character of Mime Marceau, Lartigue endeavored neither to see nor to photograph evil. But what could have been a banal cluster of memories,in an assortment of lightweight images, has become a full-fledged body of work allowing both historians and art lovers to enjoy and learn from its pages. As much as Lartigue was self-concerned, he was, in photography, filled with this strange thing, this ability called talent, to convey an emotion we can feel throughout the years,

The selection of vintage and collector’s prints, Roger Szmulewicz. made with the Donation Lartigue adds some unexpected images to the well known icons, like this portrait of Bibi (his first wife) and Yvonne Printemps, sitting together in a large leather chair in the living room of Sacha Guitry, the famous writer and stage and film director. For once, Lartigue framed the shot from a distance in order to draw the two women, the two famous women, like an element of the decor among frames, carpets and lights. Exactly as if they were on a theater stage and the main subject was…the stage itself.

The gallery presents also a surprising portrait of Solange David (1929), with closed eyes and mouth heart peinted that could easily been seen as a surrealist Man Ray icon asleep in the arms of Dali. We also discover this amazing Palm tree backlit taken in Menton in 1978 which recalls both the engravings and the stylized movie sets in black and gray of the thirties.

In 1983, a BBC journalist asked Lartigue how he took his pictures. “Do you take a picture with your eyes ? With your mind ?” Quickly, Lartigue, understood the «intellectual» touch of the question and answered simply :»no, not al all, I use my guts and my heart». That is may be why, even if Lartigue dedicated all his living time to be the historian of his own life, his photographs accompagny us long after we’ve left the gallery.

Matthieu Wolmark

Jacques-Henri Lartigue – Instants de Vie

From September 7th to December 2nd, 2012

Fifty One Fine Art Photography

Zirkstraat 20

2000 Antwerp-Belgium

T: +32(0)3 289 84 58

F: +32(0)3 289 84 59

E: [email protected]