On March 20 was Annie Leibovitz‘s installation session at the Académie des beaux-arts, here is her speech.

Speech by Annie Leibovitz

Sebastião Salgado

It is an honor to be in your company Sebastião. Thank you.

You are a great man.

There is a universal truth in your photographs.

In his most recent work, Sebastião Salgado turned to nature as a subject—to places untouched by humans. “I am pessimistic about humankind,” he said. “But optimistic about the planet. The planet will recover.”

Greeting to those in attendance

Honorable members of the Académie.

My friends, old and new.

And my family, who I’m so proud to have with me today.

We have four generations here. My mother’s sister Sally Jane and her children and grandchildren and two of my sisters, Susan and Barbara, and my brother Philip and their children and grandchildren. My daughter Susan is here. My oldest daughter, Sarah, is somewhere in the Appenine Mountains, studying limestone outcroppings. She is a young earth scientist.

Forgive me for not speaking French. My dear friend Dominque Bourgois has agreed to translate. Dominique and her husband Christian created a French family for me many years ago.

Thank you for welcoming me to the Académie.

I’m deeply grateful to be with you. It is profoundly humbling. It is honestly one of the great honors of my life.

I. M. Pei

You have put me in the company of so many wonderful artists, past and present. What makes this especially meaningful is that photography is represented in the

Académie alongside painting, sculpture, printmaking, cinema, dance, music, and architecture.

The great modernist architect I. M. Pei held the seat I am now taking. Beatrice Pei is here with us today. I. M. Pei’s daughter-in-law.

What I. M. Pei did was controversial before it was acknowledged to be monumental, which is the story of much great art.

He lived to be 102. During his long life he designed skyscrapers and museums and concert halls and hospitals and housing complexes that were artfully balanced between the bold and the traditional. His first major project was the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library which was commissioned by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. He was relatively young and obscure then. Other candidates for the job were much more well-known— Mies van der Rohe, Louis Kahn, Philip Johnson. But I. M. Pei was irresistibly persuasive.

He was known for his cultural refinement, his elegance, his taste. He was a cosmopolitan figure. He collected Abstract Expressionist paintings and Ming dynasty ceramics. He took on projects well into his eighties, including Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art. He traveled for six months on a journey to learn about Islamic architecture and history.

I. M. Pei was born in Canton, China, in 1917, and moved to the United States to study architecture at MIT and Harvard. He was based in America and worked all over the world. He was a revered master of international architecture. When he won the Pritzker Prize in 1983 he used the prize money to start a program to help young Chinese architects study in the United States.

His most famous creation, of course, was the modernization and expansion of the Louvre in the 1980s, with the geometrically precise and logistically brilliant glass-and- steel pyramid in the courtyard.

I. M. Pei made an indelible mark on Paris.

Paris / Cartier-Bresson

I visited Paris for the first time when I was a young photography student.

I had my first camera with me. I remember standing on the pedestrian bridge in front of where we are now, thrilled that I had discovered where Henri Cartier-Bresson had stood, where he had made a picture. Cartier-Bresson’s work made me want to become a photographer.

Susan Sontag liked to tell me the story of her portrait session with Cartier-Bresson. She was living in Paris, in a third-floor walk-up apartment on the Left Bank. She remembered Cartier-Bresson bounding up the stairs. It was 1972 and he was in his mid sixties. Susan sat on a couch with a coat wrapped around her because the apartment had no heat. Cartier-Bresson sat on a chair opposite her with his camera in his lap. They talked for a few minutes and every now and then she would hear a click. He never brought the camera to his eye. It was always in his lap. They must have sat there talking for ten minutes or so and then he stood up and said, “OK. So let’s have lunch.”

Susan was photographed by other great photographers, but Cartier-Bresson’s portrait is one of the most beautiful. He got her intelligence and charisma.

Susan/Photographer’s Life

Susan Sontag shaped my relationship to Paris—and to French culture and art. I wouldn’t be in this room if it weren’t for Susan. She loved France. French culture was central to her life as a writer.

Susan used to complain that I didn’t take enough pictures. She would say that every other photographer she knew took pictures all the time.

After Susan died, I found so many photographs I didn’t remember or perhaps had not even seen before.

I’ve made a point of editing my work from time to time and I’ve made many books over the years.

I love photography books. I collect them. One of my favorites is Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s Diary of a Century. It was designed by Bea Feitler, who edited it with Richard Avedon. I was lucky enough to work with Bea. She taught me that it is important to look back at your work. It is the way you find your way forward.

I began working on a book of the photographs I had taken between 1990 and 2005 and I realized that the years it covered were almost exactly the time I was with Susan. My father died not long after Susan did. My children were born during that time too—first Sarah and then Susan and Samuelle.

I called the book A Photographer’s Life. It gave me a better understanding of who I am as a photographer. A Photographer’s Life is the closest thing to who I am that I’ve ever done. It made me understand that my work is not one thing or another.

It is one thing.

Susan, my family, my children, my assignment work.

I thought that we could look back at A Photographer’s Life today.

Petra

Photographs take on new meanings after someone dies. When I made the picture of Susan at the entrance to Petra, the ancient city in southern Jordan,

I wanted her figure to give a sense of scale. But now I think of it as reflecting how much the world beckoned Susan. She was so curious, with a tremendous appetite for experience and a need for adventure.

You get to Petra by going through a long, narrow sandstone gorge that opens up suddenly to a view of a huge classical façade carved into a cliff. It’s spectacular, with enormous columns and friezes. That’s where Susan is standing. She loved art, architecture, history, travel, surprises. Discovery. She knew so much, but she always wanted to find out about something that she didn’t know before. And if you were lucky, you were with her when that happened

Family

Most of the photographs of my family were taken at gatherings around a dining table or a pool or beside the ocean. My mother had grown up in Brooklyn but she spent every summer as a child at the Jersey shore, swimming in the ocean.

My father was in the military when we were children (there were six of us) and every time he was transferred to a new base the family would get into our car and drive. We must have moved at least eight times. We didn’t have much money.

We didn’t stay in motels. We lived together in cars. My sister Susan says that the car window was my first frame.

After my father retired, he built houses. My parents lived in a suburb of Maryland in a house my father built. My father built my mother a small house on the beach. They always had a house on or near the beach.

My father lived for our family. So did my mother, but I think she may have had other ambitions. She had studied dance and she played the piano.

Susan and Pyramids

You would go into a museum with Susan and she would see something she liked and she’d make you stand exactly where she stood when she looked at it, so that you could see what she was seeing. You couldn’t stand a little to the left or a little to the right. You had to stand exactly where she had stood.

We saw a lot of the world. Susan and I climbed the pyramids. We went to places I would never have gone by myself.

Sarajevo

In 1993, when the Serbs lay siege to Sarajevo, Susan directed a production of Waiting for Godot with local actors in a bombed-out theater. Susan would return to Sarajevo many times during the siege. This meant a great deal to the people who lived there. She would be made an honorary citizen of Sarajevo. The plaza in front of the national theater is named after her.

Magazine Photography

I started out as a young photographer schooled in the fine arts. You took a photograph when you felt moved to. In the early 1970s, I was fortunate enough to be part of a magazine, Rolling Stone, where I was taken seriously. As seriously as a girl who worked at a magazine in the 1970s could be taken. I understood that what I did mattered. My life flowed from one assignment to another. I used to photograph rock and roll concerts and I would never hear the music. It took everything I had just to look through the camera.

Many of my favorite pictures were taken early on, when I was doing reportage, but I was never able to go back to reportage in a completely pure way.

I had learned too much. Too much about how a picture can be set up, how you can manipulate a picture, when it should be taken.

I’m not a journalist. A journalist doesn’t take sides and I don’t want to go through life like that. I have a more powerful voice as a photographer if I express a point of view.

Portraiture gave me the latitude to pick a side, have an opinion, be conceptual, and still tell stories.

Rhinebeck, Mother’s Portrait

My mother and father took photographs and made eight-millimeter home movies when I was growing up. We all had to smile and look happy in family pictures, even in the worst times.

My mother was in her seventies when I made a portrait of her for Women, a book that Susan and I worked on together. It was a tough shoot because my mother was nervous. She said she was worried about looking old. I wanted her age to show in the picture. Of course she didn’t like it. My father didn’t like it. He said that she wasn’t smiling.

I had always thought of the land I found in the Hudson Valley in upstate New York, along the river, as a gathering place for my family. I made the portrait of my mother there. When I bought it, raccoons were living in a small eighteenth-century farm house next to a pond. We restored that first and Susan and I lived there while the cottage in the main complex was being worked on. When we could move into the cottage, she used the pond house to write in. It became hers.

Susan’s illness

When Susan was treated for cancer in 1998, I took a month or two off from work and spent every day with her.

Paris apt.

We started looking for a place to live in Paris. I had been doing work in Paris for Vogue, for Anna Wintour, and I was thinking about having a child. Susan had lived in Paris off and on since the Sixties and had spoken often about living there again. She liked to come to Paris to write. It was hard for her to write in New York.

We found an apartment on the Quai des Grands Augustins. You could see the Place Dauphine and the spire of Sainte-Chapelle through a series of tall French doors that opened out to the Seine. In the seventeenth century it had been a printing shop. It was a wreck and it needed a lot of work.

Atget had photographed our building. Brassai had photographed our street at night. Picasso had painted Guernica around the corner.

Sarah born

A few weeks after 9/11, my daughter Sarah was born.

Susan’s death

Susan’s last illness was harrowing. I didn’t take any pictures of her at all until the end.

I forced myself to take pictures of her last days. I didn’t analyze it.

I just knew I had to do it.

The dress Susan was buried in is a Fortuny. We found it in Milan.

She had two of them, one in gold and one in olive green. The scarves were from Venice. The black velvet coat was one that she wore to the theater.

My father died a few weeks after Susan did.

Daughters born

That spring, Susan and Samuelle were born.

Susan

Susan is buried here in Paris, in Montparnasse.

End

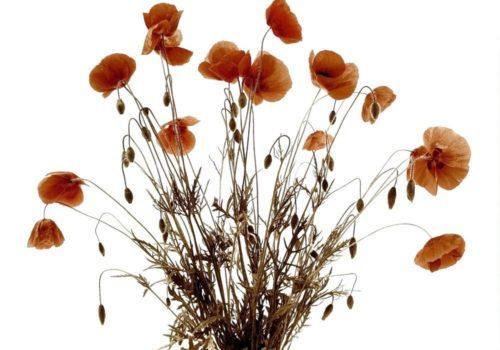

For me, photography represents life itself.

With a camera, we can retain the vanishing moments of our lives—our children, who grow up and change so quickly, the people we love and learn from.

Photography has always had an incredible power to stop and hold onto the present before it disappears into the past.

Is photography less special now that anyone can take a picture? That millions are made every second?

The truth is that photography was created precisely so that anyone could make an image of themselves or their families and friends or the landscapes and views and things that were meaningful to them.

The power of photography is the power to share our experiences with others across differences of time and geography and education and belief. To bear witness. The power to show what otherwise might not be believed. The power to stop and hold onto the moments that rush by us.

That so many hold this power in their hands, so many more than ever before, is the greatness of photography.

So that in understanding others, we might come to know ourselves.

I truly believe that this honor you’ve given me today expresses the conviction that even though it is changing, the photograph is more relevant, and has more force in our lives, than ever before.

Thank you.

Annie Leibovitz

Académie des beaux-arts

23, quai de Conti – 75006 Paris

www.academiedesbeauxarts.fr