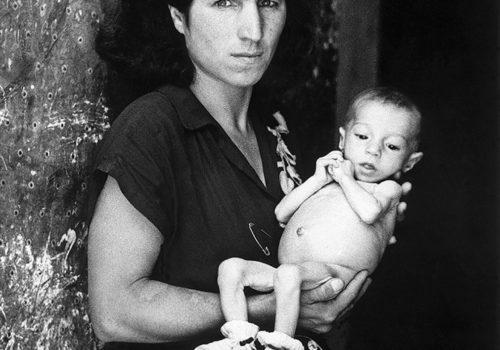

The new book "Inge Morath: An Illustrated Biography" by Linda Gordon is co-published by Magnum Foundation and Prestel, here is an excerpt.

Morath had dreamed of photographing along Marco Polo’s Silk Road route, starting from Venice. She broached this to Holiday without success,so she compromised. She knew that Robert Delpire was interested in a book on Iran, and Holiday went along with that.[i]Three commissions—from Holiday, Standard Oil, and Pepsi Cola—paid for the trip (“pure greed, but necessary,” she wrote her parents). In return, the latter two sponsors would receive photographs of their Iranian operations for use in corporate publicity. Holiday’s idea of showing Iran was laughable: mosques and carpets, of which the editor wrote, “A color photo of one of these masterpieces … might do it for this part of the Near East.” Morath’s agenda was far more ambitious—and knowledgeable, since she prepared for this trip by reading extensively about Iran and its culture.

In March 1956 Morath and Delpire took off for Teheran, on her “longest and most exciting trip so far.” She returned only when she ran out of film, propelled as always by irrepressible curiosity to press on to every new location, society, and culture she heard about. This trip lasted six weeks and it shows particularly vividly her fascination with–and respect for–foreign cultures.

(…)

Morath acknowledged her lack of enthusiasm for the industrial photography that her sponsors required. Unlike many earlier documentary photographers, such as Margaret Bourke White, she did not see beauty in industrial or “mechanical” forms, and was far more interested in the country’s natural beauty and rural people. She did, however, illustrate the contradictions of a modernizing Iran: between a state of the art Pepsi Cola bottling factory and vast oil refineries on the one hand, nomads living in tents with their camels and a mud caravanserai in the desert on the other. This is precisely what Morath meant by the title of her first Iran book, De la Perse à l’Iran, From Persia to Iran, from the traditional to the modern. Yet when the work was published, texts by others supplied the orientalist spin that Morath so scrupulously avoided. Alan Moorehead wrote in Holiday that he found Iran’s modernity “repulsive” and longed for the exotic “whiff of the lazy Arabic East.”

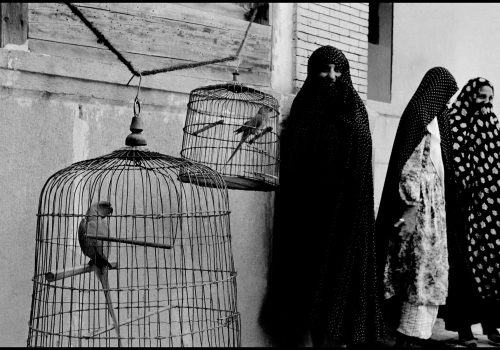

(Holiday did not seem to have registered that Iranians are not Arabs.) . Edouard Sablier, the French journalist who introduced a second, posthumous book, longed for “the glimpse of dark eyes beneath a deftly fastened veil.” Such commentary shows by contrast the respect and lack of sentimentality in Morath’s work. The photographs show no laziness, and the veiled women look forthrightly at the photographer. She did comment critically on veiling, in a photograph showing three veiled Muslim women next to caged cockatoos with a caption explaining that they were the wives of one man.

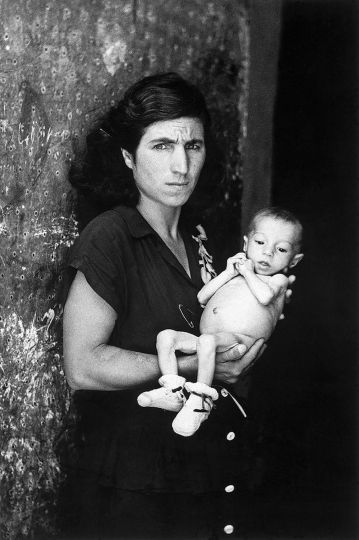

In Vanak, an Armenian neighborhood of Teheran, the interior of a small Orthodox church is decorated with rugs, chandeliers, candlesticks and lace cloths. In Zoroastrian villages, where people practiced a pre-Islamic Persian religion, she photographed the interior of a domed mud-brick home, with seats created by cutting out ledges in the walls. She centered here a framed image of Jesus, complete with halo, hung on the wall amidst framed photos of family, no doubt calling attention to this show of ecumenism. In another Zoroastrian home, three seated inhabitants are studiously ignoring the photographer. They remind the viewer of why Morath made few portraits in Iran. Despite her extraordinary linguistic ability, she could not speak Farsi or any of Iran’s other languages, and she could not usually get close to subjects. In some photographs we see people not only keeping their distance but even their suspicion or resentment. The absence of portraiture characterizes all her photography in North Africa and the Levant, from Tunisia to Jordan; when two young women of Tunisia appear in close-up, the subject is their exotic costumes, not their individuality.

A technical problem ruined many of Morath’s black and white photographs. One camera had a light leak, and the disaster was all the worse because, lacking a lab in Iran, she did not realize the problem until she returned. Consequently, most of her photographs of Iran remained unseen until 2009, when the damaged negatives were scanned and re-touched by Steidl’s expert digital darkroom for the book Inge Morath: Iran. Fortunately the camera she was using with color film functioned perfectly, and the results showed the color sensibility of one who loved painting. She also had an early Polaroid model which she used to create photographic gifts for those interested.

Once outside Teheran, making these photographs required enduring considerable discomforts. At a Standard Oil refinery in Abadan, the air smelled like petroleum and the publicity man who accompanied her was “lazy and keen on gin” as well as “a fanatic Inshallah.” The hotels were often miserable, her clothes were dirty and she had no way to wash them, and she suffered from the heat, for which she hadn’t brought the right clothing. At times she wore chadors and veils—which of course made her even hotter–as a gesture of respect for Iranian culture, and possibly for her own protection; luckily her Armenian driver showed her how and when to wear them, saving her from some cultural gaffes. But she usually wore trousers. Someone, probably Delpire, photographed her at work in Persepolis, wearing pants, a voluminous wool coat and flat oxford shoes—clothes for working.

Never daunted by harsh conditions, Morath’s curiosity and sensitivity to beauty produced some of her best work, on a par with her Spanish photography. Leaving Teheran brought her to entirely different classes of people—peasants, shepherds, nomads, artisans, mullahs, small merchants—and sites—the bazaar, tent dwellings, baths, interiors, mosques, ancient ruins, factories, oil fields, festivals. If there was a trace of orientalism in the Spanish photography, there was none here.

She photographed people at work—spinning, dyeing, carpet-weaving and carpet-knotting, metal-working, brick-making, cobbling, cooking, baking, laundering, gathering wood, hauling, and in bottling plants, cotton mills, oil refineries. People at leisure–making music, dancing, drinking tea, smoking hookahs, smoking opium, celebrating holidays.

In Iran’s southern desert regions, near Chum, Yazd, and Pasargadae, she photographed nomads rather lovingly, perhaps because they presented picture-perfect subjects: women dressed in brilliant printed fabrics contrasting with black tents and multi-hued earth colors; elaborate head gear and multiple beads; children sitting on camels, children carrying lambs. Her color photography showed the minute variations in the colors of the earth, sand, and mud structures. The earth’s colors rhyme with those of camels, people’s skin, and men’s worn, faded clothing, and these are punctuated by the bright colors of women’s clothing. Together the colors give the viewer a glimpse of why so many love the desert’s In the Alborz mountains a shepherd who could pass for a Christian image of Jesus herds his sheep northward to the Caspian Sea.

Many images show young children at work, especially young girls sitting at looms and spinning wheels, both artisanal and industrial.[iii] Some commentators have seen these photographs of working children as critical of child labor, but in fact they contain no critique; they simply report. With neither judgment nor pity, her photographs offer instead an anthropological view of cultural and economic life in a foreign country. There is no implication that the children are unloved, neglected, or abused. They are children living in a world in which everyone among the poor must contribute to the family economy, something Morathseems to have understood.

Nothing in the photographs references theCIA/MI6-backed coup that had deposed the elected Prime Minister Mossadeq in 1953, after he sought to nationalize the oil industry and guarantee better wages and benefits for Iranian workers. And Morath’s photographs reflect only positively on her sponsor Standard Oil’s investments there, though the corporation supported and may have instigated that coup.

This silence results from choice, not ignorance; always studying diligently to learn about what she was to photograph, she read about the political situation in Iran before leaving.[iv] Photography critics Andrew Grundberg and Monika Faber criticized Morath’s for its “implicit abandonment of any moral position.”[v] But her choice of subjects, while reflecting her response to trauma, derived also from humility, from demurring to assume that she understood enough to judge.As in all her work, she was a visual ethnographer; she did not go near questions of justice or injustice.

Linda Gordon

Extract from “Inge Morath:An Illustrated Biography”

Co-published by The Magnum Foundation and Prestel

Inge Morath:An Illustrated Biography

Hardcover, 192 pages, 23,5 x 27,3 cm, 68 color illustrations, 114 b/w illustrations

ISBN: 978-3-7913-8201-2

$ 49.95* | £ 39.95* (* recommended retail price)

Publishing House: Prestel