In the hall of Rangoon Central Station, a large format print of an unlikely encounter between a diver and a whale overlooks the waiting room and intrigues travelers.

This is not a coincidence; the remarkable photo is one of the works exhibited in several public places in the city for the Yangon Photography Festival (YPF). For its 12th edition, the festival takes over new popular spaces where passiveness and idleness usually reign: the central station’s hall, and the Dala ferries and terminal.

A spectator dressed in a longyi, the traditional Burmese attire, stops for several minutes to contemplate this underwater photo by Franck Seguin. The man’s name is Khin Maung Lwin. Today a taxi driver, he remembers the time when he, too, saw this majestic animal aboard the cargo ships he repaired in the waters of the China Sea and the Gulf of Oman. “It’s good to put the photos in popular and busy places, so that we can get to know the festival. Many people are also interested in the issues it addresses, especially on our own country “, explains the man in a satisfied tone.

In twelve years, the YPF has become Southeast Asia’s most popular photo festival, with more than 900,000 spectators this year. The works of local and international photographers are in the spotlight, exhibited for almost a month in galleries, institutions and public places open to all.

A festival for advocacy that takes over public places

On this occasion the Maha Bandula, the city’s main park, transforms into an open-air museum. It displays the World Press Photo 2019 traveling exhibition, images of young Asian photographers like the Indonesian Dwinda Nur Oceani for her series “To wear a hijab or not? ”, as well as two American and Burmese works, respectively by Lewis Hine and Ye Naing & Yan Moe Naing, on child labor. A century and thousands of kilometers separate these two testimonies, one depicting American children working in a chain in factories at the beginning of the 20th century, and the other revealing the current survival of young Burmese people carrying bricks. However, their combination appears necessary as an answer to those believe child labor is inevitable in some countries. Through the themes it showcases, the YPF stands out as a festival dedicated to advocacy.

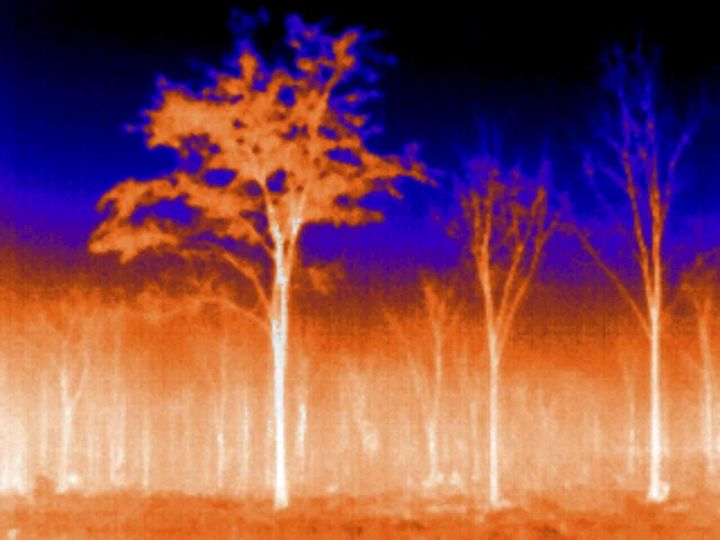

Pascal Maître’s “Baobabs”, exhibited around the lawns of the park, fascinate both the youth and the elderly. These impressive prints, several meters wide, attract crowds. Some are wearing thanaka, a traditional yellow vegetable paste used as makeup, others wear an anti-coronavirus mask: but all are ready to take selfies to immortalize themselves in front of these African trees. A plea for environmental protection stands behind this curious interaction with the image of a distant jungle world.

Lin Lin Tun, a fan of the festival, is particularly sensitive to this idea. Posing in front of these gigantic trees, he explains: “This is the fifth time that I have come to the YPF. I attend because it is, above all, a source of knowledge. Look at these trees. I come from Yangon (a highly jammed capital), and it carries me far into the forest.

For Pascal Maître, the author of the series, observing passers-by interacting with the photographs is very touching: “especially when exhibiting in large format, we always have the feeling that it is something that does not belong to us. And here even more because people are really immersed in the experience.”

Darkness falls on the Maha Bandula park; the buzz of the city gives way to the whispers of discussions, the echoes of laughter and the sound of children running on the lawns. These are packed with people sitting in small groups. The Yangooners enjoy a friendly moment to chat or share a meal. Tonight, images from the entire world keep them company.

Suddenly the whispers fade. Christophe Loviny, the festival’s founder and artistic director, takes the microphone in front of giant screen where hundreds of spectators are gathered. The YPF projections begin at twilight under the audience’s eager eye. An evening full of local and international photo stories can then begin.

Democratize and break codes

Thanks to a distinctive philosophy, Burmese photographers are at the forefront of the festival. Because, beyond being open to all, the YPF is devoted to training, exhibiting and rewarding the first generations of Burmese photographers.

“It’s a festival that has depth,” said Pascal Maître, referring to the YPF’s social and educational long-term commitment.

Through its organization PhotoDoc, the festival has become a vector for talent development. Each year, by holding workshops across the country, it trains young Burmese in photography for free.

“In the last twelve years, we have trained more than a thousand young Burmese men and women from all backgrounds, religions, and ethnicities to produce short documentaries about the most important social and environmental issues affecting their lives,” explains Christophe Loviny.

This year, the focus is on refugees with disabilities from internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, as well as on young students from Mandalay, the country’s second largest city.

Mizumi, a young teenager from the Lisu ethnic group with Down syndrome, depicts her daily life in a refugee camp through photography. Her testimony, which moved the public as well as the festival’s jury, won the 2nd prize for emerging photographers. The YPF, in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), establishes photography as an effective medium for communication and therapy by training IDPs with disabilities to produce work reflecting their daily lives.

There is something remarkably unusual about the YPF: it exhibits famous photographers alongside amateurs, who, for some, have only discovered photography recently.

This is particularly the case for the Mandalan student Ei Ei Phyo Lwin, winner of the 4th prize for emerging photographers. She explains that, until joining the YPF training, she used to take photos with her mobile phone only. Ten days after this training, she submitted her first photo story captured with a reflex camera lent for the occasion. Beyond the technique, it is learning how to tell stories with images that she recalls most.

Naw Phyo Phyo Zaw, her classmate whose work was screened at the Maha Bandula, adds: “Today in Burma, it is difficult to talk about important subjects such as the environment or AIDS. People are not very interested in it, so photography is an effective and powerful way to address these issues. ”

For these young photographers, the goal is to raise awareness about subjects dear to their hearts – and this, in a country still in the process of democratization. Nyan Lynn Aung, another student from Mandalay adds: “I wish society was more open and humane (…) People should be more compassionate towards minorities, rather than being trapped by religious doctrines. For me, photography is not only a means to show beauty, but also to denounce social problems.”

From photo journalism to contemporary photography

Hossein and Hassan Rowshanbakht, who exhibit for the first time outside their native Iranian borders, share the same philosophy. Through photographs of the billboards’ backside in the city of Kashan, the two twins mourn humanity’s thirst to modernize the environment. “Billboards are popping up all over the city regardless of the impact they will have on the landscape. The fact they can only be read from one side could also suggest their neglect for the life behind them”, they explain.

These conceptual images, filled with poetry, illustrate the festival’s diversity which merges different types of documentary photography – sometimes including contemporary photography.

As such, French artist Isabelle Ha Eav, transposes gold leaves and uses the bichromate gum technique on her silver prints for the exhibition “Irrawady”. For this series retracing life around the Burmese river, she explains that her artistic gestures stem from an ecological observation: “it was necessary for me, working with the river as the primary subject, to be aware of the issues surrounding and threatening it.”

A growing family

Before being exhibited at the Goethe Institute, alongside Belgian artist Stéphane Noël, Isabelle Ha Eav was an intern at the festival three years ago. Going back to Yangon feels like reuniting with friends. Old faces mix with new ones: each year Burmese and international volunteers or photographers participate in this collective adventure.

“I am always amazed by the opportunity to share that this festival brings about. Several subjectivities are shown, but, in the end, the YPF is a very collective experience. We meet, we observe, we talk and above all, we build together,” says the young photographer.

And it may be this precise feeling, the one of belonging to a big family, which makes the YPF experience truly remarkable. During the opening week, everything was done to enable social interaction with a succession of round tables, guided tours, dinners and joyful evenings.

It is impossible to depict the spirit of this YPF edition without mentioning the festivities that mark each night of the opening week. Young photographers, volunteers, and major figures in documentary photography celebrate together on the dance floor, in a karaoke bar, or even on the deck of a boat rented for the occasion. Paula Bronstein, a major figure amongst women photojournalists, grooves to the rhythm of rock songs, while young Burmese hold hands and sing loudly. Anecdotes, contacts and dance moves are exchanged amidst laughter.

Finally, we will remember the words of Hossein Farmani, historical sponsor of the festival and founder of the Lucie foundation. During the projections at the Maha Bandula park, he reminds the audience that the YPF is a place to create great friendships: “I encourage every Burmese photographer to adopt a foreign photographer, and to build a friendship with him over time. Together, we form an extended family across borders,” he concludes.

And it’s a winning bet. Year after year, the YPF builds a loyal audience gathering around the very essence of photography : unveiling our shared humanity.

Yangon Photo Festival

February 19th to March 21st 2020

www.facebook.com/yangonphotofestival

The photo-stories can be viewed on the « MyanmarStories » Facebook Page

Aline Deschamps and Paul Fargues are freelance photojournalists based in Beirut, Lebanon.