Archives 2017

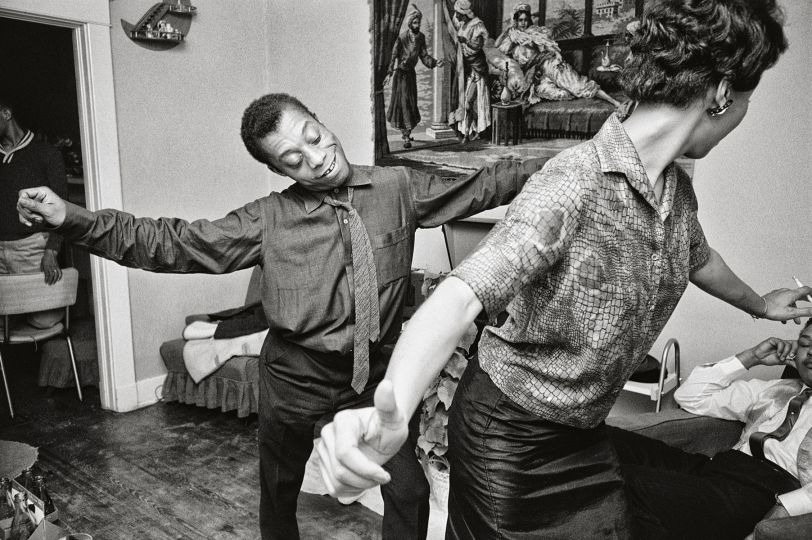

First published in 1963, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time stabbed at the heart of America’s so-called “Negro problem.” As remarkable for its masterful prose as it is for its frank and personal account of the black experience in the United States, it is considered one of the most passionate and influential explorations of 1960s race relations, weaving thematic threads of love, faith, and family into a candid assault on the hypocrisy of the “land of the free.” It is now republished by Taschen with more than a hundred photographs by Steve Schapiro who writes:

I arrived in Jackson in June of 1964 to cover the Mississippi Summer Project for Life magazine with John Gregory, a local stringer assigned to cover the story with me. John, a recent graduate from Ole Miss had lived in the South his entire life. He took one look at my appearance and immediately dragged me into the nearest barbershop—I looked like a New Yorker, he said, which I was. He told the barber I had lost a bet and needed a Marine haircut. He bought me a red shirt with an alligator logo on it, a pair of white corduroy pants, and a transistor radio case to hide my camera. Only then did he feel he could walk with me around town.

By that time, the civil rights movement had already experienced much, and I had already photographed the aftermath of the bombing in Birmingham, CORE activities in Clarksdale, and the March on Washington. Gregory and I had just come from Canton, Ohio, where we’d been at the training session for the Mississippi Voter Registration Drive organized by Bob Moses. Students and clergy, Black and white, from the North and the South came together to vigorously train for what they might encounter when attempting to organize residents in small Mississippi towns to register to vote. At the time, Mississippi had the lowest number of registered African American voter, and like the rest of the Southern states was highly resistant to change, there were all kinds of racist voting clauses in place with Jim Crow. The threat of violent reprisal toward any person who attempted to register Black voters was promised; animosity from the segregationists was high. The attitude in town toward outsiders was extremely antagonistic: Why are you mixing in our ways? You’re the ones who are the outsiders; you’re the ones who are causing trouble here.

During the final days of the training sessions, it was discovered that three civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, had disappeared while traveling near Philadelphia, Mississippi, they would later be found dead. Gregory and I had already left Ohio for Mississippi to investigate the burning of a Black church near that same town; so we were close by when we heard the news. I was the first photographer to arrive in Philadelphia when we stopped near the quaint town square. I saw this big burly sheriff and started photographing him. He strutted slowly towards me, then snatched the camera out of my hands. He opened the back, pulled out the roll of exposed film, threw it to the ground, and handed me back my camera. At the time, I didn’t know how lucky I was, the man was the notorious Sheriff Rainey, one of the leaders involved in the murders of the civil rights workers.

Because two of the three men killed were white, the press picked up the story big time. Suddenly the divide between two different cultures was obvious: the segregationists who would take up violence to maintain their way of life and those working for change who practiced non-violence to overthrow Jim Crow.

Maybe because I was with Life or maybe because Gregory was a local, we were followed by white supremacists groups like the Mississippi Sovereignty [check that this is what it was called] but were never actually threatened or harmed. We were careful too. When we visited a small storefront CORE office near Jackson, Gregory would drop me off and go park the car in the cemetery. When I was through, I would walkie-talkie him to come pick me up, and we’d quickly get out of town. Because we were press, and because we were white we were often called on to investigate a situation or find out someone’s condition in a hospital when the organizers felt they couldn’t.

Photojournalism did make a difference in bringing attention to the civil rights movement and in helping to change attitudes around the country. Charles Moore’s photographs from Birmingham are the best examples I can think of, his powerful images of Black protesters being chased by dogs and fired on with hoses. Those photographs not only brought awareness to the injustice of it all; they made people feel the injustice. Of course, at the time I didn’t think about history. “All the film I shot during the day would go on American Airlines baggage to New York to the Life lab. They would process it. Someone would make little circular clips in the sprockets of the film if they felt the picture was worth printing and that was about it. I was just hoping the pictures I shot that day would appear in next week’s issue, not thinking about where they would be in fifty years.

The first time I photographed Dr. Martin Luther King, I was not aware that he was going to be one of the most important people of our time. It was impossible to know that at the time. It was just the start of something. And that happens a lot, you’re not aware of the significance of something that you do because it’s just something that’s happening that day. It’s great to have hindsight, and to look back and even think of all the things that you did not photograph that you should have in terms of history. What I had the good fortune to experience in terms of the social and political development of our country, I couldn’t think of it at the time because there’s no way you can sense all of that in the moment. You are living it.

In the same way that you don’t know the scope of a story when you are in it, I didn’t know that when I read an article by James Baldwin in the New Yorker in November 1962 that he would lead me to photographing this incredibly important time. Baldwin introduced me to the civil rights movement; I read his article about the conditions of Blacks in America, which later became The Fire Next Time, and immediately called my editor at Life asking if I could do a photo essay on Baldwin. He struck me as someone who was particularly charismatic in the way he was influencing a very important subject. A month later, Jimmy was back from Paris and I started traveling with him on a speaking tour of the deep South.

In the course of four weeks, we traveled from Harlem to Mississippi with stops in Durham, North Carolina, and New Orleans. He introduced me to so many of the leaders of the movement. When we visited Medger Evers at his home, Evers went outside and put a towel over the license plate of our rental car, so the authorities wouldn’t be alerted to our movements. He did it only half jokingly; knowing full well that he was being watched and that the danger he was in was a reality. Later that Spring Evers was assassinated the morning after President Kennedy’s televised address on civil rights.

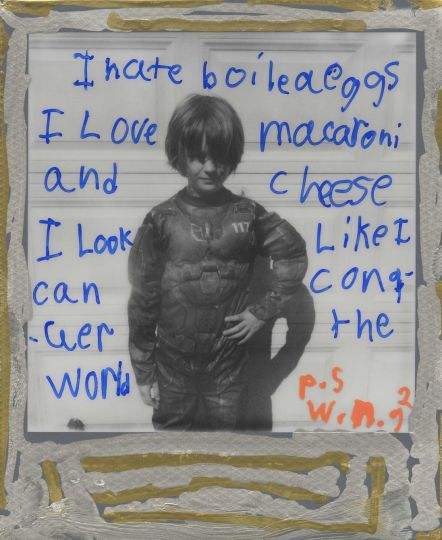

In Durham, Jimmy held an abandoned child in his arms, his appreciation of children always apparent. We ate fried chicken at JoJo’s in New Orleans and laughed a lot with other customers. On our journey, we saw poor kids who had no chance of being properly educated and people who were being intimidated against voting. We met liberals who were really not that liberal.

To me, Jimmy was plagued with personal sadness, and always seemed lonely. But he had a tremendous inner strength and brought that to everything he did, he was a force with which to be reckoned. His influence helped hasten the movement for the Black vote and school desegregation, and he helped to change the attitude of our government and the public toward civil rights reform. Here was a towering intellectual, a brilliant man, and Black leader, who never seemed to forget the importance of relating to each other as human beings. He had a hunger for love and believed in its power.

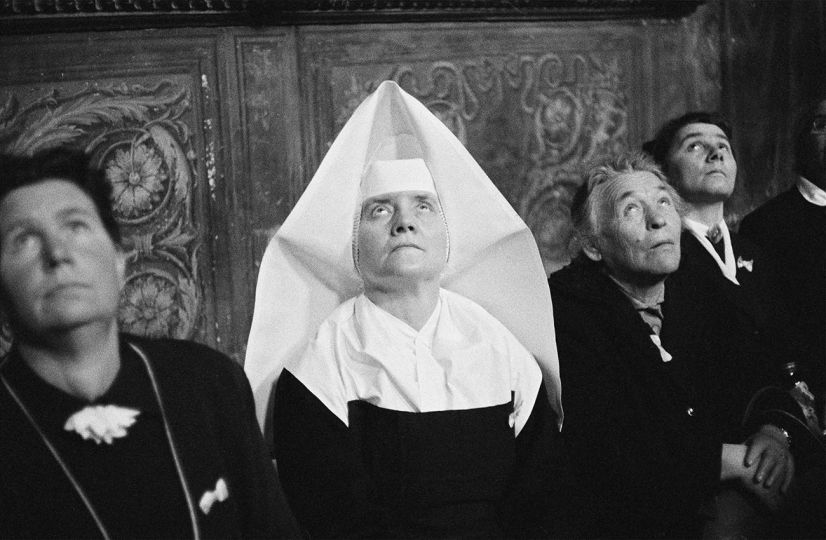

The attitude of the movement was church driven. The belief in nonviolence and the fundamental dignity of all human beings was exemplified at a drug store in North Carolina. A Black teenage girl pointed toward the local sheriff and said in the gentlest of voices, “That man, he caused me to spend 30 days in jail.” She said it without hate, retribution, or regret, but with pride. “

It was fitting then that the layout for my Life story included a photo of Baldwin at the pulpit. This photograph was on the right-hand page of the magazine, and as it went to press, it was discovered that on the left-hand page facing Jimmy was an ad for chocolate pudding. With great haste the editors pulled the Baldwin story from that issue. The story successfully ran a few weeks later, albeit without the church photo.

After the Baldwin story was published, Life and other magazines kept me busy photographing in the South. I covered many civil rights events such as George Wallace standing in the doorway at Tuscaloosa, the March on Washington, Jackie Robinson in Birmingham after the bombings, John Lewis in Clarksdale, and perhaps most importantly, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Selma March. As is the case for photojournalists, my work gave me a behind-the-scenes perspective. When Jimmy brought a group of Black leaders, intellectuals, and artists including Jerome Smith and Lorraine Hansbury to a meeting with Bobby Kennedy in 1963, they made it clear that President Kennedy was not doing enough to improve race relations. Bobby had expected to be applauded for his brother’s stand on civil rights, but Jerome Smith confronted him, saying, “This meeting nauseates me,” a sentiment backed up by the others. A month later, on June 11, 1963, unable to stand by as men, women and children participating in the movement faced imprisonment, violence, or worse, President Kennedy gave his landmark civil rights address on television, calling desegregation a moral issue “as old as the scripture.”

Jerome Smith also came to the March on Washington, which he felt was a failure because people came away exhilarated, feeling that the day was an enormous success. Jerome would have preferred that protesters had laid down on the train tracks and prevented everyone from going home, reminding them that the struggle was not yet won. And he was right, it wasn’t. There would be so many more deaths, so much more to achieve.

It was nearly two years later that that Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference successfully crossed the Edmund Pettis Bridge, the third and final attempt for protestors to walk the 54-mile highway from Selma, Alabama, to the capital of Montgomery in support of voting rights. The first two march attempts ended with state troopers battering the peaceful demonstrators with tear gas and clubs, the first, led by John Lewis, is known today as “Bloody Sunday” for the violent beatings that the protesters endured. The third attempt, led by Dr. King, wasn’t a heavily attended historical event like the March on Washington. It was only 300 people, who had to be protected by federal troops to march. But they did it, and four days later on March 25, 1965, thousands of people greeted them in Montgomery. National and international media covered the event, and the march garnered more support than any prior civil rights effort, leading directly to the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

As I was preparing for this book, I went back through my contact sheets from Selma, and was surprised to find I’d taken so many more pictures of Dr. King than I remembered. In many of the photographs, he seems to be looking into the crowd with concern, as if the many death threats he received daily might have credence at any moment.

These images of Dr. King have somberness despite the success of the Selma March, because in hindsight we know that those death threats would soon come true. When he was assassinated three years later, I received an assignment from Life to fly immediately to Memphis. When I got there, I first went to the rooming house where the shots had been fired. The assailant had apparently stood in the bathtub and leveled his gun on the windowsill, and I also saw this black handprint on the wall. I photographed everything, I photographed the handprint, and Life ran the photograph as a full page the next week.

Then I went to the Lorraine Motel and Josiah Williams, who was one of King’s aides, let me into King’s room. I saw the attaché case on the ledge, the rumpled shirts, and some Styrofoam coffee cups. Then his image suddenly appeared on the television set high on the wall. It struck me as a very symbolic moment. The physical man was gone forever, and here his material things still remained. And yet it felt like his spirit still hovered above us. That was one of the rare moments when I felt I was taking an important picture. I composed a shot with all those elements, the physical artifacts of the room. But Life never even clipped it on the contact sheet. Like I said earlier, you never know the importance of a photo at the moment you are taking it. Though Life didn’t think so at the time, I can’t look at that photograph today without a chill. A great man had just left, and I wanted to try to capture the loss. Impossible, of course.

Steve Schapiro

Steve Schapiro is an American photographer who lives in New York, USA.

James Baldwin & Steve Schapiro, The Fire Next Time

Published by Taschen

$200 (limited edition)

Steve Schapiro, Freedom Now

Civil Rights Photographs 1963-1968

Fahey/Klein Gallery

Los Angeles

http://www.faheykleingallery.com/