On February 19, 1942, a few weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese air force and the United States entry into the war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the arrest and detention of all people of Japanese origin, American citizens and legal residents alike. They would total 120,000. The exhibition Then They Came For Us at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York revisits what remains to this day one of the darkest chapters in American history.

This exhibition takes on particular significance at a time when political discourse is highly polarized, as it focuses on an event that many in the United States would like to forget, as it contradicts the image of the triumphant, just, and democratic America coming out of the Second World War.

The exhibition is organized chronologically and shows how the process of discrimination was implemented, the internment proper, followed by the opening of the camps after the war. It showcases photographs and other images of varied nature and origin, such as pictures by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, as well as Toyo Miyatake who was among the detainees. The exhibition further focuses on the different forms of resistance organized by the Japanese Americans before and during their internment.

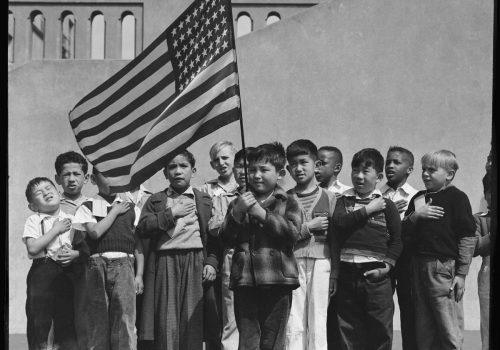

The show runs parallel to the Edmund Clark exhibition at the ICP, devoted to the secret CIA and Guantanamo Bay prisons, making a thematic comparison inevitable, given the proximity of their highly politicized content. Then They Came For Us explores the American temptation to sacrifice the rights of some people for the sake of the supposed security of others. It is astounding how the photographs showcased in the exhibition belie this idea of the other as a potential threat. We see, among others, men, women, and families that have nothing to do with this alleged threat and who, from the outset, appear rather as victims. The series of portraits by Ansel Adams, taken in one of the camps, met with contradictory critiques reflective of the spirit of the time: some saw them as too complacent in showing Japanese Americans as average citizens, while others thought they covered up the real living conditions of the detainees.

The exhibition comes at a point when America seems to believe less and less in its own illusions and fantasies. It could be said that Americans are increasingly sick of the classical propaganda portraying their country as a model democratic society. All the myths, in particular those pertaining to history, are being gradually revisited and debunked. The exhibition boldly foregrounds the inner contradictions of a country that liberated Europe from oppression even while choosing security over the respect of the rights of some of its citizens for racially motivated reasons. This is precisely what makes these two historical exhibitions so interesting: they are equally about the present.

Hugo Fortin

Hugo Fortin is a New York-based writer specializing in photography.

Then They Came for Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II

January 26 to May 6, 2018

International Center of Photography

250 Bowery

New York, NY 10012