When Western media announced the death of Alexei Navalny they shifted their attention to the lesser-known regions of the planet, such as the industrial cities and penal colonies of the Siberian Arctic Circle, here’s an unexpected archive concerning the town of Igarka.

Alexei Navalny was a prisoner at FKU IK-3 (ФКУ ИК-3) in the town of Kharp in the Priuralsky District in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, also known as Polar Wolf. Kharp was founded on August 21, 1961, on the former camp unit of the 501st Gulag construction site.

The Transpolar Mainline (Трансполярная магистраль, Transpolyarnaya Magistral) was a railway project in northern Siberia, a part of the Soviet Gulag system that took place from 1947 until Stalin’s death in 1953. Construction was coordinated through two separate Gulag projects: the 501 Railway starting on the River Ob and the 503 Railway starting on the River Yenisey. The present photographic archive documents the town of Igarka, the location of Gulag camp 503.

Igarka was founded in 1929 as a sawmill and timber-exporting port by the Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route.

Timber was logged in the basin of the Yenisei River, floated to Igarka where it was processed, and then exported to various distribution centers. The town grew rapidly as deportees during the dekulakization campaigns were sent to the camp in front of the town. Igarka was granted city status in 1931. The town’s construction was directed by Boris Lavrov, who envisioned Igarka as an ideal Soviet Arctic city. In 1939, the town reached its peak population of 23,648.

Further development was suspended due to World War II, but resumed in the late 1940s when Igarka became a naval port.

The town is located north of the Arctic Circle and is built on permafrost. Though it is situated inland, Igarka is a deep water port situated on the east bank of the Yenisei River and provides access to the Northern Sea Route. It located 673 kilometers (418 mi) from the Yenisei’s mouth.

Joseph Stalin announced the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class” on December 27, 1929: “Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes.”

The Politburo formalized the decision in a resolution on January 30, 1930. All kulaks were assigned to one of three categories:

- Those to be shot or imprisoned as decided by the local OGPU.

- Those to be sent to Siberia, the North, the Urals, or Kazakhstan, after confiscation of their property – including Igarka

- Those to be evicted from their houses and used in labor colonies within their own territories.

More than 1.8 million peasants were deported in 1930–1931. Those kulaks that were sent to Siberia and other unpopulated areas performed hard labor working in camps that would produce lumber, gold, coal, and many other resources that the Soviet Union needed for its rapid industrialization plans.

Joseph Stalin himself had spent the years 1913 to 1917 exiled in the area.

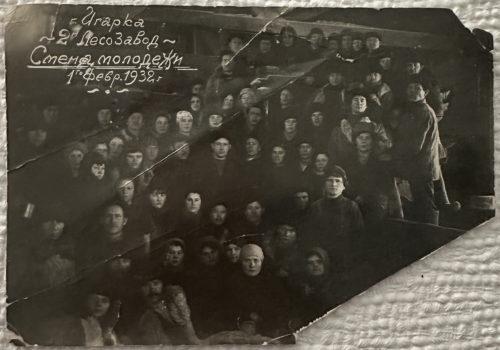

In this archive, preserved through the terrible years by Agnia K., the secretary of the Gorispolkom, Political Kommissar of the “free” city, there are only a few clues to the presence and suffering of tens of thousands of prisoners who passed through Igarka. The inhabitants of the free city resided on the left bank, while the prisoners were located in the labor camp in the Gulag on the right bank.

From 1949 to 1953, the Salekhard–Igarka Railway project made an unsuccessful attempt to connect Igarka to the Russian railway network at Salekhard, claiming the lives of thousands of Gulag prisoners.

The abbreviation GULAG (ГУЛАГ) stands for “Гла́ вное Управле́ ние исправи́ тельно- трудовы́ х ЛАГере́ й” (Main Directorate of Correctional Labour Camps).

KULAK (кула́ к, meaning ‘fist’ or ‘tight-fisted’), was the term used to describe peasants who owned over 8 acres (3.2 hectares) of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, kulak became a vague reference to property ownership among peasants who were considered hesitant allies of the Bolshevik Revolution.

The word ZEK originates as an abbreviation of the Russian term “заключённый каналоармеец” (zaklioutchonniï kanaloarmeyets), shortened to “з/к” (z/k), which literally means “detained canal soldier.”

Originally, the term ZEK referred to prisoners assigned to dig the White Sea Canal connecting the Baltic Sea to the White Sea. Subsequently, its usage expanded to refer to all prisoners of the GULAG.

Photo : The Secretary of the Political Kommissar, Agnia Krasnopevkova, in the office of the SeverStroy timber construction company in Igarka, 1931 – this company survived today in Eastern Siberia

Igarka was a town whose economy was dominated by a single industry: timber. The young Ispolkom political commissar, Agnia Krasnopevkova, assembled this photographic archive, with most photos taken during only two periods: 1931-1934 and 1960-1961.

The population of Igarka rapidly declined after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the closure of the main sawmill in 2000.

Photo : Anciferov, aborigine born before the revolution in old Igarka and reindeer herd, 1932

The district is home to most of the Ket people, a small and declining ethnic group whose language is thought by some linguists to be related to the Na-Dene languages of North American Indians. Nowadays, most of the people still speaking Ket live in just three localities: Kellog, Surgutikha, and Maduyka.

Photo : Office of A. Egorov, chief of the geocryological station, founded 1930 by the Academy of Sciences

In 1931, an underground permafrost research station was established in Igarka. Several shafts were excavated by hand in the late 1930s and early 1940s, extending as far as 14 meters into the permafrost. Research conducted in these facilities led to the development of building foundations specifically adapted to the permafrost.

Photo : Prisoners’ barracks on the right bank of the river, behind the cargo ship Vanzetti, Igarka, Summer 1932.

The photographic records of the Gulag system are extremely rare: Even within this archive, there are only four photographic prints that testify to the existence of the camp on the Right Bank of the Yenisei River. This is one of them, and the commissioner mentioned it on the back.

Photo : Igarka’s political commissar’s Secretary, Agnia Krasnopevkova, with the crew of the Vanzetti, 1931

Photo : In the summer of 1932, drought led to a sharp drop in water levels. The boat Vanzetti remained stranded, and the town management decided to build an open-water port, which was completed in 1935.

Photo : Dalgintsev, cargo ship Vanzetti’s radio telegrapher has just learned that he won’t be leaving …

This is probably the most moving photograph in the entire archive. The GorispolKom secretary has just recalled that the radio telegrapher – who stayed on long enough for the liner to run aground in the summer of 1932 – has been denounced.

Denounced! And now a prisoner, he’s off to join the kulaks, sent to the dreaded labor camp No. 503 on the right bank of the Yenisei River.

Photo : The few remarkable individual houses in Igarka and in particular the house of the head of the secret service, the dreaded OGPU

Photo : Important travelers come to Igarka by two-seater plane, such as Komsevmorput chief Boris Lavrov or OGPU representative Shoroshov, 1932

Photo : American model tractor, Oregon, transporting logs, Igarka, 1932

… “Enumerating these places, these holes, these worker villages, is almost equivalent to repeating the geography of the Archipelago. No camp zone can exist in isolation; there must be nearby a village of free citizens. Sometimes, this village, adjacent to some temporary logging camp, will last a number of years and disappear with it, and it will remain to sow the seeds for a later era. Even if some of these villages grew, giving rise to illustrious cities such as Magadan, Norilsk, Dudinka, Igarka, Temir-Tau, Balkhash, Dzhezkazgan, Angren, Tayshet, Bratsk, and Port-Soviet.

Some villages festered not only in wild backwoods but on the very trunk of Russia, near the mines of Donets and Tula, in the vicinity of peat bogs, near agricultural camps. Sometimes they are contaminated and blend into the world revolving around the camps for entire regions, like Tonchay. And when the camp is injected into the body of a large city, even Moscow, there is still a world around the camp, no longer formed by a particular village, but composed of people who, every God-given evening, leave it to spread out by bus or trolley and who converge back to it every morning (in this case, the contagion outward occurs at a rapid pace).” (Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, II, 2)

The Occident obtained a description of Igarka in 1937 through a curious propaganda article written by Austrian-born NKVD agent “Abo”:

…”I had heard much about the timber camps of Siberia five or six years ago when Russia began exporting at lower prices than Canada or Finland. Newspapers at that time wrote extensively about forced labor. I cannot speak to the conditions then. In Igarka, I found that of the fourteen thousand inhabitants, four thousand were exiled kulaks, formerly rich peasants who resisted the collectivization of their farms, either by actively sabotaging the work of the Collective or by resisting taxation, which was particularly high for private enterprise. Now they are paid normal wages for their work in Igarka, and outwardly can hardly be distinguished from the free workers. They live next door to them. There are no guards; none are needed. The nearest railway station is almost 1,500 miles away up the river… ” (Harry Peter Smollett, alias Hans Peter Smolka, The Economic Development of the Soviet Arctic, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 89, No. 4, Apr., 1937)

Construction of the Salekhard–Igarka Railway began in the summer of 1949 under the supervision of Colonel V.A. Barabanov. The 501st Labour Camp commenced work eastwards from Salekhard, while the 503rd Labour Camp pushed westwards from Igarka. Plans called for a single-track railway line with 28 stations and 106 sidings. Spanning the 2.3 km Ob River crossing and the 1.6 km wide Yenisei River crossing was not feasible. Ferries were utilized during the summer, while in the winter, trains crossed the river using a track laid on the ice, reinforced with specially strengthened crossties. It was estimated that anywhere from 80,000 to 120,000 laborers were engaged in the project.

Winter construction was impeded by severe cold, permafrost, and food shortages. In the summer, challenges included boggy terrain, diseases, and attacks by mosquitoes, gnats, midges, and horseflies. On the technical side, engineering hurdles included construction across permafrost, a deficient logistical system, tight deadlines, and a severe shortage of power machinery. Consequently, railway embankments slowly sunk into the marsh or were eroded by water pooling behind them. A scarcity of materials also impacted the project.

Photo : Igarka’s GorsipolKom secretary, Agnia Krasnopevkova, now retired, in her Moscow apartment, 1975, explaining and commenting on each of the photographs to ensure their transmission

Photo : Mimeographed list in Cyrillic with details and explanations provided by the Commissaire

After the death of Stalin in 1953, the Salekhard– Igarka Railway project was abandoned, and many deportees were allowed to return home. However, the town recovered, and by 1965, it was the second-largest lumber-exporting port in the Soviet Union. During this era, the town witnessed the construction of typical concrete housing blocks.

Photo : Igarka, Winter 1960

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the sawmill became economically non viable in the new free-market environment due to the high costs associated with harsh climate conditions and long distances to buyers. The sawmill closed in 2000, leading to a rapid decline in the town’s population. Increasing mean annual air temperatures resulted in permafrost thaw, which destabilized and structurally impaired many buildings in the town.

To reduce maintenance and utility costs of such buildings, the town demolished and controlled burned the historic district, mainly consisting of wooden houses, in the mid-2000s.

Approximately 4,000 residents were relocated to newer apartment blocks.