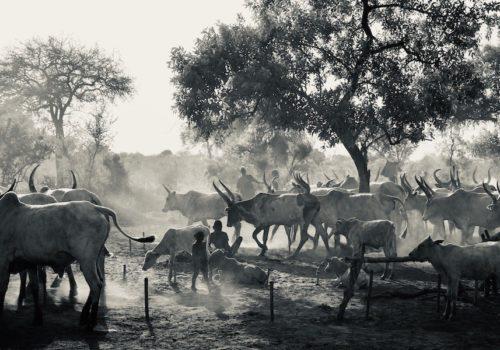

Cattle that mean the world to the Mundari

With 12 million cattle, South Sudan is the country with one of the highest cattle populations in Africa. The Ankole-Watusi cattle of the Mundari are considered the “kings of cattle” thanks to their imposing horns. To say that the Mundari love their cattle is an understatement. Their entire world revolves around them.

When I arrive at the camp, located in a clearing, in the afternoon after an hour-long drive through dense bush, I encounter tall young men and women, just ash-smeared boys and a few infants. No one is over mid-thirties. All of them smile at me curiously but friendly. The older Mundari live in villages loosely arranged from typical African round huts and grow sorghum, corn, peanuts and sesame in addition to raising livestock. The women distill liquor, which their men then consume in considerable quantities. However, I look in vain for cattle in the camp. They are out grazing during the day and return only shortly before sunset. According to the stakes they are tied to at night, there must be hundreds of them. Some boys are still busy picking up the cow dung and piling it into cone-shaped piles. The others present are sitting companionably together, willingly answering my questions or having their pictures taken.

The idle hustle and bustle ends abruptly when the first cattle appear at the edge of the forest. Everyone rushes to the stakes and waits there with the cords in their hands for each animal to find its place and willingly let itself be tied up. Although the stream of cows does not want to end, everything goes smoothly and without hectic. Afterwards, the men lovingly rub the hide and horns of their cattle with the ashes of last night’s dung fire. The ash, which is as fine as talcum powder and serves as an antiseptic, dusts the air peach-colored in the evening backlight. Occasionally, the sweeping curved horns of the favorite animal are also adorned with tassels that drive flies from their eyes with every movement. The owners proudly pose with their favorite and imitate the swing of the horns with their arms. In the meantime, the manure, which is accurately piled up into cones, is ignited and the smoke clouds rising in the setting, glowing red sun envelop the camp. The initially still warm light becomes increasingly colder. An unforgettable spectacle, which unfortunately is only of short duration.

The blue hour is used by the women and boys to milk the cows. Unasked I am offered the still warm milk to drink. It is creamy and tastes delicious. The darker it gets, the more clearly the flames and embers become visible and illuminate the heads of the cattle standing around them. Now the people also camp around the fire, either on simple wooden platforms or in the still warm ashes, talking or smoking shisha. They spend the night like their animals in the immediate vicinity of the fire, which protects them from mosquitoes.

At night, music played on horns resounds through the camp. People sing near the fires until they fall asleep under the starry sky next to their cattle. At dawn, when it is still pleasantly cool, the camp comes to life. At their morning toilet I notice the sometimes quite large twigs serving as toothbrushes and their way of showering: they put their head under the urine stream of a cow. The Mundari also drink it in the belief that cattle urine cleanses them internally. It is also popular among the men to dye their hair orange with the help of the ammonia in the urine. Afterwards, the skin of the cattle is again rubbed with ash, but now also their own upper body and head, in order to protect them from the heat of the scorching sun.

Before the boys – they are mostly naked – start collecting and piling up the cow dung that has accumulated during the night, they quench their thirst and hunger by drinking directly from the cows’ teats, just like the calves. A common practice of the Mundari to stimulate the cow’s milk production is to blow air into her vagina for minutes. Until adulthood, milk and yogurt are virtually the sole foods of the Mundari. Only on special occasions such as initiation rites, weddings or funerals is an animal slaughtered or milk mixed with blood.

The lantern-high poles painted black and white with cattle skulls attached to the top, which decorate the camps, bear witness to past initiation rites. The boys undergo the initiation rite at the age of 12 or 13. They go for several weeks to one of the village elders into the savannah, far away from the community, and are trained by him in fighting, dancing and singing. The initiation rite ends with a ceremony in which the boy cuts the throat of a bull. After that, he is allowed to call himself a man, wearing on his forehead the “V” symbolizing the horns of the cattle.

Now the boy has to prove himself as a man, be it in wrestling popular among the shepherds or through bravery in cattle raids or successfully fending off such raids. For it is important to have enough cattle in the next few years to be able to pay the bride price. This has more than doubled since the end of the war. In the past, the price was between 20 and 40 animals, but today it can be as high as 100. The value of a cow is estimated at an average of USD 300, thus a wedding costs between USD 10 and 30,000 in a country where 80% of the people get by on less than USD 1 a day. The reason for this inflation is that after the war many young men returned to their villages. The financial pressure on the young men is enormous. It is therefore not surprising that the number of cattle thefts in Southern Sudan has increased massively. Since cattle herders are no longer armed with spears but with Kalashnikovs, some 2,500 people die each year in South Sudan in cattle raids and the resulting reprisals.

For the bride’s parents, owning as many cattle as possible means high social standing and good retirement provisions. At the marriage, therefore, the value of cattle to the Mundari becomes particularly evident. They are a kind of “mobile bank account” that must be protected and increased, if necessary by force of arms. Besides the cattle, they have practically no material possessions. This becomes obvious when the Mundari break camp to find new pastures for their herd. The men have already left with the animals, the women pack up all the household goods in a single bundle, which they carry away on their heads with long strides.

Back in the village, I witness a funeral of a respected “chief”. More than a hundred mourners have arrived, some of them from the provincial capital with their leather-padded Land Cruiser and military escorts. All are feasted during two days, alcohol flows abundantly and the mourning chants do not stop during the night. A successor has to be chosen. After hours of palaver under a large mango tree, they have decided. His task will be to convince the families to move with a united herd in search of new pastures due to the ongoing drought, without encountering scattered rebels or landmines that have not yet been defused. He promises to take me to the new camp the next day. Unfortunately, nothing comes of it, because he first has to sleep off his drunkenness.

Holger Hoffmann

Holger Hoffmann sees himself as a travel photographer. So far, he has visited over 60 countries outside Europe. The longer he travels, the more he is fascinated by the customs and the daily life of indigenous peoples who have preserved their traditional culture. In his photo essays he tries to capture that.

For more details, please visit his web page on: www.chaostours.ch