A Letter to Hiroshi Watanabe From Elizabeth Avedon

Dear Hiroshi,

I received your beautiful book, “The Day The Dam Collapses.” I’m moved by both the images and the text. Actually I’m floored by the text. I relate to it in every way. You have put into words what everyone ignores each day while trying to control their lives and the lives of others around them. It is beyond Zen, even beyond Dharma taunting the principles of cosmic order.

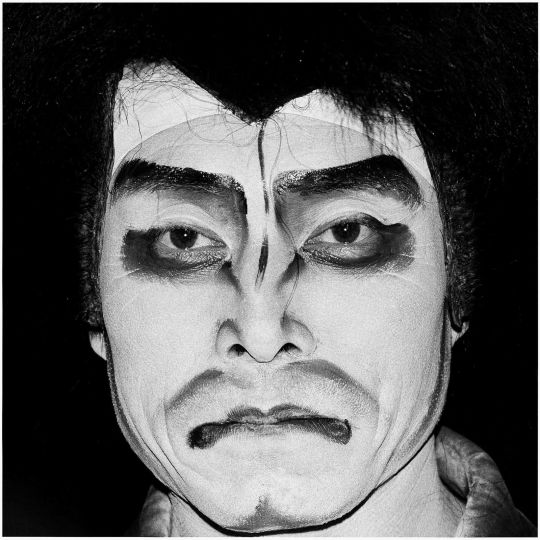

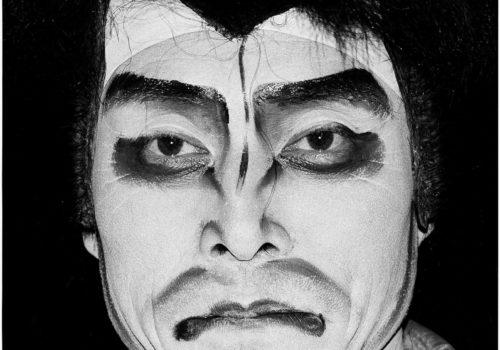

I’ve always been drawn to your work beginning with your series, Findings. Then I discovered your theatrical images of traditional Noh Masks of the Naito Clan, Kabuki Players, Ena Bunraku puppets, and later, Suo Sarumawashi, the “Monkey Dancing” portraits. You took a different turn in your series “Love Point,” photographing artificial Japanese Sex Dolls as models, along with almost identical live models.

And now the images in your new book balances somewhere between the real world and images pulled to form a single kigo. Please explain your point of view in this work.

Hiroshi Watanabe: I have been struggling to write my thoughts on the topic. Writing is always hard for me, but this time is harder. I am not sure if I put words together correctly .If I have to say succinctly what my point of view is in this book, it will be simply, “there is no point.” I don’t know what the truth is for sure, and you probably don’t know it for sure, either. But I am thinking about it, and thus I am curious. That is why I keep looking and I keep photographing. For me, fact/reality comes first and my point of view later. This approach of mine is probably the opposite of most artists’. Most artists start with ideas, convictions, or sometimes by divine afflatus, to create something. They have the talent and they have the intelligence; they have the goals and they lead others to the artists’ visions. They use art to convince others of their points of views. But I sometimes wonder–isn’t reality (things happening outside) much more surprising and more creative than one can conjure up in his/her mind? Isn’t the outside world more interesting and intriguing than their closed “originality”?

EA: What came first; your text, or your images?

HW: In my work, images always come first. I photograph what I am intrigued by–things that puzzle me and make me curious. Then I gather what I photographed and start thinking about the images–why I photographed them–why they are important to me, and so on….. then I edit them and put together a body of work. Only after that, I start working on text. It is always a struggle for me and I do it only to the extent that is necessary.

EA: Can you give an “artist statement” for these images if we had not read your essay?

HW: Can you use a small section of the text from the book instead?

“Disaster movies, like the ones with infernos, big earthquakes, or the arrival of aliens, often begin with depictions of normal daily life. For instance, we watch a mother trying to wake up a child, who resists getting up but then runs to school without having breakfast, while the mother shakes her head as her husband ignores the whole episode with his face buried in the newspaper. These mundane scenes are usually avoided in other types of movies, but they bear importance in disaster movies. The viewers know that what they are watching is a disaster movie, and so they sense these mundane scenes are in fact preludes to the terrible and unusual thing that will happen to the people on the screen.

What is important here is the fact that while the audience anticipates it, the movie characters do not know they may be involved in a huge, horrible disaster. The audience is in a sense like prophets looking down from above the clouds on the people who are living peacefully only because they are not aware of what is about to happen.

The truth is, we are all living like the characters in a disaster movie. We know we may some day face a disaster or a terrible event, but we keep living calmly because we do not know exactly what might occur and when it would be….”

“…someday I will be swallowed by the rush of the water from the broken dam and die happily, without knowing the true meaning of my life.” (Watanabe, Hiroshi. The Day the Dam Collapses. Daylight Books, Fall, 2014)

EA: Have your children influenced your observations in your life?

HW: I am almost hesitant to say this because it is such a cliché, but it is true that children teach parents much more than parents do children. Children are curious about everything around them and they see small details that we don’t see. This morning, my son stopped on the way to school, squatted down, and kept staring at a half-dried dying worm on the sidewalk until I told him that we had to go. I would never have noticed it if he didn’t make me stop and look. This sort of things happens all the time. In my book, there are many small lives dead or dying. I think I started noticing them because he opened my eyes.

EA: How did this book – as a whole – come about?

HW: Initially I did not mean to start this body of work. After my son was born 6 years ago, I could not carry my usual camera, a Hasselblad. Instead, I had to carry the baby along with diapers and bottles when we went out. I was also asked to take family pictures. So, I started to carry a small digital camera. And I stopped looking around for some time. But then I started to see things and I could not resist to photograph them. So, I used what I had–a small digital camera to record what I saw. For five years, I took pictures of things, without much intention, that I could not ignore. I saw and photographed many small lives, dead or dying. Later I found these images on my computer in between my happy pictures of my happy life. I gathered them and I started to think why I took those pictures. That was how it came about.

EA: You once told me over the phone when I worked at Photo-eye Gallery that you were either inspired by or influenced by Richard Avedon’s photographs.

HW: I remember talking about Richard Avedon with you. I’m not exaggerating if I say he is the biggest reason I got into photography. When I was in high school I saw the movie “Blow up” by Michelangelo Antonioni. The photographer in that movie was supposed to be modeled after David Bailey. I was young and I thought it was “cool” to be a fashion photographer. With that reason and with my way of avoiding the rigor of studying, I told my parents that I wanted to study photography in a university in Tokyo.

Richard Avedon was the most famous and coolest fashion photographer at that time, and I dreamed to be someone like him. That is why I came to the U.S. (although I went to L.A. instead of N.Y.). Years passed and I happened to be in N.Y. around the year 2000 when the Whitney Museum was doing a big exhibition of Richard Avedon’s work. There I saw his portrait work very closely and was amazed by the impact of those photographs. For the first time I felt like I was facing and staring at those famous people in person, as if I was just an inch away. Skin, wrinkles, eyeballs, hair, and expressions were there to see.

Strangely we always try not to see people’s faces much when we stand in front of them. It is not nice to stare at people. That is what we were taught. So, being able to stare at faces for a long time was a big surprise for me. With photography we can do that. Photography helps us to find, look, and study.

EA: Hiroshi, once again it was great talking with you. Thank you for your time.

All the best, Elizabeth.

BOOK

The Day the Dam Collapses

By Hiroshi Watanabe

Daylight Books, 2014. 88 pp., 66 color illustrations, 7½x9½”

Published in conjunction with Tosei-sha Publishing Co., Japan

http://www.hiroshiwatanabe.com

http://www.elizabethavedon.com

https://daylightbooks.org/