Inspired by the House heritage of travel, Louis Vuitton’s Fashion Eye collection evokes cities, regions or countries through the eyes of fashion photographers, from emerging talents to industry legends. Each title in the series includes a wide selection of large-format photographs, as well as biographical information and an interview with the photographer or a critical essay. After Louis Vuitton City Guides and Travel Books, this third collection presents travel photography from a fashion perspective, as the chosen photographers bring a unique vision of large cities, far-off lands or dream destinations.

Henry Clarke’s India is a lost city. The photographer’s trip for Vogue, supposed to dress the pages of December 1964, gives this issue a ticket to exoticism. He visited the site several times. At that time tourism takes a great inspiration, the territories are not all known and the appetite for the world is no longer reserved to great explorers. The evocations of elsewhere are editorial lines, and the photographers, missionaries of the far away, participate with large reportages to widen the confines. Henry Clarke’s approach is more suggestive. It says nothing or very little of the society of the time and contrasts with the different colors often accorded to this country: happy pigments, throbbing misery, friendly deities, demographic pulsations … It crystallizes all the same a meticulous orientalism, where suggestion disturb the imaginary. The search for empty and monumental spaces serves to fill everything a reader of the 60’s could expect. The sensuality of femme fatales, which are often thought of as spies or goddesses, architectural miracles, palace ornaments and some distant landscapes caress fantasies.The pretext of India becomes playground. A suitable decor.

The places are inhabited as autonomous museums. The city of Fatehpur-Sikri makes models appear as threatening guardians, ready to pounce or lurking in the shadows, with a forbidden side. In the palaces of Jag Mandir, Jaisamand or Jag Niwas, they are a support of the quality, sometimes bored princesses on small sofas, sometimes playful, dreaming transported by the statues of elephants. Posed as colorful offerings on the divine sculptures of the gallery of the gods in Jodhpur, they fix the lens as blasphemous, odious and intractable threats on their mother-of-pearl setting. The relationship to space becomes clearer, these places, often taken in close-ups, in detail, pursue India’s dotted line. It is a question of “tasting” delicious slices of enticing visions, a complex elsewhere that one seeks to portray through myth. India’s power emerges then, one presumes the civilization ancient, the obvious spirituality, a virtuosity in the techniques and landscapes, not quite Persian nor quite East Asia. The unique becomes more precise, made visible by women as beautiful as the place because simply graceful.

A slender woman supports with her bare arms one of the many columns of Mandore Garden. A turban also serves as a coat, hiding her breasts and buttocks. This is Henry Clarke’s method: playing with codes, extrapolated sensually. Models with iconic postures are dressed in colors that we imagine local, sexy wearing a turban, barefoot or sublimated with pearl shoes. Among the aesthetic references, there is pristine white quasi-colonial and some traditional revisited. Wreaths of flowers casually strewn in empty palaces as if the rituals had no time. This time is caught by these sophisticated clothes that move in ageless monuments. There are also postures most of the time contemplative, as to pay tribute to a decor that exceeds its functions. To take these shots like scenes, one imagines a film, Fritz Lang full color or Le Mépris exploded in latitudes. A total aestheticism, a mix of Greek and Egyptian positions that bring back one project: mystification.

These photos are really from the 60s. They have a fascinating kitschy side. With the eyes of the present, a contemporary allows him or herself to judge. Yet this feeling also questions the otherness. Be that as it may, the condemnation or the wonder of kitsch can not suffice as eyes on the world. Once the comfort of the eyes disturbed, one must know how to go further. This is what allows the perspective proposed by Sylvie Lécallier, publisher of the book. The golden faces of mannequins is justified. Henry Clarke’s suggestions about his dream India become more visible. And behind the scenes of these great travels that look like expeditions,help the understandinf of a public looking with fascination and caution towards the outside world. If the angle remains an artist’s choice, the reception is often a matter of context.

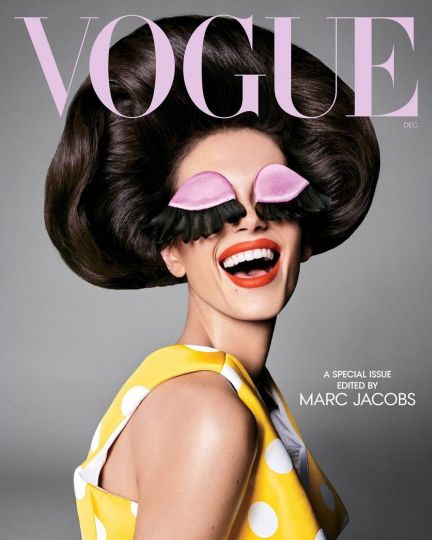

Finally, we must salute the ingenious and beautiful edition whose central pages reproduce, in a finer paper, the reportages published in Vogue. To keep your feet on the ground, the book opens and closes with photos of atmosphere and landscapes. The boundaries marker are laid, the crystallization delimited. By treating India with overpigmented colors, one would be almost astonished at the relative sensitivity of the tones. To remedy this, the back cover acts as a sun, quite captivating, that we would like to look in the eyes. The imaginary confronts reality.

Rémi Baille

Director of the publication of the magazine L’Allume-Feu.