In 1975, while working as a young journalist at PHOTO magazine, I had the privilege of interviewing Helmut. He was recovering from a heart attack in New York that had turned his life upside down. The conversation lasted hours. June was there, and we can never overestimate the importance of the role she played in their Parisian apartment on Rue Abriot. Thirty years later, not a single word needs to be changed.

Interview by Jean-Jacques Naudet, PHOTO, n°92, May 1975

Each photo by Helmut Newton is immediately recognizable by his signature setup, decor and atmosphere. Each series (for Vogue, Oui, Playboy, Marie-Claire or Nova) from this artist, who is German by birth , Australian by necessity and French by adoption, is a celebration of the imagination and the soul. Helmut Newton is currently the undisputed master of fashion and beauty photography. For proof of this title, look no further than his most recent exhibition at the Nikon galerie, which he prepared at the same time as the following portfolio.

This is an exhibition/retrospective of his images from the past two years, which are a brilliant abundance of eroticism, sensuality, provocation and ideas. A worshipper of “the world, the half world, the artificial and the superficial,” Helmut Newton is a complete, uncompromising character in full acceptance of himself. He gives a rare example of perfect accordance between fantasies and photography, which is a necessary tool, an absolute profession of faith and an essential support to the creative process. In the following interview, he bluntly enlightens us about his artistic approach.

Photo: For the past 2 years, you seemed to be in top form with a consistently increasing reputation. Is there an explanation to this growth?

Helmut Newton : Yes! I had a myocardial infarction on December 12th, 1971 in New York. This day, I suddenly fell on Park Avenue and woke up at the hospital half paralyzed, unable to speak or write. It’s useless to tell you when you come out of this experience alive you make several resolutions, but I radically changed my way of life and work down to the most precise details. I used to smoke 50 cigarettes a day and I haven’t had any since. I wasn’t acting my age, but as an unconscious young man. I quit all this craziness. One example: In September 1971, 3 months before my accident, I photographed the collections in Rome. I love this city. Twice a year, on this occasion, all the photographers from around the world gather there and party nonstop. Result: In 6 days I slept 18 hours and the following week in Paris, I played the same game. So when I left the hospital, I questioned everything. I needed to stop the useless work and unrestrained competitions! Today, I only photograph what brings me money and pleasure. I wouldn’t do it for anything else.

Photo: Is the infarction the reason that inspired the change in your images, particularly the birth of this violent and provocative eroticism?

H.N.: I think so. At the hospital, for the first time in my life, I took personal photos. During my recovery, I bought a small, compact camera with an electronic and automatic exposure. I was recording everything: the visitors, the nurses and doctors. It was maybe to take my attention away from the sickness. Never before had I made personal photos. From the wonderful travels and the beautiful models that I met, there was nothing left, not a single photo. After 10 days of uncertain prognosis, the doctor told me, “You will live, but be careful.” I promised myself to create all the images that I felt like shooting. The year following my infarction, I quit fashion and started doing nude portraits – only nude. Quickly, these appeared to me to be even more boring than the rags. I came back to fashion with enthusiasm, after acquiring a new experience with the nudes. For myself then, I started doing what I call “erotic portraits.” You have published some of these, including Charlotte Rampling and Suzie Weiss. These are nudes or semi-nudes always in black and white. Most of the models I asked to pose for me agreed. They trusted me. They knew that I would not show horrible things of them. I don’t say pornographic. However, pornography can be really beautiful. The photographs by Alan Jones are encompassed with pornography and are admirable. I am exasperated by the discrimination between eroticism and pornography. This reminds me of the opposition between good and bad taste. I hate good taste. This is a boring expression that makes everything suffocate. No! When I speak about horrible things, what I mean is: offense and disrespect towards the model.

Photo: What did this year long immersion in nude photography bring you?

HN: A new vision, a wider experience. It’s impossible to always take the same images, the same way that it bores you to death to work for the same paper. Today I get bored very quickly. I need to have fun shooting my images. To me, fashion is not an illustration, it’s a way to set up an idea. The real fashion, I mean haute couture, is dead, with two exceptions, Mrs. Gres and Saint-Laurent. I now refuse to cover the collections. Working six nights in a row from 1am to 7am to photograph four ugly and unwearable dresses, no thank you. Today, I have better things to do with my time. Prêt-a-porter is more fun – more inspired than the so-called haute couture. To come back on my experience with nudes, I think that I have learned how to integrate it into my fashion images. I don’t take pictures of 17-year-old girls with a beautiful body. I photograph young, 30-year-old women with imperfect bodies, but with interesting faces. To me, the eroticism is the face, not the erogenous parts. It’s an old cliché to assert that eroticism is the opposite of full nudity, but it’s so true!

Photo: You always take pictures of the same type of girl, the “society girl” stylish, ambiguous and perverse…

HN: To me, bourgeois women are more erotic than a hairdresser or a secretary. Nothing in these words is meant to be negative, it’s an observation. Class, elegance, education and sociological environments are factors I believe in. I sometimes feel guilty about it, but that’s the way it is. A bourgeois woman is naturally sexy. I hate when everything is exhibited in the window – it feels cheap. On the contrary, I love when you have to dig inside. I love communicating the idea that the women I show are accessible. They are actually. Their accessibility only depends on the time and money you want to spend…

Photo: To summarize, today you place your fantasies in your images.

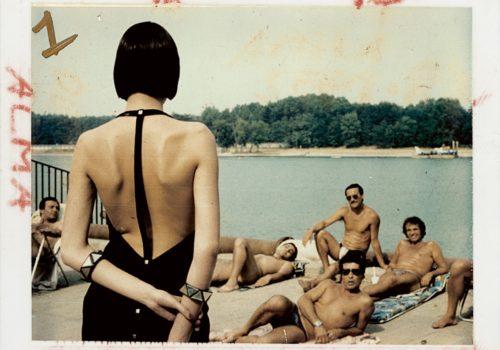

HN: Exactly. I did a series of photos for Oui. A series of photos that showed a woman walking naked under a fur coat in places as diverse as the subway, an art gallery, the Ile Saint-Louis , a car on the Champs-Elysees and a street in Paris. I know where these images come from: from a childhood fantasy. When I was 14-years-old, I read a novel by Arthur Schitzler called “Fraulein Else.” This is the story of a banker who just went bankrupt and has a beautiful 17-year-old daughter. A man offered to bail out her father if she agreed to walk down the hallway of a hotel naked under a fur coat. She hesitates but decides to do it. One night, she came down from her room and walked around the man opening her coat. The man didn’t touch her and saved her father. I love this novel, which was written in 1910 and is incredibly audacious for that period. This is where these images come from. With that said, the process of making this series was really dangerous. It’s forbidden to shoot in the subway without permission and I think for these types of photos, the RATP wouldn’t even have bothered replying. I also wanted to photograph on a riverboat. When I expressed this idea to the press manager of the company, he almost fainted, so I did everything secretly. We started the series in a sumptuous car, driven by a chauffer and parked at the corner between Rue de Berri and the Champs-Elysees on a Thursday at 1pm. The girl was naked and her only clothing was a veil. The onlookers were flabbergasted.

Photo: You love shocking people and there is a touch of vulgarity in your images.

HN: A touch? You are modest. My photos are marked with vulgarity. Creativity comes from bad taste and vulgarity. In 1957, when I worked in Europe for the first time for UK Vogue, the editor-in-chief gave me an extremely long list of things to avoid. There were no photos possible anymore. For another magazine, which I still collaborate with today, there are two editors who have the same state-of-mind. With incredible ingenuity, they keep looking for accessories such as scarves, chic handbags, ballet flats and flowing garments that hide the body and make me drunk with anger. They systematically choose all the things that a normal man would consider anti-sexual. Would I make love with a girl dressed in such a way? This is the first question I ask myself when I shoot fashion photos. These two editors don’t understand that. Their mothers were like that and they are perpetuating the tradition. Good taste is anti-fashion, anti-photo, anti-girl, anti-eroticism! Vulgarity is life, amusement, desire, extreme reactions!

Photo: Though you are extremely distant from the model in your voyeurism.

HN: Yes, voyeurism in photography is a necessary and professional sickness. Look at, capture, observe, frame, target. These are the laws of our field. The world is totally different when I look at it through the viewfinder. I always take a step back from what I see through my camera. I use it as a screen.

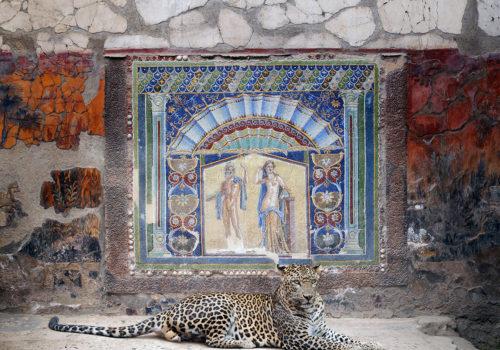

Photo: You often use swimming pools and hotel rooms as décor…

HN: Because I’m lazy. When I travel, I hate looking for outdoor places. I never go further than 2 or 3 km from the hotel. Plus, I love the hotels. This again,is a childhood fantasy. I love all the hotels, from the sumptuous old palaces, such as The Ritz, to the depressing, prison-like, cold, modern buildings. This is convenient, a hotel. There is room service and it’s less expensive than renting a studio. I even did two shoots in a brothel. The owner was reluctant, as he was not looking for publicity, but finally, he agreed. He loaned me a room on a slow day – Sunday, naturally. The second time, he saw me coming with the model, my assistant, the hairdresser and her assistant and he exclaimed, “Are you coming for an orgy or to take photos?!”

Photo: How do your images come to life?

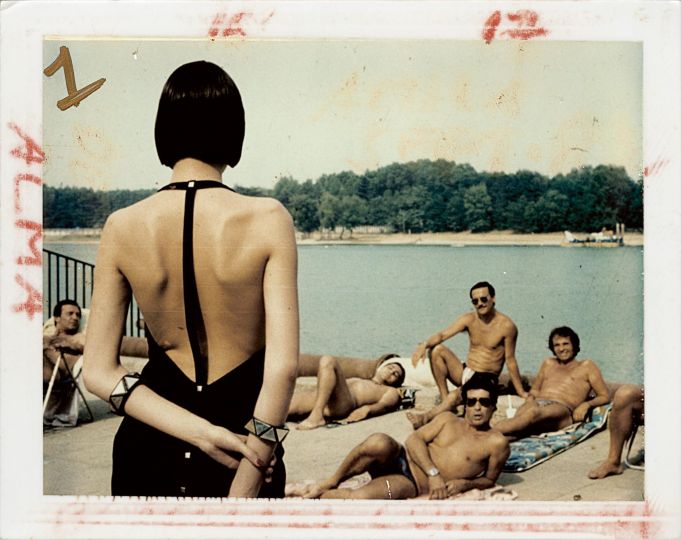

HN: They come from a student notebook. In it, I write down everything I’m interested in and it is divided into three sections: ideas, girls and locations. If I don’t write, I forget. All my notes are first in a standby mode, then they start on their way, ferment and finally take shape. Last year I saw on a beach in St. Tropez, two boys and a girl who were happy being together. A perfect harmonious trio. I reproduced this situation recently for a fashion series I did for Italian Vogue.

Photo: What was your childhood like?

HN: I was born more than forty years ago, in Berlin to a respectable, bourgeois family. I had a childhood without any problems and I adored my parents. When I turned 12, my father gave me my first camera. I did my first seven pictures in the subway. Naturally, we couldn’t see anything. The eighth image is from the radio tower in Berlin. My grades were deplorable. I was the biggest dunce of them all. When I turned 14, because at that time, school finished at 1pm, I got a job in the afternoon as a photographer’s assistant but didn’t tell my parents. This lasted for 6 months. My grades continued to get dramatically worse and my father took away my camera and locked me inside the house. At 16, my parents had lost all hope. I began as an apprentice for a portrait photographer named Yva, who was famous at the time. I’ve always wanted to be a photographer. When I was 13, I imagined I was in a raincoat, running around the world on the arm of a dreamlike creature and driving huge cars. At 14, I took photos of my friends in the streets wearing my mother’s dresses and hats. It’s during this time I promised myself that I would become a fashion photographer for Vogue. With Yva, I learned how to use a large-format camera, especially the 13×18. Yva had a really wonderful one with color slides. It was an enormous, heavy mahogany box that required a one-second exposure in the full sun at noon. At 18 years old, I left Germany to go to Australia.

Photo: Why?

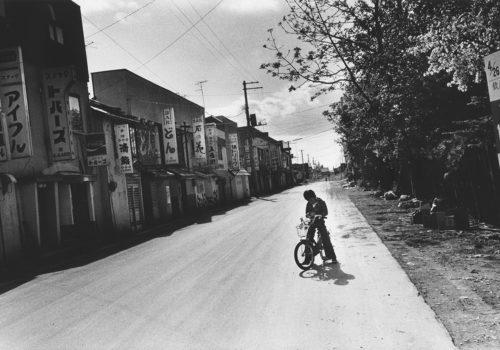

HN: Because I’m Jewish and, at that time, in Hitler’s Germany, this wasn’t entirely welcomed. One day in 1938, the Gestapo burst into my home and arrested my father. By chance, I wasn’t there. Warned by my mother, I hid for 2 weeks at a friend’s home in Berlin and then I ran away. I arrived in Italy and boarded a ship in Trieste, landed in Singapore, then finally left for Melbourne . I spent the 5 years of WWII in the Australian Army. If one day you are forced to fight, fight in the Australian Army. Everything is more relaxed, more humane than anywhere else. I started my military service as a chauffer for officers, then drove trucks, and at last as a photographer. When I shot my first cover for a magazine, The Australian Post, I ran around to all the newsstands to see it with tears in my eyes. It was impossible to survive being a fashion photographer in Australia, so to eat and survive, I did wedding photography. I hated that. The other photographers would open their competitor’s cameras to ruin the photos. It was at that time that I met June, who was a theatre actress. I was then shooting with a large 13×18 format camera with slides. The shutter was like a blind that you opened by pulling a string. Because of the retouching, it was necessary to use large-format. Even the 6×6 from the Rollei was considered too small. From 1954 to 1957, I went to London to work for Vogue UK. I’ve never been able to adapt. London is a city that I hate. It was not the swinging 60’s yet. My photos were terrible. One day, in 1958, I arrived in Paris with my portfolio under my arm. I went to see Jacques Moutin, the artistic director of Jardin des Modes, which was the best French fashion magazine at that time. Frank Horvat, Jeanloup Sieff, Marc Hispard and Jerome Ducrot collaborated to this magazine. Moutin met me and said: “If you settle in Paris, I will give you a job.” The dream! June and I, settled in the best room at Hotel Boissy d’Anglas. It cost 17 francs per night at that time. Moutin had only one fault: he never decided quickly who he would give an assignment to. He was always hesitating. June and I spent hours in front of Jardin des Modes at a patisserie on Rue Saint-Florentin with a coffee and half a croissant. I was continuously going back and forth. Anyway! It was wonderful. The day I arrived in Paris it was love at first sight. Within a week, I could travel throughout the city blindly. After a year, I had no money. I wasn’t working a lot. The fashion editorial pages were badly layed out and my photos weren’t good. I went back to Australia, where I got a wonderful contract that brought me enormous amounts of money. In 1961, I couldn’t wait any longer and June and I sold everything in Australia to move and settled in Paris. I started collaborating with French Vogue and then with Elle at which Roman Sieclewicz was the art director. My first attempt to collaborate with U.S. Vogue failed. The editor-in-chief, Diana Vreeland, had an extremely personal vision of what fashion photography should be. Women had to be exotic, baroque and unbelievable. The exact opposite of what I liked. I think women dressed by Diana Vreeland could not go out in the street without provoking an immediate protest. When she left Vogue, I started working for them again – better this time. I had a great connection with Alex Lieberman, the art director and head of Conde-Nast. He always chose, as far as I’m concerned, the best photos.

Photo: Technically, you are a jack-of-all-trades. There is no camera you haven’t tried.

HN: Yes, I’m searching, I’m trying, I’m experimenting, but this is a common practice. The range of amateur cameras is wider than professional. Why wouldn’t I be interested by it? The miniaturization of the bodies and the flashes can be really helpful. All my material today is composed of four bodies, five lenses, one flash, one Polaroid and everything fits in luggage that weighs 17 kilos, which allows me to take any type of photo, anywhere, in any condition.

Photo: How did you evolve technically?

HN: I started with a large-format Graflex, 4×5 inches, Super D, then I turned to Rolleiflex. I don’t like the Hasselblad, as it’s too heavy and too noisy. Afterwards, I consecutively used Nikon (in 1962, following the advice of Frank Horvat), Konica, Olympus and Instamatic. Today, my definitive choice is Nikon and Pentax. I recently got a Leica CL in my hands. This is a wonderful object, but I can’t use it. I don’t feel my images through this viewfinder. It took me a while to get used to the 24×36. From the Rolleiflex that you wear at your belly to the Nikon that you wear at eye-level, this is a very different vision and perspective.

Photo: Are you a fanatic of Kodachrome II?

HN: Yes, but this emulsion lacks sensitivity and it’s still too slow. I sometimes use Ektachrome X in certain conditions.

Photo: What are your favorite lenses?

HN: The longest possible one that still enables me to not lose the contact with the subject I’m shooting. When I shoot in a hotel or a studio, I always have my ass touching the wall. I don’t like the studio. I hate backgrounds and only feel at ease outside. I’m not a good technician. I was really bad. I’ve made some progress. The automatic system helped me a lot in that field. I built myself a technique based on simple means and, if possible, not requiring the help of an assistant. A large part of my work lies on the use of flash.

Photo: How do you evolve aesthetically?

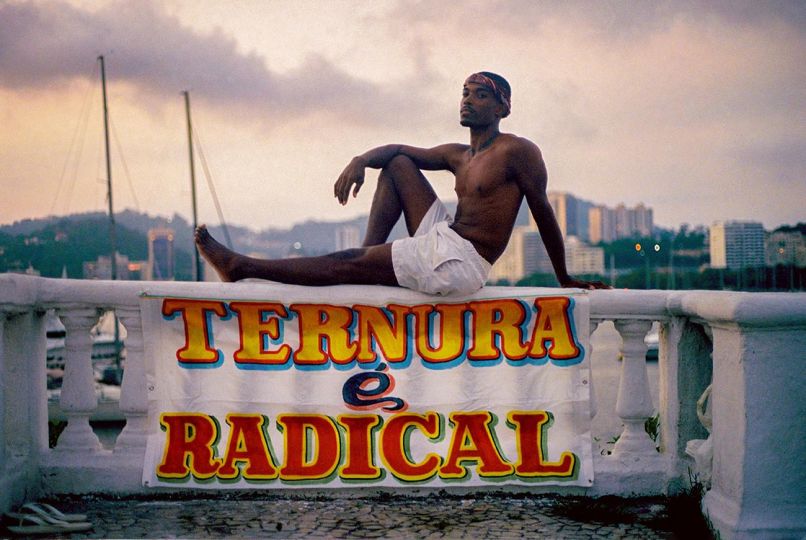

HN: Towards simplicity. I want to continue in the direction of my elite and erotic portraits. I am superficial. I’d rather photograph Regine and Catherine Deneuve instead of any scientist or writer. I love this superficial world. My images are not deep. I’m not an engaged photographer, nor am I a concerned or witness photographer. I’m not good at that. I love what we call the word and the half-word, the one that is artificial, beautiful and funny. The one of Regine and Castel. The one of fifty-year-old men dating 18-year-old chicks. I hope that this world will not disappear. Last week, a woman from WLM, who was not stupid at all, attacked me in a restaurant with rare violence yelling, “Sexist! Chauvinist!” I laughed like crazy. I had nothing to reply. I don’t care what she thinks and I will not change to please the WLM. I photograph the world I love. The world without money – I know it and I’m not interested in it. I’d rather photograph rich people than poor people. They are just funnier – maybe sometimes without being aware of it. Sometimes they are ridiculous, but often beautiful. It’s too easy to photograph poor people.

Photo: Which photographers have inspired you?

HN: Penn, Avedon, Baron de Meyer, Steichen, Honeighen Hune, William Klein, Weegee, Sander, Brassai and Lartigue.

Photo: We could say a few young photographers are shooting “some Newton.” What do you think about this?

HN: This amuses me enormously but I’m quite happy about it. In the beginning, one should always be inspired by someone you admire. I did the same thing when I was young. We always mimic someone at one point or another in our life, but then, we need to follow our own path.

Photo: What do you hate about photography?

HN: Dishonesty. The disgusting image shot in the name of an artistic principle. Blurry images. Grainy images. Bad technique.

Photo: To young boys who would love to become a photographer, what advice would you give them?

HN: Ideally, to be the assistant of the photographer of your choice, but not even 1 in 10,000 would get that opportunity. I think that a young photographer should be hired in a big, commercial studio in order to get familiarized and to learn the ABC’s of the technique. In the meantime, he should take photos whenever he has a free moment. When one wants to be a photographer, you should live exclusively towards achieving this goal.

Photo: What do you think about art directors?

HN: The splendor of their reign is over. Their influence is turned off. They have been replaced by the director of the magazine or by the commercial director. They don’t have decisional power anymore. The heyday of art direction is dead. What remains today? Alex Liberman at Vogue, Emile Laugier at Marie-Claire and Peter Knapp at Elle. I have never worked with Knapp, and during my first time at Elle, he didn’t think I was good enough. Today he wants some shots that are different from the ones I want to take.

Photo: Would you like to teach?

HN: Yes, this would captivate me. Jeanloup Sieff, Peter Knapp and I have imagined a project that we may achieve one day. This would consist of limited courses that would imitate real photo shoots. Maybe one day?