If I were to name the five most important people in my photography career, Edward Steichen would have to be on that list. I was only sixteen in 1947 when Steichen, then 68, became the Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. Three years later, in 1950, I walked into the museum unannounced asking to see him. I had previously received encouragement from Dorothy Norman to embrace my photographic career with gusto. Norman, a wealthy woman who was both artist and patron to the arts, as well as Stieglitz’s lover until he died, graciously told me: You’re young, but you will go far because you have awe. That is the password to wisdom. My visit to the museum as a young man of 19 was partly fueled by her encouragement. (For more on that see my blog: Thank you Dorothy Norman)

The man at the front desk called Steichen and I was invited up to his office to meet him. That day he purchased two of my photographs, which was pretty heady stuff for a 19 year old street photographer. (And still is even at 84). They were the first I had ever sold.

I was later to learn that Steichen himself found early encouragement in the same manner. When he was 21 years old, Steichen, who had never before met Alfred Stieglitz — then considered the taste maker in the photography world –stopped by to meet him in New York on his way to Paris to study painting. Stieglitz was impressed and purchased three of Steichen’s photographs for the sum of five dollars each. Steichen was elated, stating that he had never before sold one for more than 50¢! Shortly after arriving in Paris he abandoned painting and devoted himself to photography. I’m guessing that incident must have influenced Steichen to adopt the tradition of encouraging young and promising photographers by purchasing their work for MOMA’s collection. I was fortunate to be one of the recipients.

In the following decade he purchased several more photographs from me. But equally important to me was the level of access and moral support he provided. Whenever I dropped by he would greet me with, “Hey Feinstein, come on in!” when he saw me outside his office. It was definitely a different world!

Several years later, Steichen asked me to contribute a number of my photographs to the Family of Man Exhibition. I turned him down. Yes, it probably stands as the most foolish decision of my career. At the time I felt that the purpose of a museum was to show art. Period. Not because it fit into a specific theme; an opinion I totally renounce now. I was not the only photographer to decline his offer and I’m sure I’m not the only one to regret that. The exhibition is widely considered the most important one in the history of photography to date. And the book, which has sold over 4 million copies, is probably the most widely viewed photography book ever published. Not surprisingly, Steichen considered the exhibition his greatest creative achievement.

My regret is not only about the loss of visibility for my work. But, my purism at the time was really a contradiction to deeper strains of rebellion and populism within myself well expressed by my friend W. Eugene Smith when he said: “Hardening of the categories causes art disease.” Yet my own views at that time indicate that I was suffering from art disease myself! However, most importantly the theme of universal humanism, which the exhibition espoused could not be closer to my heart. If only I could turn back the clock!

In his exhibition commentary, Carl Sandburg wrote:

“The first cry of a baby in Chicago, or Zamboango, in Amsterdam or Rangoon, has the same pitch and key, each saying, “I am! I have come through! I belong! I am a member of the Family.”

In her book on Steichen, curator Barbara Haskell of The Whitney Museum, shares this perspective on Steichen’s influence at MOMA and on photography. It points to the fault-lines regarding the debate over thematic concepts vs.”pure art”. But she also lauds his encouragement of younger photographers.

“During Steichen’s fifteen-year tenure at MoMA, thematic concerns came to predominate. Aesthetic issues were marginalized as Steichen replaced one-artist shows with group presentations assembled on the basis of subject matter. Even in non-thematic surveys of contemporary photographers, he typically treated prints as conveyors of information rather than as precious objects by mounting them on thick boards without glass or mats and clustering them in graphically dramatic arrangements that resembled magazine layouts. Such orchestrations often overshadowed the work of individual photographers…..Steichen’s showmanship and populist bias were decried by photographers such as Ansel Adams, for whom Steichen was the ‘anti-Christ’ of photography and his regime a ‘body blow to the progress of creative photography.’ Still, Steichen served photography well, encouraging a host of younger artists by looking at their work, purchasing prints for the collection and including them in exhibitions. More important, his vision of photography as a democratic tool of mass communication attracted a wide popular following to the medium. Never did Steichen articulate his ambition for photography more forcefully than in his famous 1955 exhibition ‘The Family of Man,’ an immense, thematic presentation that he considered his highest accomplishment as a creative individual. To organize the extravaganza, Steichen spent more than three years culling two million photographic submissions. The 502 photographs he ultimately selected represented the work of 273 photographers from 68 counties.”

Not too long ago, Judith, in her attempt to organize my boxes of papers found in our basement, discovered this letter from the Photography Departmen at MOMA seeking more information on some of the photographs in the collection. Seeing Steichen’s signature somehow made him come alive again for me. The letter, dated April 15, 1960 would’ve been just a few days before my 29th birthday and I was teaching at the Philadelphia Museum School. It appears I filled it out, but never returned it. I recently contacted MOMA to see about getting my works listed in their on-line database and I was told to be patient. Only 10% of artists and works are currently represented on the website, and they’re chipping away at it slowly but surely. I completely understand and can only chuckle a bit when I consider how disorganized I was 55 years ago when I got this simple request! I will always remember Steichen as the most important early supporter of my work and I will always regret not partaking of the full feast he offered me!

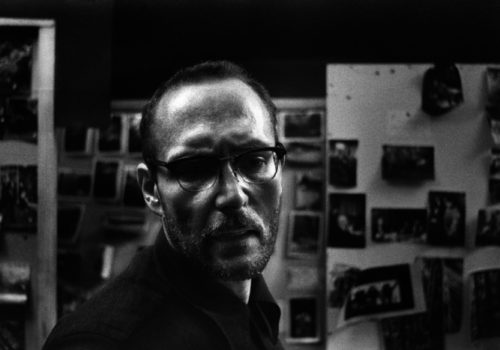

A postscript: For one of the photographs in the collections, portrait of W. Eugene Smith (1956), I notice that I added this remark: “Smith portrait made with considerable ferrocyanide control. In fact, the museum’s print is the only successful one to date!” Stay tuned for my up-coming posting about using ferrocyanide in the darkroom!