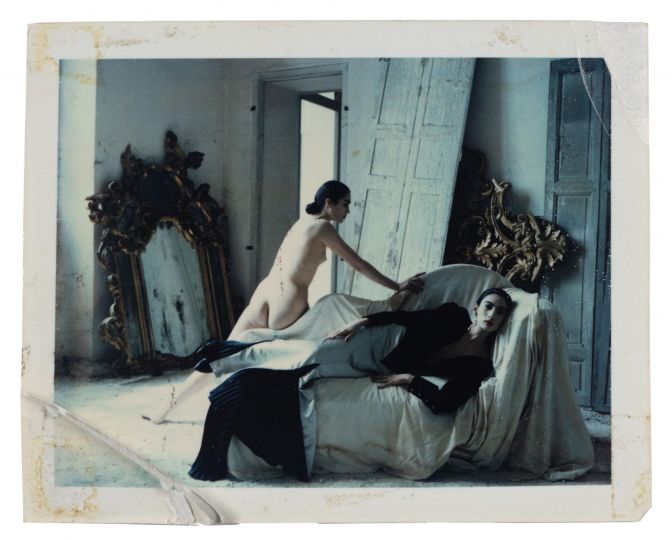

Guy Bourdin refused to publish books in his lifetime. For this extraordinary fashion photographer, printed images belonged in magazines, like Vogue, where he was a frequent contributor from 1955 to 1987, or in advertisements, like the ones he did for Charles Jourdan from 1967 to 1981, and nowhere else ,he refused books. Since Bourdin’s death on March 29, 1991, at the age of 62, his son, Samuel Bourdin, has attended to his father’s legacy. Three books have already been published: Exhibit A, a selection of 100 Bourdin photographs; the catalogue for the Guy Bourdin retrospective, which started out in London and traveled to Paris, Australia and China; and the most intimate of the releases, 67 Polaroids.

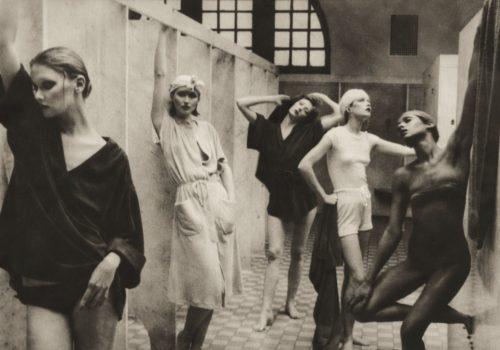

In 2006, Steidl published a two-volume reissue of A Letter for you. This is a book with feeling, part study and part memoir, a revealing look at one the greatest fashion photographers. Nicole Meyer, one of Bourdin’s favorite models, offers readers a glimpse of the man behind the legend.

Meyer was born in Los Angeles in 1959 to a French father and an American mother. When she was 12, her parents moved to Paris, where Nicolle lived a tranquil life studying dance until the fateful day she met Guy Bourdin. For three intense years, from 1977 to 1980, she worked almost exclusively for Bourdin, shooting indoors and outdoors for ad campaigns, magazine spreads and even a calendar for Pentax. She had a front-row seat on the evolution of his singular body of work. This interview was conducted in Toulouse in February 2006 and published the same year in french Vogue .

How did you meet Guy Bourdin?

I was a ballet dancer at the time. When I was 16, I saw an ad at the Salle Pleyel, where I was taking classes, seeking models for a fashion show in Japan. I spent a few weeks over there, and when I got back to Paris I joined a modeling agency (that went bankrupt soon after). One day, they sent me to Guy Bourdin’s. The bookers thought it would work because I had a round face and curly hair. I showed up at his studio on the Rue des Ecouffes, in the Marais. He received me immediately, very nice, soft-spoken, gentle. I had no idea who he was. The fashion world was very foreign to me. He spent a few minutes looking at the three lousy photos I was using for my lookbook, then he asked to see my ID. The next week he called me for a series in Vogue, and that was it!

Do you remember your first session?

It was for raincoats. I left the shoot dripping wet. My head was cut off in the first pictures. I felt like he was testing my resistance.

What kind of models did he like?

The natural kind, all-American, wholesome, with round cheeks, and not too tall, I was 1.75m (5’9”). He liked to use amateurs and the people around him, like his friends and assistants. I also worked with Alexis, the older sister of Debbie and Janice Dickinson. She was a journalist, not a model.

Legend has it that he could be severe with his models.

That’s no legend. But he wasn’t that way with me, maybe because I came from the dance world and I had a different work ethic. He never asked he to do difficult poses because you had to hold them for so long. He was very polite, paternal. Most of the time I was the only model, but there were others, too. He liked to see sparks fly between models, but I’m pretty easy to get along with.

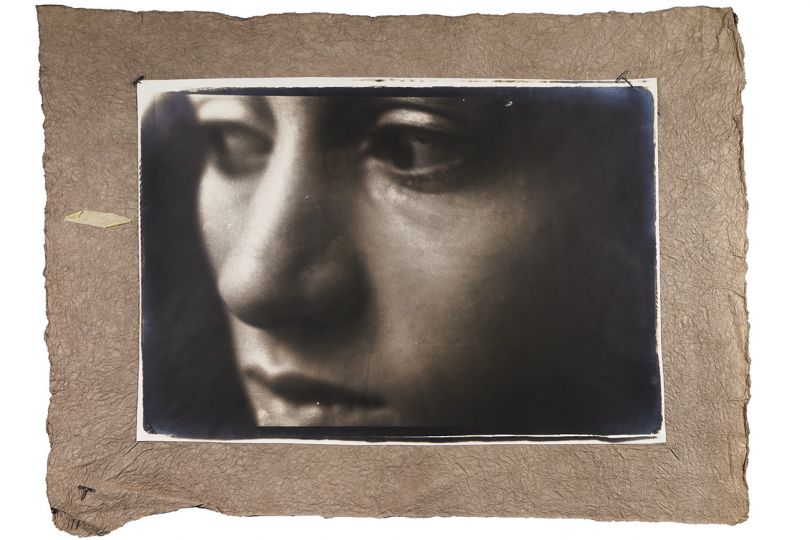

How important was the makeup?

The makeup was typical: well-defined cheekbones, dark circles around the eyes with lots of mascara, fake eyelashes, a bright red mouth. For every photo he spent a long time working with his makeup artist, Heidi Morawetz.

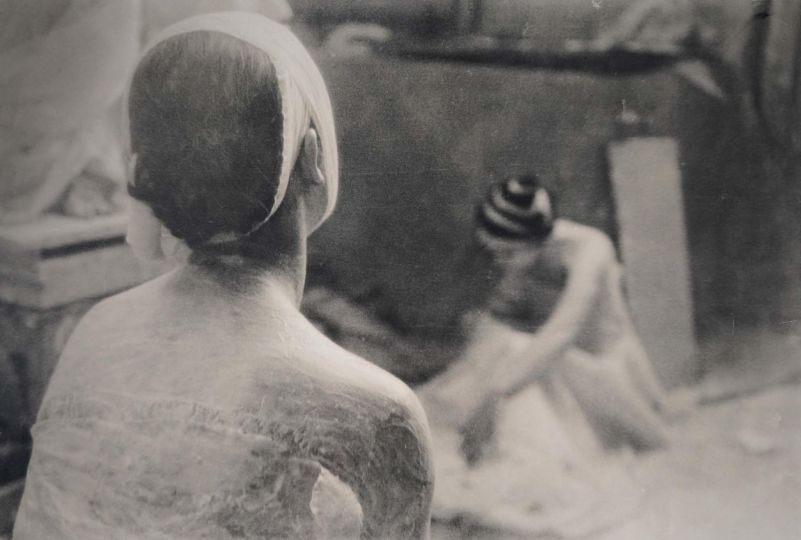

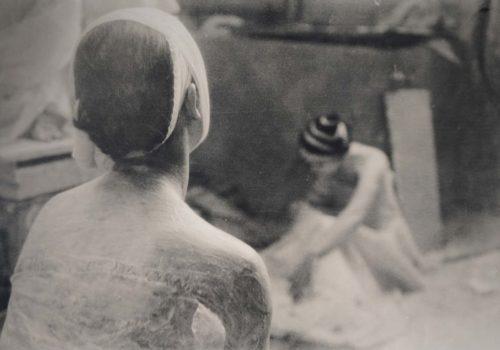

What were the photo shoots like?

He started with a very clear idea. He always had notebooks with him where he’d jot down ideas, and he always sketched it out first. He worked very closely with his assistant, Icaro. Sometimes he would have large sets built, like an enormous shoebox. Most of the time it was Icaro who built the sets, and sometimes there were others to give him a hand.

The atmosphere was special. It felt like a family. There was no rush. You could spend the whole day shooting a single photo. You couldn’t do that today. And Valentin was there, his hairstylist. There were always friends passing through, always wine and saucisson. It wasn’t so tightly organized as it is now, everything was informal. When we went to his house in La Chapelle-sur-Dun in Haute Normandie, we were like a family. We all slept in this little house. I’ll never forget that he had a friend who would make fried flowers. You’d eat them with sugar!

Were there drugs?

Very few, considering the time period. A few joints every now and then. But it was mostly wine!

Was there a stylist?

For Jourdan, Heidi was the makeup artist and the stylist. For Vogue he worked a lot with Patrick Hourcade.

Did you listen to music?

All the time: Devo, Earth Wind & Fire, Ian Dury, Grace Jones, Blondie. I was always dancing.

You also worked with other photographers.

Yes, with Paolo Roversi, Peter Lindberg and Toscani. I was in high demand once I stopped.

Never Helmut Newton?

No, I didn’t have that Amazonian look he was after. And I had small breasts. Maybe there were models who worked for Newton and Bourdin, I’m not sure.

How has modeling changed today?

We already did “go-sees” back then, but you could say that it was more artisanal. My book only had Guy Bourdin shots in it. The photographers didn’t care but the editors did. For them my style was too recognizably Bourdin’s, with this stark, unnatural makeup. They couldn’t see me otherwise.

What was your relationship like outside of modeling?

It was strictly professional. There was a huge age difference between us. I was 17 when I started and he was 49!

Do you think he liked fashion?

I think so, yes. But I don’t think he followed fashion shows. He loved what Karl Lagerfeld was doing, but Guy was so deep in his own world. He wasn’t that into the whole machinery of fashion, but when he thought a garment didn’t fit with his idea for the picture, he’d let it be known immediately. He was a real aesthete. I don’t think he respected fashion in his photos, even though they were fashion photos. Fashion was secondary.

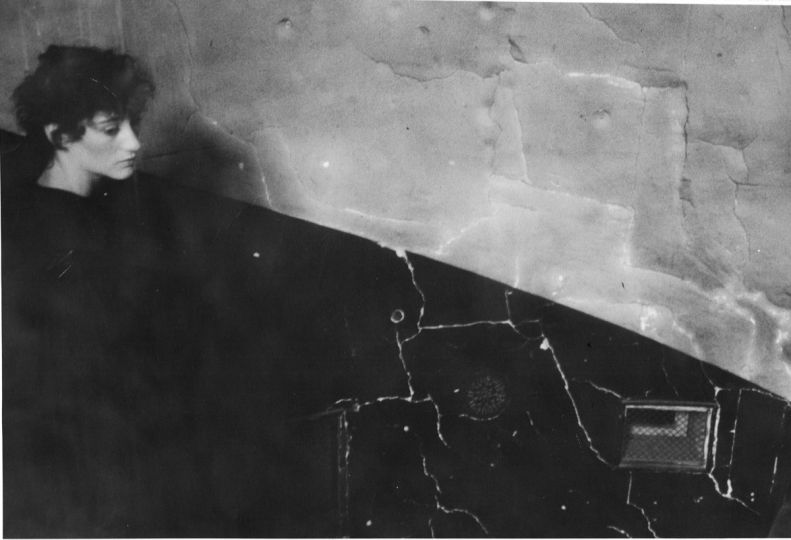

How did he live?

He made a good living doing ad campaigns, but he lived modestly. Later, when he made the cover for our last album, Out of Blue, he invited me to his house on Rue de Pélican near the Louvre, and it was very modest: a fifth-floor walkup, an attic duplex with a central staircase. He had a studio there, and he was still working on one or two paintings.

You spent two months in the United States from December 1977 to January 1978 for a long photo shoot.

There was so much to shoot: a campaign for Jourdan, Vogue, Bloomingdale’s (not the famous catalogue, that was with Rita and the Dickinson sisters), Calvin Klein. It was basically a road trip across the United States. When we landed in Houston, Guy bought a black Cadillac—in my name—and a van, and then we took off with Heidi, Valentin, his wife Katia, who was also a stylist and hairdresser, and a young assistant. We stayed at the Fontainebleau hotel in Florida and spent a month roaming Miami, which looked nothing like it does today. Another model, Maxi, was with us in Miami. While we were doing makeup at the hotel, Guy would scout locations. One day in Miami, he found a shop window with mannequins in it, and he came back to get me and made me pose with them. He would take polaroids, or films that he would have developed the same day for the location scouting. But sometimes we just hung out. He would look out at the landscape. He wanted to travel and nothing else. He bought some cowboy boots, we went to restaurants. He was freaking out because there was so much work to do and it kept raining. Guy got so angry. It was really dramatic.

How did this book come about?

Initially, Samuel, Guy’s son, contacted me asking for permission to use a picture of me on the cover of Exhibit A, the first book he did. He knew that I was living around Bastille, but I had already left for Mexico. He found me through my brother, who has a gallery in Saint Germain des Près.

Then there was a retrospective at V&A in London, organized by Shelly Verthime. She started asking me questions about dates and certain photo shoots, and we became friends. We quickly saw that there was more to be explored in Guy’s work, and we found a lot of unpublished material: polaroids, writings, poems, drawings.

How much of Guy Bourdin’s work do we know?

There is an enormous amount of photographs, many of which have never been seen. It will take a lot of time to go through the archives in New York and Paris. Once I opened a box labeled simply ‘Knoll’ (the brand) and there was a whole series with a nude woman on color pillows. It was superb. And I was the only person who had seen it. I don’t remember that session in particular. He was prolific, always full of ideas. He had a carte blanche with Vogue and Charles Jourdan, but there were a lot of photographs rejected by other clients.

It turns out that he was a great lover of poetry, which he also wrote. He was constantly writing and reading. He had a very romantic and literary side. His favorite authors were Balzac and Edgar Allan Poe. He was very cultivated. Wherever we traveled we went to museums. You can see the references to art history in his photographs, like in his tribute to Saint Sebastian where I’m hanging from a cross in the garden of Karl Lagerfeld’s chateau, and my breasts are dripping blood.

Patrick Remy

Book

A Message for You

Guy Bourdin

Curated & written by Nicolle Meyer

Ed Steidl.

48€