Ashton Kutcher, Kevin Costner, Matt Dillon, Rupert Everett, Charlie Sexton, Leonardo Di Caprio, Marc Wahlberg, Josh Hartnett and Viggo Mortensen. All of them between 18 and 25 years old. They are young, they are beautiful and they are all on the verge of becoming very famous. The photographs are taken by Greg Gorman and they are all collected in the book “In their Youth” published by Damiani.

AN INTERVIEW WITH GREG GORMAN

The following interview was recorded in Greg Gorman’s studio in Mendocino, California, on a windy night in December 2008. Audrey Wells, friend and filmmaker, asked the questions over a bottle of Toulouse Pinot Noir 2005.

Wells: You did the layout for this book yourself. How many photos did you start with?

Gorman: We scanned over a thousand pictures, which were culled from 35 years of archives. Bringing that number down to about two hundred became an exercise in determining which images best represented the range of feeling and expression that I was after.

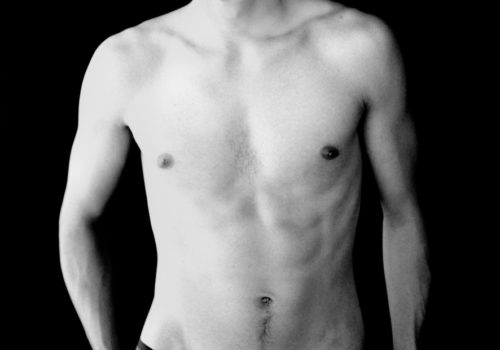

Wells: The photographs in this book elevate male beauty to something almost mythic, and yet they are intensely human as well. The pictures have emotional mystery; I felt as if every portrait was revealing a secret.

Gorman: The thing I realized working on this project, was the fact that if I end up being remembered for anything, it will be for my up front, close in portraiture. Throughout my career I have found that I have achieved my most telling, significant pictures when I got in close with a long lens. That’s how I cut through all the barriers, all the boundaries, got into my subject’s head and understood them better. As soon as you start to pull the camera back, you lose focus in terms of who that person really is. That’s why you won’t see a lot of backgrounds in these pictures; they are really about the person, not the elements. They boil down to the graphics of the individual.

Wells: “The graphics of the individual.” What do you mean by that exactly?

Gorman: Body gesture, tone, angle, shape, form and balance; what is being revealed in the highlights, and what’s being kept from you as a secret in the shadows. I don’t think my photography is about answering all the questions. It’s about leaving a little bit to the imagination. When there’s a dark side to a picture, it makes you wish that you knew a little bit more, and it draws you in.

Wells: You’ve always said that a good photograph exists in the eyes.

Gorman: The eyes tell you if you’re getting through to the heart of the individual, or if there’s something they’re not sharing with you. After spending so many years of my life behind a lens, I can clock a person pretty quickly, and give you an honest assessment as to where they are. The challenge I’ve faced in the course of forty years of taking portraits is in breaking through the barriers and the facades that people sometimes try to put up.

Wells: How do you do that?

Gorman: I think you have to share your vision about what you’re doing, and you have to make them trust you. If the trust isn’t there, the pictures don’t really come.

Wells: But trust is something that can only be earned over a long period of time and through shared experience. So often these people coming to you only know you ten minutes before you take their picture. So how do you get them to trust you?

Gorman: By being a sort of psychologist, I guess. You have to figure out in a very short amount of time where they’re coming from. Sometimes you guess it right, sometimes not. You must be able to come up or down to their level to win their trust and confidence. I was always interested in the pictures that my subject and I would both be proud of at the end of the day.

Wells: There are many photographs of famous actors in your book, shot when they were still teenagers or in their early twenties. They are stunningly candid.

Gorman: A lot of the pictures that I created in the early days would be virtually impossible to create today. The publicists today would never allow their actors to do these kinds of pictures. Not that these are necessarily objectionable images — but they would probably feel they weren’t helpful in terms of pushing their clients’ careers at this stage. My celebrity photographs were never intended to position careers. I was just going for a great photograph. Leonardo, from the first day we shot, was really into photography. He was as focused in front of my lens as he was in front of any cinematographer’s camera. He looked at taking stills like playing a part in a movie. I think that’s why his pictures are so powerful, and he looks so amazing. We did so many shoots, back in his late teens, early twenties.

Wells: He looked very free with you.

Gorman: Very comfortable. He was never worried about projecting the wrong sexuality or appearing too vulnerable. He was interested in creating a picture. It was just the two of us. I’m fortunate to have long-term relationships with a lot of people who still want to go out and play. But it’s very different than it used to be.

Wells: In your layout of this book, you juxtaposed photographs of world famous celebrities with pictures of unknowns. Some of these “regular” people are living, some are dead. I think there are some whose names you don’t even know anymore. Why did you decide to arrange the book this way?

Gorman: I think that’s one of my favorite things about the book: the element of the unknown. I wanted to make people wonder about who they were looking at. Are you appreciating the picture only because it’s a famous person? Or can you appreciate the picture because of the sheer beauty of the individual? In my eyes, everybody is interesting; a celebrity, so to speak, in their own right. When I’m inspired to photograph somebody, it doesn’t matter to me what their profession is. The beauty, the essence of the person’s being, is still there, whether he’s famous or not. This is something I always found fascinating with Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine in the eighties. You could look through the magazine and see Tom Cruise on one page, and next to him you’d see some kid that Andy met at Studio 54 the night before, whom he found fascinating for one reason or another; almost like a muse. But in the power of their photographic images, they were equals. Many so-called “unknowns” have served as muses for me.

Wells: And have there been famous muses as well?

Gorman: Leonardo, certainly. Every time we’d shoot we’d have a different scenario and create a different body of work. That made him consistently interesting to photograph over a period of time. More recently, I’ve been photographing a young actor named Alex Pettyfer. We have a photographic relationship that’s spontaneous and connected, in which we provoke, push and disturb each other into creating strong images. We play off each other in a symbiotic relationship that allows great work to develop. And that’s why I call Alex a muse of mine, and why I wanted to close the book on those pictures, which showcase some of my most recent work.

Wells: The title of your book, In Their Youth, implies, inherently, that youth ends, something is lost, and then you start another time in your life. When does it happen that you can’t shoot someone “in their youth” any more? When does that day come?

Gorman: That’s a tough question to answer. I think some people always stay in their youth and are always in that moment. I feel I have included some of these in this project -such as David Bowie and Mick Jagger. But I think that for a lot of people, they do move on. Their adult awareness becomes stronger and the concept of responsibility takes over. They begin to lose the particular beauty and naiveté that you see in these portraits. There’s a certain innocence, an unjaded honesty that you see in the eyes, that diminishes as men gain age, experience and knowledge. It’s a natural progression that happens. But it’s something that does change and alter the way my subjects look into the lens.

Wells: Some of the photographs in this book were taken about thirty-five years ago. It occurs to me that you were also “in your youth” back then. How do you think you’ve changed as an artist, as you’ve left your own youth behind?

Gorman: I have certainly changed, in terms of how I look at life. I would definitely say that I have become more cynical, more aware of a lot of things. After thirty-five years of taking pictures like this, my subjective influence and life experience would probably cause me to capture these people in a different light. So I’m glad that I approached them the way I did at the time – More freely and with less judgment.

Wells: You seem to be saying that your early work was more innocent and open, like your subjects; but that as you matured, it lost some of those qualities.

Gorman: Ironically, yes. I think so. In the second half of my career shooting film, I was more guarded, more staid, less relaxed in terms of how I worked. But now that I’m part of the digital age, I’ve become more playful again. Once I know I have the capture that’s the needed photograph, I’ll let the shoot play out, let my subjects experiment more in front of the camera, which brings me closer to what I was achieving in the earlier days. Digital has brought back a lot of spontaneity in my work.

Wells: When I look at these photographs, I can feel the sexual and sensual energy coming off the page. It makes me think about the person on the other side of the lens, holding the camera. You have an incredible connection with your subjects. How do you get to that place so consistently?

Gorman: I’m usually attracted to the people I’m photographing, whether they are male or female. I think that’s the only way you’re really going to get a great picture; you can be physically attracted to a person or mentally attracted to a person, but one of those two elements needs to come into play to get a succinct portrait. If there’s not a connection on one of those two levels, it’s difficult to get the communication channels open and flowing. I would say that my attraction to the majority of the people in the book certainly didn’t hurt the process of how I pulled everything out of them and captured the pictures; but everything begins with a foundation of trust, understanding and confidence. You can’t get a connected portrait without those things.

Wells: I think for an American male to make a book about male beauty, young male beauty, and to celebrate it in its full spectrum, is still to do something taboo in this culture.

Gorman: Oh, I agree with you. And, you know, I’ve done seven books, and I made my career and my life shooting celebrities. It was a good living and I had a great time and I enjoyed it and I met so many amazing people. But I also know who I am and what my interests are and where my heart falls. I wanted to do a book that was about that; about my vision, about what has driven me to photograph for forty years, outside of the commercial work that I did. I wanted to share something that was a part of me.

END

THE MOMENT OF BEAUTY

By Peter Weiermair

“Wer die Schönheit angeschaut mit Augen ist dem Tode schon anheimgegeben” August, Graf von Platen*

This volume culled from over one thousand edited images from the archives of Greg Gorman was selected by himself in the form of a” bequest during his lifetime”. It is without doubt, the most personal evidence of his obsessive search for pictures of radiant manly youth and his concept of beauty, which can only be realized in the form of a black-and-white print as seen in the photograph. This notion of a contemporary version of “mens sana in corpore sano” from this neo-Roman or neo-Greek artist almost persuaded me to set an antique Antinous, the short-lived lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, at the head of these reflections. The selection represents above all a celebration of the face, the classical form of the portrait, which photography took over from painting. Beyond that, Gorman supplements his selection of heads with figure studies, with their varieties of body language, where the erotic imagination of both model and photographer becomes manifest. The over two hundred works reproduced here were imposed by Gorman on a graphic grid, where both the dialogue between different subjects as well as the confrontation of a figure and a portrait of the same subject are significant. Greg Gorman excludes the environment, and gains timelessness by doing so. Body language, the play of the eyes, facial expression and the position of the head become important. In most cases we get to know the young man – for these are not really youths but young men – only through one picture and most remain anonymous although they have names. Only in a few cases does the public image of the person awaken in our memories, in which case Gorman corrects it. The book displays a long stretch of images at the beginning and again at the end – at the beginning di Caprio is seen in seven photos, where he is seen in his youth, in the early nineties and at the end, also with seven photos of Alex Pettyfer, taken this year, provoking a series of images that document Gorman’s continual search for eternal youth. Let us not forget that Gorman is accustomed to working with actors, who practice slipping into roles and playing roles, and his idea is to show them metaphorically “naked”, in other words without a role, with a still fragile identity not fixed in their youth and with an openess and accessibility which is essential to the fascination of the adult world in their still unconscious beauty and vitality. In this early phase of openness, an androgynous state, an almost feminine side, which is clear in many pictures, becomes visible. Photography is the legitimate means to document a fleeting, temporary condition of youth rather than the painful time of puberty (not caterpillar but butterfly). “There’s a beauty in some of the naiveté that you see in the portraits. There is a certain innocence, an unjaded honesty, that you see in the eyes, that I feel does get lost as men gain age, experience and knowledge” (Greg Gorman). Let us not forget! The realisation of a portrait is, for the photographer as well as for the subject, an act of dialogue between the two. The photographer, distanced from the subject whose image he desires, becomes a voyeur, the subject, in an extreme case, a narcissistic exhibitionist. Peter Hujar once expressed the opinion to me that the photographer is like a doctor, in front of whom the patient (model) disrobes. Greg Gorman speaks of trust as a necessary condition of dialogue. He is fascinated by the relationship of individuals to each other, for example in the case of two similar friends like the self-presenters Luigi and Luca. In his book “Just Between Us” he moved into personal spaces, becoming an observer of both psychological and physical self-statements of his subject. If photography is a document of a previous dialogue between the subject and the photographer, the photograph itself, for us who have to go without the physical presence of the person, is the actual experience of the image. The French philosopher Roland Barthes has spoken of the “punctum”, the moment in front of an unknown photograph where we start our interpretation, where our fascination begins and where we are able to narrate our story with the picture. It is “our” task, according to Gorman, to cast light into the dark aspects of the photograph. In the past, the photographic representation of the face was called a “mirror of the soul”; however, since the debates of the seventies in the last century on the capacity of photography to be true and to reproduce reality with the occurrence of scepticism, the authenticity of the portrait is of less interest to us. What are these pictures but documents of Greg Gorman’s still unending search for beauty, youth and sensuality.

Peter Weiermair

*Anyone who looks beauty in the eye is already at the mercy of death August, Graf von Platen

Peter Weiermair (born 1944) was the head of museums in Austria, Germany and Italy from1968 to 2005. He is a specialist in the field of modern and contemporary drawings and photography and lives as a publisher, curator and writer in Innsbruck, Frankfurt, Bangkok and New York City.