The Battle for History – Texte par Chris Klatell

The first copies of Whatever You Say, Say Nothing and the Annals of the North left Steidl almost 100 years to the day after the partition of Ireland on May 3, 1921.

Had the books been published earlier, closer to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and before Brexit and the reawakening of nationalism across Europe, they might have been received as valedictory: A reminder of the bad old days that pre-dated the peace process. But today everyone involved realizes the war’s not over.

The war doesn’t necessarily mean military or paramilitary conflict, although Loyalist communities continue to arm themselves and to seethe with rage at the post-Brexit border emerging in the Irish Sea. Nor does it mean only electoral politics, even as demographics and economics push politically towards the seeming inevitability of a reunited Ireland. The primary front in the war, at the moment, is the battle for history.

As Gilles and I have argued elsewhere, for millennia history was written by the victors: You won the war, massacred your enemies, and then controlled the story of their destruction. But we’ve moved into a narrative epoch in which history is no longer written by a conflict’s victors. Today, the victors are often determined, ex post, by whoever authors the conflict’s history.

This battle continues to play out across the North of Ireland, most desperately for the British, whose last remaining interest in the conflict is to absolve themselves of blame. Ireland was Britain’s first colony, and the North may be its last. History’s verdict on Ireland stands as a judgment on the entire British imperial experiment, and on Britain itself.

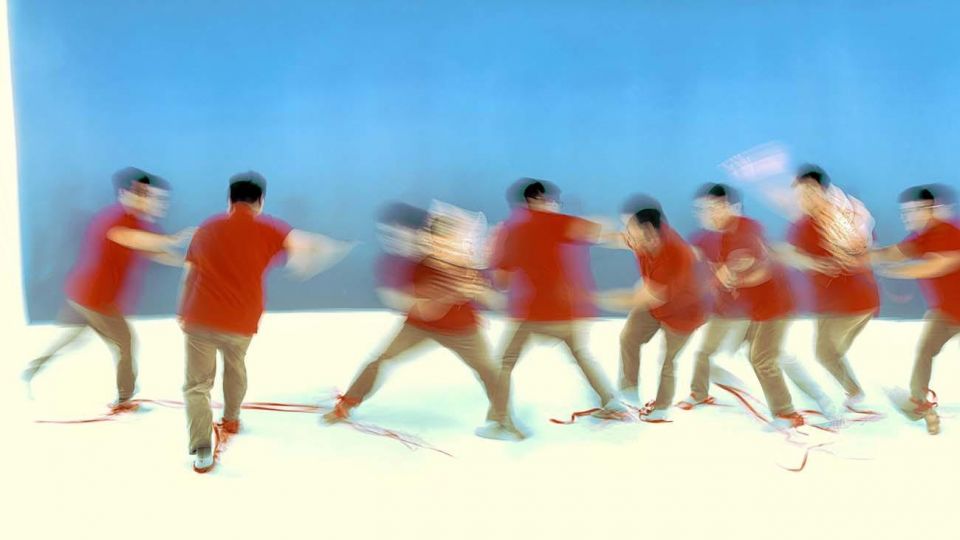

The battle for history became apparent as Gilles continued to photograph in the North from the 1990s onwards, switching to color to find a language that matched the new structure of time in the peace-process era. Looking at these images, I asked him about the prevalence of dusk, so distinct from the light in Whatever You Say, Say Nothing. While answering in French, he used an expression I’d never heard before: l’heure entre chien et loup; the hour when you can’t discern if the figure on the horizon is a dog or a wolf. We both knew immediately it was the perfect phrase to encapsulate this moment in the North – perhaps in the world – and the title of the book about this period that will one day be written.

–Chris Klatell