Richard Avedon once referred to George Hoyningen-Huene as “The master of us all”. Well, the master has gained increased visibility in recent years, since Tommy Rönngren, co-founder of Fotografiska, and his wife Åsa Rönngren acquired the George Hoyningen-Huene Estate Archives in 2020 from Richard J. Horst, the adopted son and heir to photographer Horst P. Horst. In addition to exhibitions, there is a monograph scheduled for publication early 2024, as well as a drama series. Tommy Rönngren explains.

I have always been attracted by great stories. Hoyningen-Huene was not only a fantastic photographer, the story of his life is incredible. He grew up in Tsarist Russia, fled the Bolsheviks in 1917, and ended up in Paris where he established a successful career, first as an illustrator, then as a photographer. He was friends with Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, Christian Bérard, Pavel Tchelitchew to name just a few, and was at the very heart of the Paris scene in the late 1920s and ’30s. Later on, he worked as a teacher at the Art School Center of Los Angeles and launched a second career, as colour coordinator for George Cukor in Hollywood. He was a very complex person and the ins and outs of his life never fail to surprise me.

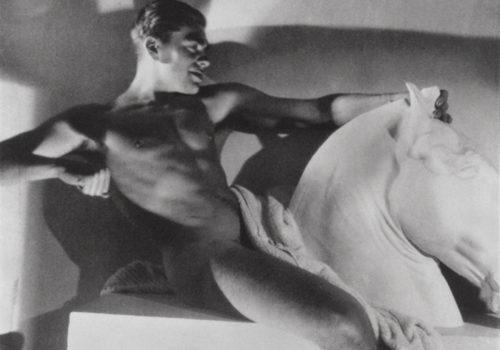

Rönngren and his team continue to make discoveries. Looking at Hoyningen-Huene’s fashion images and portraits for Vogue and Vanity Fair, I’m struck not only by their elegance but also how effortless they seem. But achieving that quality was anything but effortless, as William A. Ewing noted in his book The Photographic Art of Hoyningen-Huene (1986). In the first part of his career, Hoyningen-Huene worked mainly in studios. He used intricate lighting, often creating complex chiaroscuro effects and as light meters hadn’t been invented yet, this required meticulous planning. In addition, films suitable for indoor use were slow, so any movement would create a blur. The images of models, seemingly moving across the floor, with dresses or shawls billowing out behind them, were achieved by having them lying in static poses on the floor, with fabric and dresses arranged to simulate movement. Swimwear by Izod (1930) is another example of his ingenuity. It appears to show a couple sitting on a diving board looking out to the sea, but the image was taken on the roof of the Vogue studio in Paris, the board consisting of two boxes, with the slightly out of focus parapet creating an illusion of the horizon.

Hoyningen-Huene had an innate sense of style. He was born in St Petersburg on 4 September 1900, the son of Baron Barthold von Hoyningen-Huene, a Baltic nobleman, and his wife, Anne Van Ness Lothrop, originally from Grosse Point, Michigan. Baron Foelkersam, a close family friend and curator at the Hermitage, provided his first education in art history, taking him on lengthy tours of the museum. He became more and more fascinated by the classical world and the ideals of Ancient Greek sculpture would later inform much of his photography.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, the Baron sent his wife and son to Yalta to be out of harm’s way, while the two daughters enrolled as nurses. Following the October revolution in 1917, mother and son fled via Finland, Sweden and Norway to England. In 1919, at the age of nineteen, he enlisted in the British Expeditionary Force, part of the allied intervention in the Russian civil war, to support the White Russians against the Bolsheviks. It took some time before his unit engaged in active combat, but when it did, it was at the Battle of Tsaritsyn, later to be called “the Red Verdun”. Among the Bolshevik high command was none other than Josef Stalin. In January 1920, the Bolsheviks gained the upper hand. During the chaotic evacuation of the White Russians, Hoyningen-Huene, like so many others, caught typhus and nearly died, but was finally able to reach safety in England. As for Tsaritsyn, it was renamed Stalingrad in 1925, then Volgograd in 1961.

Hoyningen-Huene left England and settled in Paris, taking a series of odd jobs, including work as a translator and a film extra. His sister Betty, who had settled in Paris in 1917, had a successful dressmaking business, Yteb, and suggested that he, a talented draughtsman, make illustrations to promote it. To hone his skills, he took lessons from Cubist painter André Lhote and within a couple of years, he was selling his work to Harper’s Bazaar and Le Jardin des Modes. In 1925, he signed a contract with French Vogue as an illustrator, and to assist in its newly opened photographic studio, work which included designing backdrops. His baptism as a photographer occurred in 1926, when the photographer who was scheduled for the day’s shoot failed to appear. The fashion editor, Main Bocher, who established the couture house of Mainbocher in 1929, told him to get on with it and do it himself.

Hoyningen-Huene’s entry into photography coincided with a shift in the art world. Picasso had embraced Classicism in 1914, followed in 1919 by Giorgio de Chirico. In 1926, Jean Cocteau published Le rappel à l’ordre, a book of essays which gave name to the so-called Return to Order movement, rejecting the trappings of the avant-garde movements in favour of more traditional approaches to making art.

In his photography, Hoyningen-Huene would often use classical columns, vases and sculpture but it was not a case of simply raiding Ancient Greece for props. Far more important was his profound understanding of classical sculpture, combining naturalism, idealisation, and balance in the models’ poses, as well as conveying a sense of inner calm. This, combined with the technical challenges, was time consuming work. In order not to tire the models, he would use stand-ins until everything was arranged to perfection. Sometimes he would make enlargements of his own photographs to use as backdrops, the first photographer to do so, a method later employed by Erwin Blumenfeld and Cecil Beaton among others.

In 1930, he met Horst P. Bohrmann, who later changed his name Horst P. Horst. The young German had come to Paris to study architecture under Le Corbusier but was soon assisting Hoyningen-Huene in the Vogue studio. In 1931, Horst took his first photographs for the magazine. The two had adjoining apartments and within a few years, a holiday home in Hammamet in Tunisia. Hoyningen-Huene travelled extensively on assignment during those years, destinations including Berlin, New York and Hollywood. While some, among them Lisa Fonssagrives, found it a pleasure to work with him, he would strike terror in others. He became increasingly temperamental and volatile, often storming out of sessions. He was a constant worry for Condé Nast, publisher of Vogue. And then in 1935, he left for the rival publication Harper’s Bazaar.

The story of Hoyningen-Huene’s defection has passed into legend. By 1935, Dr M. F. Agha, art director at Vogue, had had enough of him. Agha flew from New York to Paris, set up a meeting in a restaurant, and told the troublesome photographer that his contract would only be renewed, if he “promised to behave”. Hoyningen-Huene was outraged at being scolded, like a schoolboy, by a “Ukrainian-Turk”. He knocked over the table they were sitting at and stormed out. And according to the legend, Hoyningen-Huene immediately went to the nearest telephone booth, called Carmel Snow, editor at Harper’s Bazaar, who was in Paris for the new collections, and told her, “I’m on the street and you can have me!”. In Snow’s telling of the story, Agha was still wiping sauce béarnaise off his lap when Hoyningen-Huene returned to the restaurant, triumphantly informing him that Snow had hired him on the spot. It’s a good story, but it has a few holes, as Penelope Rowlands noted in her biography of Snow, A Dash of Daring (2008). It did in fact take Hoyningen-Huene a few agonising days to decide to make the leap to Harper’s Bazaar. But he did stop photographing the collections for Vogue midstream, and at Agha’s suggestion, Horst immediately took over the assignment.

Hoyningen-Huene would remain at Harper’s Bazaar until 1946. But fashion was changing, and with it, fashion photography. In an unpublished interview, conducted in July 1994 and preserved in the archives of MoMA, Richard Avedon told Calvin Tomlins, about meeting Hoyningen-Huene in 1946 as he stepped into the elevator at the Harper’s Bazaar studio on the corner of Madison Avenue and East 58th Street, and was asked, “Are you the new photographer working on the Bazaar?” Avedon smiled and nodded, “Too late, too late”, Hoyningen-Huene said, indicating that fashion photography was over. Well, it was for him and his particular sense of style and elegance. For the 22-year-old Avedon, it was just beginning.

Far less known today than Hoyningen-Huene’s fashion images and portraits are the images in the books that were published in his lifetime, African Mirage: The Record of a Journey (1938), Egypt (1943), Hellas: A Tribute to Classical Greece (1943), Baalbek/Palmyra (1946) and Mexican Heritage (1946). They’re long out of print but worth seeking out, especially his book on Classical Greece.

Having left Harper’s Bazaar, he lived briefly in Mexico, then travelled to Spain where he made three documentary films, including The Garden of Hieronymus Bosch.

In 1947, he relocated to Southern California and took up a post as a teacher at the Art School Center of Los Angeles. In 1954, he began working as a colour coordinator for George Cukor in Hollywood. The job title doesn’t fully convey the role he had on many films, where his work would sometimes encompass art directing, and designing sets and costumes. A prime example being Cukor’s 1957 film Les Girls, with music and lyrics by Cole Porter, starring Gene Kelly, Mitzi Gaynor, Kay Kendall and Taina Elg. In 2022, Lucy Fife Donaldson, University of St Andrews, posted a film on Vimeo, Tracing the Threads of Influence: George Hoyningen-Huene and Les Girls, analysing his use of source material, paintings by Renoir, Monet, Cezanne and Degas, to select the colours and hues, with the same in-depth knowledge and meticulous planning that characterised the construction of his photographs.

In April 1965, he was interviewed by the University of California for its oral history project and soon afterwards started working on his autobiography with UCLA professor Oreste Pucciani. It was left unfinished at the time of Hoyningen-Huene’s death from a stroke on 12 September 1968.

Tommy Rönngren brings considerable experience to the George Hoyningen-Huene Estate Archives. He co-founded Fotografiska, a centre for photography, in 2008. It opened its first space in Stockholm in 2010, followed by New York and Tallinn in 2019, and Berlin this year. I started by asking Rönngren how he and his wife came to acquire the archive.

About five years ago, I had an interesting conversation with Gert Elfering who owns the Horst Estate. He told me that Hoyningen-Huene had bequeathed his archive to Horst in 1968, and that Richard J. Horst, still owned the archive. The thought of the archive really fascinated me; Hoyningen-Huene’s life story is extraordinary and he had a tremendous impact on photography, one that is still felt today. I started a conversation with Richard and my impression was that he wanted someone to take on the archive who could instigate new cultural projects and help elevate the photographer’s reputation. As I had a track record with Fotografiska, Richard realised that I could do something positive with the archive; my wife and I took it over in 2020 and brought it to Stockholm.

Can you give me an idea of the size of the archive and its contents?

There are a couple of thousand prints in total and a small number of negatives. Unfortunately, most of Hoyningen-Huene’s early negatives were destroyed, possibly in a fire or a flood. One should also remember that the images he shot for Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper’s Bazaar went straight from the studio to the magazines and then went into their respective archives. The material we care for primarily comprises vintage prints and platinum palladium prints made by Sal Lopes and Martin Axon under Horst’s supervision. There are a lot of notes and letters from his Hollywood friends and stars, from when he worked in the film industry. Hoyningen-Huene also kept a scrap book and we try to use all written material to link stories to the various images. We are creating a database, not only listing the material in the archive, but also material that exists in collections at UCLA, USC and the Harvard University Theatre Collection. His prints can also be found in many major museums around the world, for example MoMA, the Met, Centre Pompidou, Musée Carnavalet, and the V&A. And we would like very much like to hear from individuals and smaller organisations who have relevant material in their collections, which we might not yet have discovered.

Hoyningen-Huene was working on an autobiography with Oreste Pucciani. Sadly, it was left unfinished at the time of his death.

Yes, but it’s extant and we have a copy of the manuscript. We used it as a starting point to try to follow in his footsteps. Curator and author Susanna Brown and I were in Los Angeles earlier this year to visit several of the university and museum collections. In the Cinematic Arts Library at the University of Southern California, they have some fantastic letters from his Hollywood friends, stars such as Sophia Loren, Ava Gardner and Katharine Hepburn. At LACMA we viewed the carefully preserved press cuttings relating to the exhibition ‘Huene and the Fashionable Image’ held there in 1970. At the Getty Museum, we were given a great tour behind the scenes to view the wonderful collection in storage, which includes a dozen of his best portraits and fashion studies.

William A. Ewing noted in his book that, at the time of his death, his archive wasn’t really organised as such. There were essentially boxes of material. Did Horst organise it?

Horst divided the material into categories – photographs, letters and so on and produced notes describing the contents. This was however, before digitisation, so we have spent a lot of time scanning as much as possible. We are still scanning at the moment and our aim is to have a digital version of everything. Our website gives a pretty good idea of how we have structured the work.

Horst made posthumous prints of Hoyningen-Huene’s images in the 1980s. Do you know how many images he made prints of, and if so, how many of each?

There’s no precise documentation so it’s very hard to say, although we have some works that are numbered as part of an edition. Horst oversaw the printing of a selection of his own images and Hoyningen-Huene’s images as platinum palladium prints on paper. Some were also produced on cotton by the master printer Martin Axon. I think Horst was inspired in part by what Irving Penn and Robert Mapplethorpe were doing with platinum at around that time. There are also some artists’ proofs that have little related documentation. We have small platinum palladium test prints with no numbers or information on them. A few have other markings on them, from the New York gallery Staley-Wise for instance, but it’s hard to tell exactly how many were made. We try as best we can to gather more information, and speak to gallerists who were around at the time. Richard J. Horst had some platinum palladium prints in editions of 27, to complement a retrospective in St Petersburg.

You have started producing posthumous limited-edition platinum palladium. Keeping in mind that Horst and his son produced prints, how do you navigate that?

We are basing that work on the wishes that Hoyningen-Huene expressed in his letters. We have chosen to only print images not previously printed in editions or shown in exhibitions. We felt that this was extremely important. The prints are large, approximately 70 x 90 cm, so classic images are being presented in a modern way. The editions are small: eight, plus two artists’ proofs. The prints have been very popular, I think partly because of the sublime quality of the platinum palladium prints and also because the glamour and sophistication of early couture fashion is having something of a renaissance. It’s interesting when you show his images to people, many will say, “Oh, I recognize that!”, without knowing the photographer’s name.

French Vogue had a clear-out of prints in the 1980s, and British Vogue pulped practically all their prints in 1942 as part of the war effort. Condé Nast in New York retained most of the Vogue and Vanity Fair archives, of which some has been purchased by the Pinault Collection.

That’s correct, and we’re in touch with them. The exhibition CHRONORAMA opened at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice earlier this year, showcasing more than 400 Condé Nast images recently acquired by Pinault Collection. Among the highlights are some beautiful gelatin silver prints by Hoyningen-Huene, including portraits of Josephine Baker, Serge Lifar and Cary Grant. As for ourselves, we are working on several exhibitions, and there’s new book coming out in 2024, edited by Susanna Brown with contributions from 10 brilliant scholars, offering new perspectives on his work. Lucy Fife Donaldson spent three months in LA researching Hoyningen-Huene’s contribution to Hollywood movies, and her chapter of the book includes a wealth of new research about that part of his career. Very little has happened with Hoyningen-Huene’s photography in more than 30 years so it’s exciting for us to get his work out there.

Last year, you collaborated on an exhibition called In Style, teaming Horst and Hoyningen-Huene at WestLicht in Vienna. And you’re now working on a film about them?

Yes, we are working with Bedlam, producers of The King’s Speech. It’s still in its infancy but is likely to be a streaming series, focused on Hoyningen-Huene and Horst’s lives together in 1930s Paris.

On the subject of film. As far as I can make out, Hoyningen-Huene made three short films in Paris in the 1920s, a fashion documentary for Vogue in 1933, three documentaries in Spain between 1946 and 1950, and then Daphni: Virgin of the Golden Laurels, made in Greece in 1951. How many have survived?

The only surviving film we have found so far is Daphni: Virgin of the Golden Laurels, a 20-minute film in black and white. The film is held in LACMA’s collection. The archivists there are investigating the feasibility of digitising the film, depending of course on its current condition.

You have had the archive since 2020. Have there been surprises along the way?

There have been so many, not least because of all the different contexts he turns up in, all the things he did, the wide variety of people he knew, the extraordinary places he travelled to. He got to know Joseph Pilates in the early 1940s and started doing Pilates himself. He was empowering women to drive cars. He took mescaline with Aldous Huxley. He befriended Oscar-winning stars. He was like a debonair Forrest Gump, popping up all over the place. Following in his footsteps is a fantastic journey and it’s our ambition to collect all the strands of information about him and share his story, because we believe he deserves that.

Text by Michael Diemar

This article was first published in issue 10 of The Classic – a free magazine about classic photography.

The Classic is published in print and digital format.

All issues can be downloaded here :

https://theclassicphotomag.com

George Hoyningen-Huene: Photography, Fashion, Film, edited by Susanna Brown, is published by Thames & Hudson in early 2024.