The writer Gaston Chérau left in November 1911 for Tripoli de Barbarie to “write about” the war between Italy and the Ottoman Empire in Libya for the readers of Le Matin. He took with him a Kodak camera loaned by a friend and revealed himself as a photographer. The historian Pierre Schill has published photographic and written documentation testifying to this singular experience in the book Réveiller l’archive d’une guerre coloniale (Créaphis editions, 2018). He returns in an interview with Dimitris Gkintidis for “Grèce Hebdo ” on the aftermath of Gaston Chérau’s photographic trajectory during the Great War when the writer-photographer was assigned to the Photographic Service of the Eastern Army in Salonica.

Your approach takes as a starting point the experience and the work of photographer Gaston Chérau during the Italo-Libyan war of 1911. He came to Greece a few years later, as part of the French Army throughout World War I. But what does his first visit from France to Libya in 1911 means to him?

The writer Gaston Chérau (1872-1937) was asked at the beginning of November 1911 by Le Matin to go and cover the war which started at the end of September. The newspaper, then one of the most important titles in the Parisian press, already had a special envoy in Tripoli since the beginning of October and the landing of the Italians. Chérau’s “reinforcement” has a double explanation: the first is due to the evolution of the warlike context and the second to the political positioning of the newspaper. After the conquest of coastal cities, the Italians suffered their first setback at the battle of Sciara-Sciat (23-26 Oct.). During these days, soldiers summarily executed several thousand civilians. The revelation of these massacres by journalists present in Tripoli aroused strong emotion in Europe and rekindled the interest of the media for a conquest that Italian propaganda presented as a “military walk”. It is in this context that Le Matin, an italophile daily favorable to conquest, responded to the request of the Italian ambassador in Paris, Tommaso Tittoni, who wished a “famous pen” was sent to produce an account of events favorable to the Italians. The diplomat suggested Gaston Chérau, he appreciated his writing for the newspaper to which he regularly collaborated, notably alongside Colette, in the section “Tales of a Thousand and One Matins”.

Chérau responded favorably to Le Matin’s proposal, because this mission gave him the opportunity to broaden his horizon of inspiration hitherto reduced to the French countryside. The discovery of North Africa also allowed him to satisfy his taste for travel and his curiosity for North Africa which can be inscribed in the orientalist vogue of the time. But the challenge for him was not only based on the exotic nature of the field of inspiration. Because of the prestige associated with the coverage of the war, the mission appeared as a journalistic consecration likely to widen the readership and the notoriety of the writer at the very moment when he was, for the second time, in the running for the Goncourt Award.

Your works and exhibitions on this pioneer of photojournalism seem to refer to the potential but also to the various instrumentalizations of visual production, since the beginnings of the 20th century. To what extent does Gaston Chérau’s work help us to question the relationship between images and society and how did you approach these themes?

The photographic and written documentation (articles but also letters sent to his wife) produced by Gaston Chérau in Tripolitaine that we gathered in the book Reviving the archive of a colonial war is indeed a milestone in the knowledge not only of the unfolding of the war itself – particularly the moment of the implementation of a policy of terror by public hanging – but also of the way in which war correspondents are involved, as actors, in the events for which they are supposed to bear witness.

Analysis of the circulation and editorial uses of the photos of Chérau and the other journalists reveals a veritable “war of images” in which persuasion does not appear as an emanation of the Italian government or its army, but proceeds mechanically. in a more “discreet” way based on the manipulation of war correspondents and the mobilization of popular media vectors – press and postcards.

By immersing ourselves in the work and experience of the reporter-photographer, the archive makes tangible the existential dimension of the experience and its ethical and political issues, how the sensitive man confronted with extreme violence is torn between his mission of rendering account of events, the demands of his newspaper and his instrumentalisation by the belligerent who welcomed him. Because the behind the scenes of the making of the news allows us to measure the share that belongs to each of the protagonists in the construction of the journalistic narrative and the way in which the war correspondent, a singular witness generally little questioned in the historiography of war, engages his responsibility.

This look at the past is also an invitation to question the current challenges of witnessing and fabricating information and disinformation in wartime, especially in their visual dimension. Because at a time of instantaneity and the propagation of information and images outside of any contextualization and understanding framework, this introspection cannot be limited to the sphere of production of current events and concerns the spectators “of misfortunes of war “that we have all become. This dialogue between past and present has taken two forms. The Gaston Chérau archive was first interpreted by artists: by the writers Jérôme Ferrari and Oliver Rohe in their essay To split the hardest heart (Inculte, 2015 and Actes Sud “Babel”, 2017), by the dancer and choreographer Emmanuel Eggermont who drew the solo Strange Fruit and finally by the artist Agnès Geoffray in two works, Les Gisants and Les Regardeurs. The crossed views on this historic source were also presented within the framework of the exhibition To split the hardest heart presented in 2015 and 2016 at the FRAC Alsace and at the Photographic Center of Île-de-France (CPIF) which brought them into resonance with the works of other contemporary artists who have approached, in different warlike contexts, the question of witness and war violence.

To what extent does Gaston Chérau’s view of colonial conflicts fit in or distance himself from a typically exotic approach?

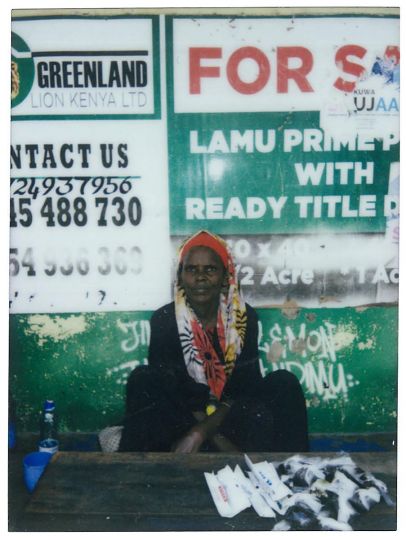

The whole of the photographic report like the writings of the war correspondent and particularly his correspondence is crossed by the question of otherness. The gaze of Gaston Chérau as it emerges from the 230 photographs that we publish is plural. If we follow what he says to his wife through a letter, he himself distinguishes the photos directly related to his mission as a war correspondent from those that have “no warlike interest”. If it is difficult to reconstruct a posteriori these two categories, particularly in the absence of classification made by the operator, one can detect photos “for oneself” in the prints bearing the mark of the naturalist writer wishing to complete the photographic medium his usual written and drawn documentation. When the commercial crossroads of Tripoli appears in all its human and architectural diversity, the report reveals the empire of war on the daily life of an occupied city where the Bedouins came to take refuge from hunger created by the disorganisation of the trade routes. Evoking this component of the report, the historian François Dumasy sees in it “what a number of testimonies of the time, all imbued with the colonial unconscious, had concealed”. In particular the “refugee” nomads, who “haunt part of the Italian archives” but for whom “so far only very few images were available” (Dumasy 2020).

If one were to detect the subjectivity of the operator in this composite set, it would perhaps reside in a double observation: that of the small number of purely landscape photos, while the desert environment or the oases offered a vast visual resource to exotic character and, conversely, that of the frequent presence of children in the photographer’s field. An equally sensitive presence in letters to his wife in which Chérau often evokes the harshness of the living conditions of little Tripolitans in reverse mirror to the privileged life of his young son in Paris.

Your research continues to evolve and, lately, you are orienting yourself among other things to trace the presence and activity of Gaston Chérau in Greece. Can you outline some major steps for us on this journey?

Chérau’s journalistic and photographic experience in Tripolitania was extended during the Great War. The writer was first called upon at the start of the conflict by L’Illustration to cover the German invasion of Belgium and then, from the autumn of 1914, the fighting in northern France and Lorraine. In March 1915, Chérau was mobilized in turn and assigned to a combat regiment in the Nord department. At the end of October 1915, he was posted at his request in the Army Photographic Service (SPA) and left for Salonica and the Eastern Front. Operator then in charge of the section’s direction, he took many photographs on this occasion, particularly during his travels with General Sarrail, commander-in-chief of the Allied armies of the East. The most numerous photographs taken by Chérau between the fall of 1915 and the summer of 1916 relate to the fighting on the Vardar, the withdrawal to Salonica and the Allied camp at Zeitenlick.

The end of the war does not mean breaking ties with Greece. Because in Tripoli, Chérau had met Claude Séon, the consul general of France in the capital of the Ottoman regency. The consulate was for the war correspondent and the other French journalists both a refuge and a place for exchanging information. Before his appointment in 1910 to Tripoli de Barbarie, Claude Séon, born in 1855 in Brousse (Asian Turkey), had been French consul in Salonika (1907-1910). The son of a merchant, he married a Greek Ottoman and he had three daughters. Chérau evokes this “beautiful family” in his letters and also takes a picture of them in the consular residence. As part of our research, Séon’s diplomatic notes to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the French Embassy in Constantinople were important in reconstructing the process of the public hanging of the 14 Bedouins on the Place du Marché au Pain in Tripoli December 6, 1911, narrated and photographed by Chérau.

During the Great War, the game of assignments and events was once again to bring the diplomat and the writer together, but this time in Greece. Claude Séon was indeed recalled to Salonica in December 1913 to become the first French consul in the city which became Greek after the Balkan wars. In his analysis of the French consulate in Salonica, the historian Mathieu Jestin shows how much Séon was part of the notability of the Macedonian metropolis in particular because of the marriage of his wife’s sister with Cléon Hadji-Lazzaro, vice-consul of the United States. Séon held the consular post until 1915, but we have not been able to establish whether the two men met again upon the arrival of Chérau in Salonica in the fall of the same year.

After entering the Goncourt Academy in 1926, Gaston Chérau still had the opportunity to return to the Balkans and Greece twice. In the Balkans, in August and September 1929 to participate to the pilgrimage of veterans of the Eastern Front, both as “Poilu d’Orient” and as special envoy of L’Illustration. His daughter Françoise relates this journey from letters sent by her father: “receptions, overwhelming welcome from the Yugoslav population, pilgrimage to the ossuary of Kaïmatchalan and to French cemeteries, stops of the special train in the smallest stations under avalanches of ‘cheers and flowers’. And a remarkable meeting with King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, thus described by Chérau: “The sovereign was kind to us, addressing everyone with touching interest. He asked me with charming hesitation that I gift him my badge. ”

Chérau had the opportunity to return to Greece in the fall of 1931 in the context of the construction of the Monument to the Unknown Soldier in Athens. The Greek sculptor Costas Dimitriadis, responsible for overseeing the project, invited personalities from the French arts and letters world to express an opinion on a controversial creation. Chérau was part of this “mission” led by his friend the French sculptor Jean Boucher considered, according to art historian Nikoleta Tzani, as an “undisputed specialist in war memorials”. In a letter to Prime Minister Venizelos, the writer praised the bas-relief depicting a dying hoplite produced by Dimitriadis’ assistant, Phocion Roque. Chérau also took advantage of this five-week stay to complete the documentation for a text on Greece and reconnect with Olga and Doria Séon, two of the daughters of the consul installed in Athens. Their friendly relationship continued with the exchange of numerous letters during the first half of the 1930s. The book Le Mulet de Phidias from his trip, published in 1935 (Albin Michel editions), depicts the meeting between a mature Frenchman and two young Greek women under the Attica sky. A nostalgic short story perhaps inspired by his reunion with the daughters of Claude Séon.

* Interview given to Dimitris Gkintidis | Grecehebdo.gr – Published on May 18, 2020.

GrèceHebdo is an edition of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Secretariat of Public Diplomacy, Hellenic Republic.