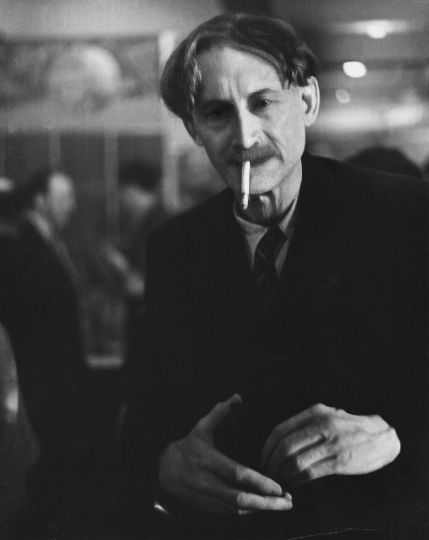

From March 3 through April 16, 2017, La Chambre—an exhibition space and a photography learning center in Strasbourg—hosts Fred Stein’s first solo exhibition in France. A true humanist photographer, Fred Stein captured Paris in the 1930s and New York in the 1940s.

When Peter Stein met us in 2015, we were amazed to discover his father Fred Stein’s images he had brought along. They were vintage press photos, often reframed, which was common practice among professional photographers in the 20th century. Who was this Fred Stein we had never heard of? Who was this American photographer of German-Jewish origin, a socialist and a militant anti-fascist who managed to escape Nazism twice, first in 1933, taking refuge in Paris, then a second time, in 1941, when he migrated to the United States?

The images tell the story of a life caught in the tide of History against the backdrop of two cities—Paris and New York—which the stateless man and his family successively called home. The photographs naturally document places and events, but they also reveal other things, offering a glimpse into the photographer’s mind, his thoughts and ideas. Fred Stein took up photography as a profession out of necessity. Although he was fluent in French, he knew he would not be able to put his education to use and practice law. With no hope of return, Fred and Lilo Stein were forced to adapt and make a living in a country in which they were outsiders and where, as a result, it wasn’t easy to fit in. Fred Stein was an amateur photographer, and since he enjoyed taking pictures, before long he came up with the idea of opening a studio.

Creating their own portrait studio was within their means: the sparse equipment the Steins possessed was enough to furnish a shooting space and a darkroom. With a little bit of luck and a lot of hard work, they built a pool of customers and, later on, began receiving assignment from illustrated magazines. After all, photography was a universal language—something Fred Stein was keenly aware of—and if the talent was there, the photographer’s nationality was of no importance. There were countless photographers from Hungary, Romania, Russia, Germany…—mostly religious, political, or economic refugees—plying their trade in interwar Paris. If Fred Stein got into this business, it was above all in order to survive. He soon learned the ropes, and his portraits began showing something more than faces: they revealed gestures and attitudes, suggested traits of character. But it was above all in the street, among people and events, that Stein invented his own way of telling stories and looking at things, and became an art photographer, in the sense understood today.

Although isolated images and photo stories are hard to sell, as soon as he stepped out of his studio, Fred Stein would aim his lens at the increasingly familiar life of the street and at anonymous crowds. In his Parisian photos, street vendors cross paths with workers, the upper classes with beggars; the faubourgs, Jewish neighborhoods, and suburbs are bustling with activity. Then there are meetings and rallies of the left-wing coalition—images reminiscent of Stein’s subsequent American photographs. Thus, when he came to the United States, he brought with him a considerable experience. He was fascinated with New York City, its imposing architecture, and with its population which was a cross-section of a nation made up of immigrants, displaced persons, and refugees from around the world. “I can capture so much in such a short time,” he declared in one of his talks.

Fred Stein’s photography is a document as well as a commentary. His images express the point of view of an observer capable of lending shape and meaning to individual stories and to anything that caught his eye. Above all, his pictures reflect the empathy and the sense of respectful curiosity of a man sensitive to others’ humanity. Fred Stein realized that the career path he had chosen in Paris had propelled him into the modern era, into the age of the media, and that his future lay right there. He didn’t get to enjoy the belated recognition of his work afforded to other artists of his generation because he died prematurely in 1967. It was only a few years later, in the 1970s, that photographers began to be considered as craftsmen, and even artists. Fred Stein was undoubtedly aware well ahead of his time of the significance of his work, of his oeuvre. A man of deep insight, he quickly sensed that photography could also be a commitment. He understood that, no less than words, images were capable of bearing witness and of asserting a humane and peaceful vision of the world.

Michaël Houlette

Michaël Houlette is Director of the Maison Robert Doisneau and co-curator of the exhibition.

Fred Stein

March 3 to April 16, 2017

La Chambre

4 Place d’Austerlitz

67000 Strasbourg

France

http://www.la-chambre.org/