On the one hand there is an enormous interest in making photographic works that deal with social issues—but there is little money, little interest on the part of publications, and readers are reluctant to pay for serious journalism.

It is, perhaps, the choice of richer societies to withdraw from a discussion of difficult problems—what can be done about them anyway?

Then one meets a blogger from Tunisia, Azyz Amami, for whom there was little possibility of dissociating himself from his country’s problems. For him media became essential in the attempt to transform Tunisia’s government and push it towards democracy. But not the conventional media—he turned to Facebook, Twitter, or whatever social media would not be censored.

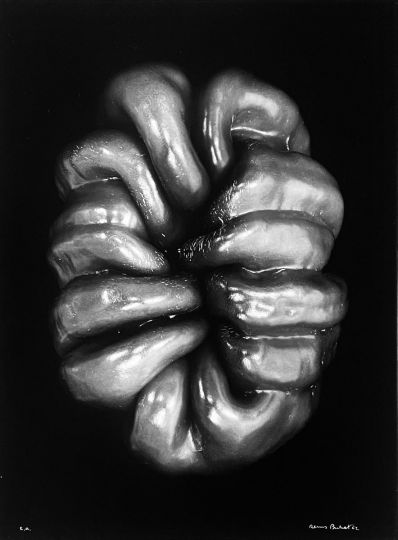

As he put it, the cheap cellphone with a low-resolution camera in it was the “sponsor” of the Tunisian revolution. The photographs were not aesthetically composed and often were taken on the run, but they served to galvanize a sizeable part of the Tunisian public to take to the streets, as well as to alert the world.

He is not enamored of the phrase “citizen journalism,” but instead uses the more democratic term, “open journalism.” Both professionals and amateurs are able to express their differing points of view. And while the Tunisian in the street with a cellphone has to help a wounded comrade, not just take pictures, the professional may be waiting for violence to break out because it is more graphic.

In his case, and that of his fellow Tunisians, the exigencies of life trumped the medium of the photograph. It is an interesting lesson for all of us—it is life that is always more important than any medium, no matter how fascinating. “From Here On,” when applied both to the Arab Spring and to the rest of us, would be quite inspirational.

Fred Ritchin

Fred Ritchin is the director of PixelPress.org, a former editor at the New York Times, and the author of several books