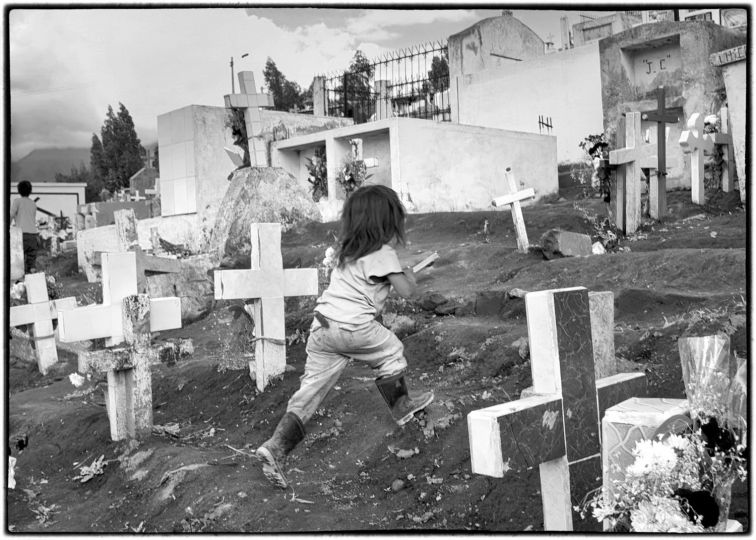

Two black Fashion models look at each other, prominent cheekbones, hair in a chignon with pins, backstage at Lagos Fashion Week. Bubu, the orphaned chimpanzee, jumps about in the trees with the help of a forest ranger in Buba, in Guinea Bissau. Ginika, a young Nigerian woman, sitting in the backseat of a car, with her chef’s hat and rumpled shirt, is preparing to receive her law degree.

This is every day in Africa. Since 2012, the Instagram account Everyday Africa has revealed the beauty and wealth of the continent, with its complexities and subtleties. This photographic project tells the story of ordinary life, far from war, violence, poverty and sickness. If the project is ambitious: to combat the clichés, to stay faraway from the sensationalism and closer to the familiar”, Peter DiCampo, photographer and co-founder, remains a modest man. This American began as a volunteer with the Peace Corps programme in Ghana. His associate, Austin Merrill, too, in Ivory Coast. In four years, they have managed to establish a community of 310,000 fans on Instagram, published more than 3,300 photos, produced by Western artists, but also by Africans.

After several exhibitions, the launch of an educational programme and the ever-growing success on the social networks, comes the desire to produce a book in 2016. For their project, born and developed for social networks, Peter DiCampo and Austin Merrell are going further. There will be a book, a selection of 260 photos, “the goal of the whole social project”, assures Peter. And a “permanent record of a format – Instagram – in perpetual evolution”. Despite the publication of the book “Everyday Africa: 30 photographers re-picturing a continent”, the project will not renounce its origins and will continue to publish on Instagram.

And if they doubted their own popularity, the success in financing the book using crowdfunding should reassure them. The sum of $30,000 they asked for was reached in only twenty days, instead of the forty days that a Kickstarter campaign usually lasts. Peter is still surprised by the enthusiasm. “I know that it’s a very popular programme on social media, but I also realise that the photographic community likes what we do and supports us. Two different successes, both of them enormous.”

Everyday Africa’s strength is in being able to launch constructive debates on a social network, something quite rare in this time of Hatred 2.0. The internet users, themselves, reflect on the photographic and media coverage of Africa. By publishing in physical form, Everyday Africa is not renouncing its origins: its comments and conversations will be integrated into the second part of the book. “We’re also creating a document on how Africa is perceived, how people imagine it and how we communicate today.” The Instagram account has become a space for reflection on African imagery, often tinged with exoticism, with benevolent sentimentalism. At the beginning of the project, when the fan base was essentially composed of young American Instagrammers, remarks such as, “I want to help save the Africans?” were common. “And we ask ourselves, how could this photo provoke this kind of feeling?” Peter joked. As the audience became more African, debates emerged with “more personal” reactions. Of the type “This is the village where I grew up, thanks for showing it.” Then the debates about animal trafficking, the coverage of women’s photography. “It seems to me that we have a duty to retain that”, he summed up.

Peter and Austin are afraid of only scratching the surface of the problem, on a social network. So they created an educational programme, for young Americans “to commit themselves in a deeper way.” To go into schools and confront the teenagers with their own perceptions of Africa and listen to their feelings about the perception of their own community in the media. And finally, the practice of photography, with their own “everyday project”. The book will not remain foreign, it will be, at the same time, both artistic and educational.

Not only for the teenagers but also for journalists: “The problem is going somewhere to look for a particular story”. Peter himself paid the price of this practice when he was producing a report on refugees by searching for “victims and violence”. “If we start with preconceived ideas, we limit ourselves in finding the images. We tend to see only the extremes, and not the whole of daily life in Africa.” But the report is not so gloomy. In art particularly, Parisian exhibitions have shown interest in the charm of African daily life. Seydou Keita at the Grand Palais, his studio where he photographed all of Bamako, the men and the women. Or the Congo Beauty exhibition, in the summer of 2015, at the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, extended thanks to its great success.

Does this popularity of Africa have its roots in a desire for exoticism or is it a really a genuine interest? The problem is truly contemporary and universal. The proof is that the Africa Everyday concept is so inspiring that it has given birth to equivalents is different regions: Asia; Egypt, Jamaica, Latin America, the Middle East, Iraq, the United States and even Iran…

Cécilia Sanchez

https://www.instagram.com/everydayafrica/

http://everydayafrica.tumblr.com/

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/everydayafrica/everyday-africa-the-book