The Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole (MAMC+) releases an impressive book called Collections, recounting the treasures of one of the most important museum in France. In addition to its extensive modern collection, its American minimalist works, its place in the history of design in France, and its various funds like Supports-Surfaces, Fluxus or Arte Povera, the museum has one of the richest and diverse photographic collections in France.

It goes beyond the photographic medium to address multidisciplinary movements, such as Narrative Art represented by Dennis Oppenheim, Peter Hutchinson or Jochen Gerz. Both Narrative Art and Conceptual Art were enriched by historic donations to the museum in the 1980s, thanks in particular to the collectors François and Ninon Robelin and Vicky Rémy. The history of these donations is recounted in an essay by Alexandre Quoi, curator in chief at the MAMC+.

Far from being articulated around several movements, the richness of the MAMC+ photographic collections must be conjugated in the plural. It is not a single movement, nor even a few strong axes, but represents a myriad of established, emerging or experimental artists. The history of this museum adventure is written according to the mutations of Saint-Etienne. Here is a long excerpt, taken from the essay by Nicolas Pierrot, chief curator of heritage and researcher in the Île-de-France Region: “Shifting frontiers. A collection of photographs and the risks of deindustrialisation”.

“The constitution of the collection was, to begin with, part of pioneering movement nationwide. Back in 1964, if collectors Jean and André Fage founded France’s first photography museum in Bièvres, it was not until several decades later that the million images assembled (including a famous collection of amateur photographs) were recognised as being worthy of study and exhibition, and capable of vying with the collection of apparatuses and accessories. The Musée Nicéphore Nièpce in Chalon-sur-Saône, too, was founded around a collection of objects. In 1965, Arles innovated by creating the first photography department within an art museum. Marseille soon followed suite. Next came the Musée d’Orsay in 1978, then the Musée National d’Art Moderne in the mid-1980s. For the medium to be legitimised, it had needed to enter the field of the visual arts, in the wake of pop art and narrative art. Subsequently, the valorisation of “artists using photography” prompted positive reactions from photographers and critics like Michel Nuridsany, who proclaimed the singularity of the photographic approach. It was also necessary that a new generation of historians, moving on from the long-standing inculpation of photography as artistically illegitimate, should take an interest in the specificity of the medium and the “proliferation of its uses”.

Secondly, the first photography collection at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Étienne was noteworthy for its relative concision. True, the heritage from the Musée d’Art et d’Industrie was very modest: 266 photographs collected (and not inventoried) since the late nineteenth century by a few industrialists and connoisseurs. Starting in 1988, the holdings were enriched by between twenty and seventy items a year – no more; in 1996, as the acquisitions process approached a first short hiatus, the collection numbered 855 pieces. Its architects had put the emphasis on auteur photography and constructed coherent series around thematic choices. For the FRAC collection, for example, Jean-François Chevrier had begun by focusing on the theme of the body, which he soon linked with that of the worlds of work. Although not exclusive, these themes offered the starting point – and recurring motifs – on a path between different photographic approaches and continents, presented as described below by Martine Dancer in the first catalogue of the collection in 2005, and lavishly followed up in that of 2007.

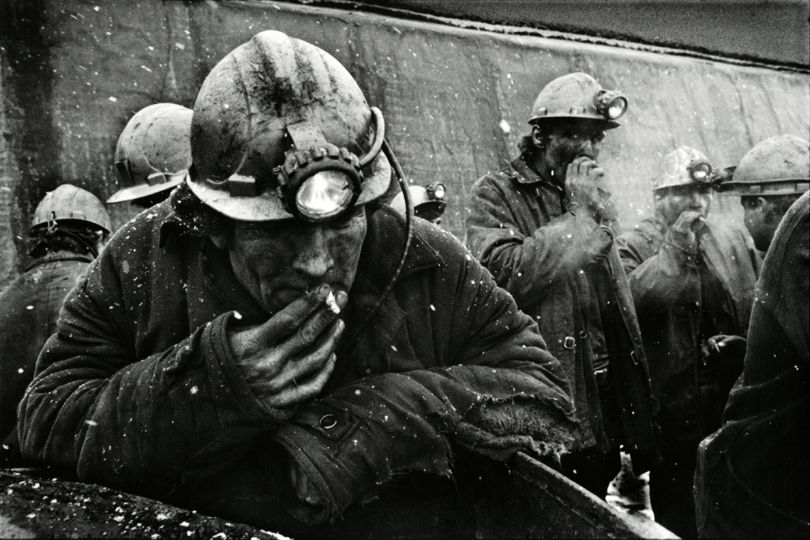

The sensitive figure of Raoul Hausmann gets the ball rolling. The sixty-nine prints from the “emotional” cameraman, who in the 1930s refused the posture of his “oppressive photographer”, offer a stylised inventory of the immediate surroundings – absorbing dunes, moors and naked women’s bodies on the beach – and go on up to the experimental abstraction of his post-war photograms. The path of abstract photography is followed by Laure Albin-Guillot and Peter Keetmann in 1950, in the form of a striking woman diver making a chevron pattern against a beach of white pebbles. This sensitivity to abstraction is evident, too, in the work of certain photographers interested in the world of work. Many of the vintage photographs of factories in the 1930s taken by Piet Zwart, who was very close to the De Stijl movement, feature tight framing designed to achieve “technical beauty” through the play of decontextualised forms; and, among those of René-Jacques (at Renault) and Peter Keetmann (at Volkswagen) in the 1950s, the details of the sheet metal rolled or hammered form waves or eddies. The point being that these photographers are not hostile to a form of “subjective photography” which “privileges the pared-down form of description rather than the narrative form of amateur photography”. In counterpoint, humanist photography, too, features in the collection, ranging from the work of unidentified photographers to that of the great Walker Evans, whose “very enigmatic portrait of a woman, who seems absent from the world, [taken] unwittingly in the subway”, contrasts with his well-known and engaged documentary style and is one of the collection’s masterpieces. The documentary style, indeed, displays the formal quality and violence of its gaze in Hands of a Seriously Injured Soldier (1946) by August Sander. To capture the dramas and joys of the post-war years – this was the role also taken upon themselves by advertising and journalism which, during the 1950s, both in the East (Vaclav Jiru and Jan Lukas in Czechoslovakia) and in the West (René-Jacques, Federico Patellani) offered a source of income and field of expression to many portraitists.

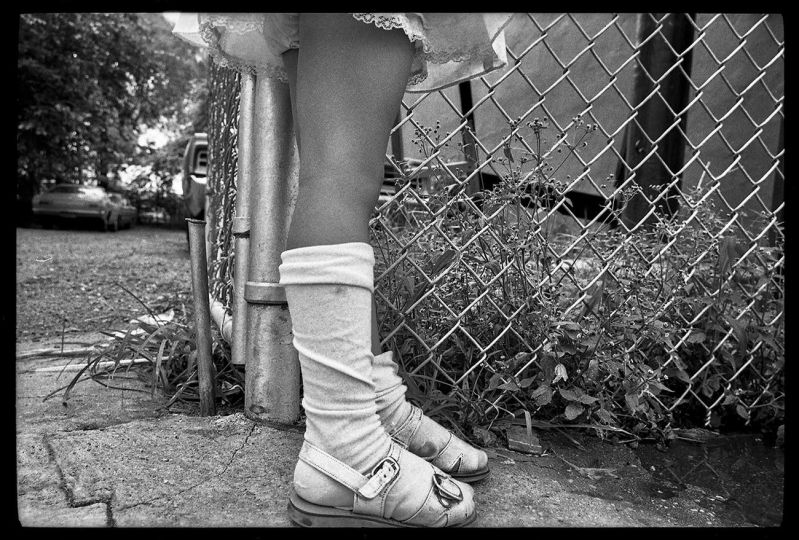

Ultimately, though, it is man’s relation to his urban environment that dominates the collection. One thinks of Lisette Modell who, in the 1950s, opted for a granular, blurred finish to captures the excesses of urban life in the hubbub, crowds and feverishness of New York; one thinks of the London bankers by Robert Frank or the neglected black neighbourhoods of New York by Helen Levitt; of the quasi-ethnographic and brutalist gaze of Nigel Henderson – a member of the Independent Group – on the unemployed youth of London’s East End; and, in more extreme territories, of Larry Clark’s portfolio of young Americans beached in a slough of drugs, alcohol and sex after the illusory euphoria of the sixties.

Finally, and as promised, this first collection pays homage to its chosen territory. Subtly so. “I have avoided regionalism,” rejoiced Jean-François Chevrier in 2005, when Michel Thiollière, the senator, mayor of Saint-Étienne and president of Saint-Étienne Metropole, remarked that he “appreciated the presence in the collection of vintage photographs that bear witness to the history of our region”. This is because the strategy consisted, not in assembling a corpus of regional views, but in distinguishing local talents. In 1995 there was a rediscovery of Félix Thiollier – after he was recognised by MoMA – not for the documentary values of his views of rural and industrial Forez, but for his romanticism and the depth of his blacks. Gunther Förg’s view of Saint-Étienne’s “houses without windows” were brought into play to help revalorise the city’s heritage at last. In 1996 the museum pulled off a coup with the acquisition of a composition specially conceived for the museum by Bernd and Hilla Becher, a study of the “Marseille” pithead at Chambon-sur-Lignon as part of their typology of mine-head frames. There was also an interest in several photographers working in the territory, like Jean-Louis Schoellkopf and Yves Bresson. More generally, the theme of work and industry, extending that of the body, resonated with the economic history of this mining basin that had entered a process of major change.

Opening up disciplines

On this light but solid foundation, the development of the collection entered a new phase after 2000, following three directions determined, variously, by specific credits, new relations and donations. The first concern was to encourage the dialogue between disciplines, supports and mediums by including contemporary installations that included photography, whether analogue or digital. This was made possible when the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations donated installations by Christian Boltanski, Jean-Marc Bustamante and Ange Leccia in 2006. The museum also acquired several works by Nan Goldin (1998), Cindy Sherman (1999) and Gilbert & George, before going on to a new generation of contemporary photographers represented by the likes of Jean-Pierre Khazem and Nicole Tran Ba Vang.

At the same time, it was necessary to closely follow the contemporary reassessment of the uses, social function and values of photography. In this regard, the acquisition of over 4,500 photographs from the Paul Martial advertising studio (1930s–1950s) was, for Martine Dancer, a “bit of a gamble”: these prolific images of the industrial world, which had previously been confined to archives, libraries and societal museums, now entered the Musée d’Art Moderne. The logic of this acquisition was in line with the one that saw the museum integrate the library of Jean Laude, which includes books by creative photographers such as Brassaï (Paris la nuit), Ed van der Elsken, Ed Ruscha and William Klein, as well as volumes such as François Kollar’s La France travaille, the books of Blanc and Demilly and even commercial journals. Since then, these images have played an essential role alongside the collection’s other vintage prints in the museum’s multidisciplinary exhibitions, in a kind of “synthesis of the arts”, which opens up presentations that were once closed and questions the fictive hierarchy between the discourse on artworks and the interpretation of documents.

But I would like to end on the subject of auteur photography, which the museum never rejected – especially where local talents were concerned. After the body theme came that of work, then that of the urban environment. The collection could now be opened up to modern architectural photography. In 1999, after his exhibition at the museum, Ito Josué gifted 123 prints from his Publics series, made with Louis Caterin. These showed the faces and expressions of spectators at Jean Dasté’s open-air theatre, standing out against the urban background in the half-light, captured during the period of decentralisation of French theatre. Three years later, Ito Josué began the progressive donation of 970 negatives, covering the area’s old mining sites and the architectural projects developed there in the later modern period (especially Firminy-Vert where Le Corbusier was active), which were now becoming part of the heritage. In 2018 coverage of this theme was enriched by the acquisition of Rajak Ohanian’s remarkable photographs of the Cité des étoiles de Givors de Jean Renaudie, taken in 1974 and offering another vision of the architectural transformations of the metropolitan territory. In counterpoint, the three large works by Roselyne Titaud from her Oktogon series, made in a big Berlin hotel in 2011, offer a meditative pendant to these high-rise, proliferating structures in the outer city. Finally, it was only natural that the museum should exhibit Valérie Jouve, a famous local daughter whose creative development has reached well beyond her territorial roots in its scope and significance. By going from red to green, by switching her gaze from the light of dead stars – those of the industrial city – to the deeply lined bark at the foot of tree trunks, she forges the vital link between the trauma of loss and the hope of a new world.”

Nicolas Pierrot

Collections

Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole (MAMC), 2021.

Published with Snoeck Publishers. Directed by Alexandre Quoi, curator in chief and Aurélie Voltz, director.

Graphic Design by Catherine Barluet and Corinne Thevenon.

350 pages, 39 €.

Available in April 15, 2021.