A collection can have a lot to do with the indeterminacy principle. And you might say: what does a quantum physics formula have to do with a collection of photographs? It has much to do with it. Just like scuba diving in the darkness of caves and the study of the self and of one’s identity has. A collection of photographs is much more complex than a collection of images. But let us introduce Ettore Molinario: he is the collector, the protagonist and the driving force behind his collection. He sought out photograph after photograph, suggestion after suggestion. Thus, one by one, like living elements, the images took their place in the collection, which is a dynamic reality in constant motion. It’s never definitive.

At the age of 50, Ettore Molinario decided on a radical change in his life: he left high finance to follow one of his passions: “I re-enrolled at university, majoring in art. Exactly what I would have chosen when I was young. Then I spent three years on a very personal Grand Tour, made up of museums and original artworks”. Perhaps today, in the presence of a phenomenon like AI, we are even more aware of the role of “the original image”, of seeing from the real, as opposed to the reproduction (a subject that has always interested critics of art and aesthetics).

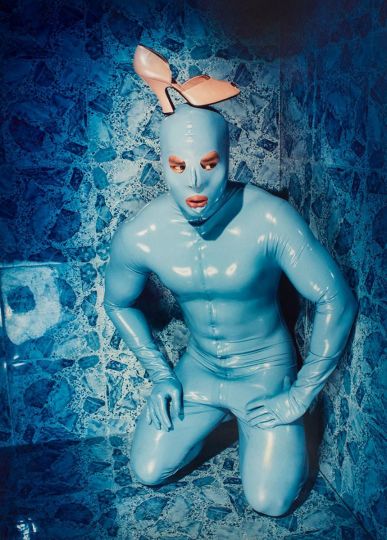

“Looking at the original works is like an encounter with them, so that they become part of us”, both at the level of rational knowledge and at the level of introjected perception. It is something that lingers in the mind and emerges in the search for other images or in chance encounters with some of them, not too dissimilar to what happens in life. And so it was that the encounter with a work by Van Gogh, with its spectacular inversion of colours, triggered connections with images encountered during a second Grand Tour through photographic images and then with others, equally disruptive in terms of colour perception, such as Shoe Story by David LaChapelle or Disguised portrait I (from “Fetish of the Image” Series”) by Agata Wieczorek.

Ettore Molinario’s is an “autobiographical” collection. “I don’t know how to photograph, but the great photographers take photographs also for me”, he says. The collector’s proactive action at this point consists of the search for works, which, like pieces of a mosaic, will make up the whole; “they reassemble my image, reconnecting the cold, rational, visionary part of me and the more lonely, sometimes melancholic part of me that seeks immersion in art. Photography is an accomplice in this quest of mine because it has helped me and still helps me reassemble the fragments of my identity, both defined and fluid. I reflect myself in the images in my collection and I choose them because I identify with them”, he explains.

Chance and research intersect to compose a whole in which the works dialogue with each other, following submerged archetypal meanders, from which individual images emerge, connected subterraneously like the islands of an atoll. Each fragment, each photograph, is therefore essential to this recomposition, in which memory also plays a strong role in suggesting correspondences and affinities (more and less evident or even submerged), proximity and distance of times and places. An explicit reference and “homage to Aby Warburg and the pages of his Atlas”, Ettore Molinario adds.

“The desire to explore the darkness of the unconscious” is the underlying theme of his collection, which is referred to as “parts of me” (the tiles of the mosaic, in fact). But for Ettore Molinario the action of collecting is also akin to exploration as a physical and psychoanalytical experience at the same time. Again, an intriguing interweaving of different sensations and impulses, which highlights the close bond between the collector and his collection. According to him, the search through the infinity of available images (not only author’s images, but also anonymous ones) has a parallel with the practice of cave diving, an exploration that allows him to experience, even dangerously, the themes of his collection. The sense of the limit as well as the fascination of extreme danger, the tension of the unknown, the presence of the shadow of death and the pleasure of dominating it.

There is the vertigo of the abyss in the depths of the earth, when diving, as he has been done for years, in the cenotes of the Yucatan peninsula, natural pools sacred to the Mayas, who considered them as entrances to the ‘subterranean world’. Here it is necessary to light a torch to cut through the shrouding darkness. It is a replicable experience in collecting: this time it is photography (which by its very genesis is created by light) that is needed to see into the darkness of the self.

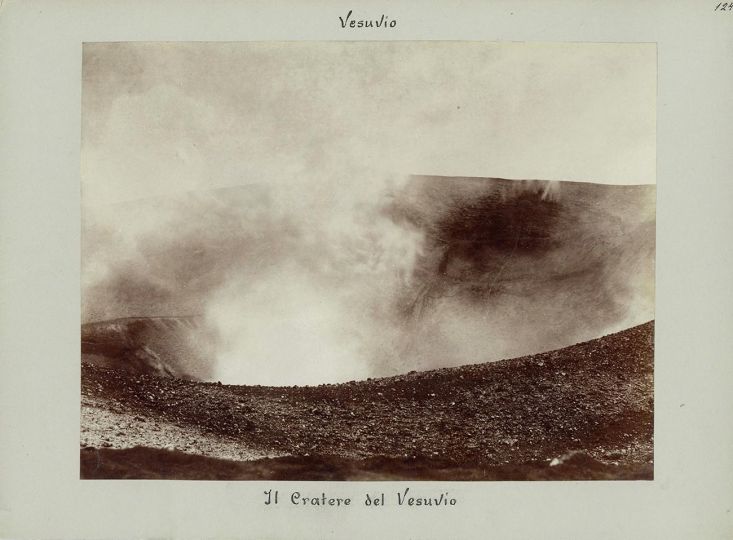

“The first dive I took, he says, was in the pages of Journey to the Centre of the Earth”. By the way, although Jules Verne makes little mention of photography in his novels, he must have known it quite well, since Nadar was a friend of his. He shared with him a passion for flight and founded the Société d’encouragement de la locomotion aérienne au moyen du plus lourd que l’air. Whatever the case, Ettore Molinario says: “Thanks to the French novelist I have become a marine speleologist and a collector of photographs, which are synonyms for me”. The journey begins in the crater of the Snæffels volcano in Iceland and ends on the island of Stromboli in Italy. But it is the crater of Vesuvius, as portrayed by Fratelli Alinari, that sums up “my dreams, my obsessions and the concreteness of reality. The abyss made me pass through all my ages in an instant. In dialogue with it, there is another image, closely connected to the volcano and the Grand Tour: the Roman Amphitheatre of Pompeii by Giorgio Sommer. Every time an image is added to the collection, it is a challenge”, a combination that creates interesting connections between the photographs, changing the collection as a whole.

Here, then, is the indeterminacy principle. Heisenberg demonstrated that it is not possible to know two conjugate variables (referring to subatomic particles) at the same time, except with an uncertainty. As mentioned above, the relationship between the collector, Ettore Molinario, and his collection, with the images that make it up (“parts of himself”), is a symbiotic one. But the relationships between the parts change every time he looks at the images, and with each new photograph that enters the collection.

Thus, with due differentiation, it is impossible to determine the “position” of an image in the collection with any degree of precision, because attempting to do so (or even just observing it) creates a perturbation in the system. This opens the way to ever new perspectives. But that is a subject for another time.

Paola Sammartano

Collezione Ettore Molinario

https://collezionemolinario.com