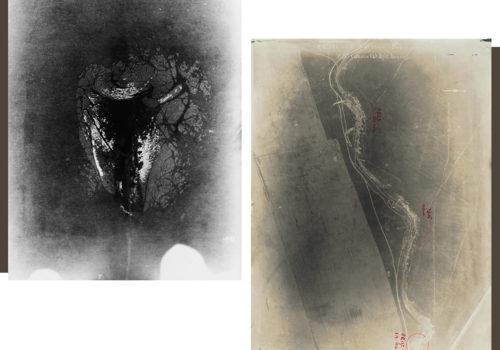

This is the twenty-eigth dialogue from the Ettore Molinario Collection. A dialogue born from the entry into the collection of one of the greatest Italian artists, Paolo Gioli, precisely forty years after his famous exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1983. In a mirror more than in a dialogue this time, since the images look so alike. There are two chasms, two trenches to penetrate the world of eros and thanatos.

June 26, 1917 was one of the many days of the First World War. The American ships had arrived at the port of Saint-Nazaire, in Brittany, and had unloaded the first fourteen thousand soldiers, ready for the massacre. On the Italian front, the Alpine troops were fighting the famous Battle of Ortigara against the Austrians. In Romania, at eight in the morning, pilot-sergeant Iliescu was flying at an altitude of 2,100 meters and from that height sub-lieutenant-observer Ioanid had photographed a very long trench. From the plane it looked like a river watering the fields; a thin road ran parallel to the watercourse then divided and along the hypotenuse it joined the corners of an imaginary triangle. There was no trace of the men who lived in that furrow dug in the earth, zigzagging every ten meters to prevent a shot from targeting the entire trench. Cries, desperation, illness, and death did not reach the sky. Too heavy, too dense. It was the censorship of heights, a way of distancing oneself from the war and its horror.

Already in 1859 Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known as Nadar, had photographed Paris from above, taking a camera with him on board a balloon. But when in the same year Napoleon III offered him fifty thousand francs to create an aerial topography of the military campaign in Italy, Nadar declined. Fantasising, we can imagine the reason: Nadar, the great master of the portrait, the man who represented men and women as monuments to life, with those bodies, those faces, those looks so true, that man could not tolerate being at the service of those who, using photography, would have destined those same bodies to suffering. It happened almost a hundred years before Robert Oppenheimer’s moral drama, the genius who in the aftermath of the explosion of the atomic bomb said of himself «now I have become Death, the destroyer of worlds». Nadar made his choice. In his way he was a pacifist.

In the realm of imaginary correspondences, Nadar would have loved Paolo Gioli’s work very much, because no other artist like Gioli has explored not only the mystery and beauty of the body, but the time to capture it – in his famous Photofinish – and the distance to enhance the material, dark and threatening in the Sconosciuti, carnal in the magnificent Naturae, to which the image in the collection belongs. Resetting the coordinates of space and opening up to another depth of field, Paolo Gioli had placed a blank sheet of paper on a body and in the darkness of his studio he had illuminated it with a flash. The extremely violent light, nearly like an explosion, had crossed the paper, revealing through contact what it had encountered: a vulva, its heart-shaped lips, its humours, its hairy buds, and that black void that attracts and multiplies the life and the fear of living. Another trench in which to sink, a warm trench of woman and nature-wife in which to enjoy and die. This is the anguish of men who in times of peace immerse themselves in the female abyss and in war seek it by digging the earth.

Ettore Molinario

www.collezionemolinario.com