Back in ‘93, Estevan Oriol was tour manager for House of Pain. His father, a photographer, Eriberto Oriol gave his son a camera, told him to take pictures. Oriol remembers feeling weird about it. “Most people with cameras were paparazzi or tourists. They take out the camera for everything and nothing. I don’t want to look like that. Even now I sorta feel weird taking it out,” he reveals.

Oriol always loved cars and the lowrider culture of Los Angeles. In 1989 he purchased a 1964 Chevy Impala from a friend for $1500. Over the years he put in work, rebuilding it to its original glory. Over the years the car has had four different looks; he is currently working on a fifth edition.

This kind of dedication comes to someone with a love for the tactile, the machinery of our age, the car, the camera. Both are integral to his work. He describes Los Angeles as his canvas, as he sets forth around the city taking pictures along the way. He explains, “My Los Angeles is the beaches, mountains, everything. Beverly Hills, Hollywood, South Central, East LA, Downtown. There re so many different parts of it. I go everywhere. That’s a 300-page book right there.”

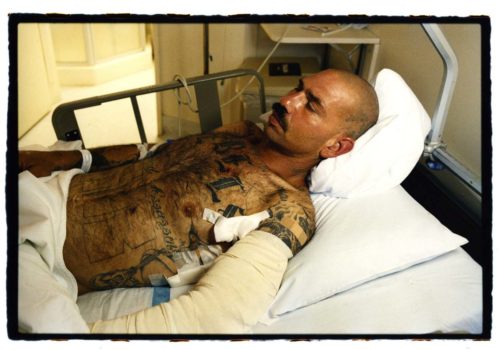

Indeed, Oriol’s filing cabinets are spilling with images, photographs going back two decades of Los Angeles, it’s residents, it’s landscape, it’s culture. And from this diverse backdrop, he is currently culling a selection of images for publication in his second monograph, Portraiture of Los Angeles (Drago). This book focuses on gang culture, a way of life that he has seen from the inside. Oriol observes, “You got cool guys, crazy guys, assholes. Most people are cool that’s why I hang out with them. It’s more a brotherhood, the family. Got the barbecue, lowriding, hanging out, school days, guns, drugs, a little bit of everything.”

And then there is style, culture, pride, a way of life that Oriol embodies as a self taught artist navigating any number of industries using the photograph. He laments on the death of magazines, as we all do, those grand days where archives were open for editors looking for classic and cutting edge work. Now Oriol is thinking about how to share his work with the world.

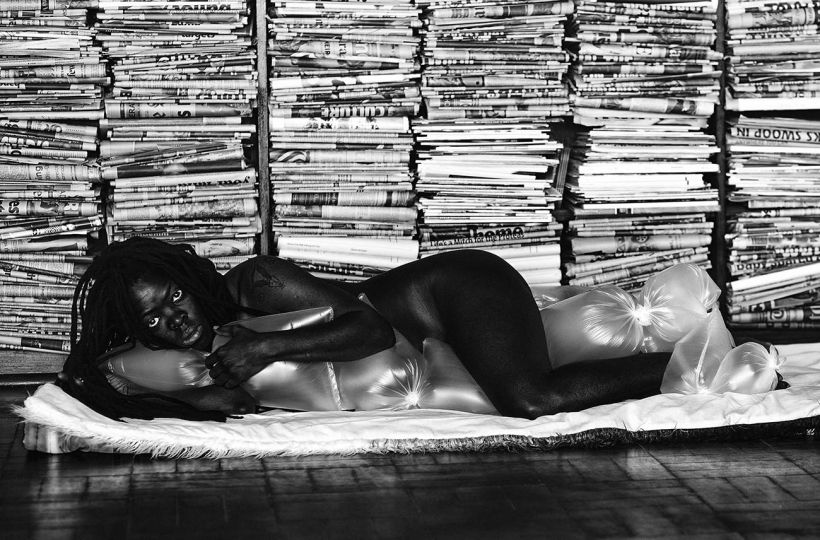

“I’m doing the book so that people who can’t afford prints can buy the book. I ended up making products: calendars, playing cards, t-shirts. Not everyone wants t-shirts. People buy books and put them in their library. I want people to buy my books. I imagine a 60 year old man is walking through the airport and he sees the cover of my book, L.A, Woman, and he wants to get it because of that.”

That, in fact, is exactly what happened to Oriol in Italy, while promoting LA Woman in Italy. He asked them if they knew his other work. His iconic “L.A. Fingers” or the lowrider/gang portraits that have dramatized his black and white work for years. The old man knew neither. He just knew what he liked: the ladies.

L.A. Woman is Oriol’s love poem to the girls and the gun molls, the gansta bitches and the baby dolls. It is around the way girls from the City of Angels, forever cast in film noir they are vixenish kittens prancing before the lens. Oriol’s women come hither on every page.

Oriol’s women have brought him success, and now as he prepares for his second book, he can reflect upon what it’s all about. We talk about the way it was back in the days, when gangstas all dressed in a way that represented their neighborhood, until that became a tool by which the LAPD would oppress their civil rights, with injunctions passed against public assembly of three or more people. We talk about police harassment, search and seizure, police brutality. We talk about how you reach a point in your life where you can’t be hanging out. Oriol is a grandfather. He’s building a legacy.

Miss Rosen