“A photograph is an entity. You don’t crop it, you don’t butcher it, you don’t plaster text over it, you treat it with dignity.”

Elisabeth Biondi has left an indelible impression on all of us throughout her powerful career at four of the most influential magazines in the world. Biondi joined The New Yorker Magazine as Visuals Editor in 1996, just a couple of years after photography had first been introduced into the three quarters of a century old magazine. From her extensive background at Geo, Stern, and Vanity Fair, she brought her masterful eye to The New Yorker, helping to build their reputation for their award winning use of photography.

I spoke with Ms. Biondi in her Condé Nast office, high above Times Square:

From Germany / to America

I left my village in Germany when I was 19. It was a small village, only forty-two houses, two hundred people and four hundred cows. I went to Paris, and then London as an au pair girl. I didn’t really study photography. I was ready to leave Germany and looking to immigrate somewhere. You could go to Australia, South Africa, or Canada if you paid 200 marks, which is about $50.00, and commit yourself to stay in the country for a period of time. They were looking for immigrants, especially Germans, for some reason. I asked for the forms and I was debating where I was going to go. Canada was too cold for me, South Africa had political problems and Australia didn’t really entice me. I was going to do one of those three, when I met my American husband in Frankfurt while I was working for Lufthansa.

We stayed for a year in Germany after we had married, then we came to New York. He worked as an assistant Art Director at London Records. I wanted a job, so he said there’s this job in a photo studio and I went to interview.

It was just a little studio with staff photographers. We produced shoots, a ‘stock’ library, and carried out assignments. It was a very different time, the late 1960’s, early 1970’s. Our photography studio produced magazine covers; they did assignments, anything and everything. I was the assistant to the man who ran the company and I got my basic training how this was done. At some point while working there, I decided I wanted to work for magazines, and I wanted to be a Picture Editor.

Picture Editor / Geo Magazine

I went to a magazine to get the experience – I don’t want to reveal the name – then I waited until I found a magazine that interested me. German Geo

decided to have an American magazine on the American market. It was supposed to be a more contemporary National Geographic and modeled after the very successful German Geo. With the combination of my being German, and now having the title ‘Picture Editor’, which I really wasn’t, I was hired as the assistant Picture Editor. Alice George was the Picture Editor. There was a big upheaval at the magazine fairly early on and I was named Picture Editor. When I joined the staff of Geo I was divorcing, it was an emotional time for me and Geo became my home.

At Geo, Thomas Hoepker was the Executive Editor, in charge of visuals and layout. He is a Magnum photographer now, and my training came from him. I learned from a photographer, and certain basic understandings or rules, if you want, from this time have stayed with me my entire work life; “A photograph is an entity. You don’t crop it, you don’t butcher it, you don’t plaster text over it, you treat it with dignity. You look at it as important as you treat words. It has different properties to it, but it isn’t simply an illustration.”

It was the Magnum time. The premise was, photographers would be sent off for three or four weeks to tell a story with or without a writer, to photograph a story.

They would come back and make a presentation to us. We would make an edit and then the visual treatment to the magazine would be put in layout. In some way, the visual treatment was as important, if not more important, than the text. In the beginning, it was more photography driven. Over the years, it changed. In the end, it became more like a travel magazine but the initial premise was not unlike National Geographic— that you could tell stories in the photographs. In our first issue, we did the Badlands. It was more than thirty pages of exceptional photography. Usually we published six stories — some were large, some slightly less, but it was always a sumptuous display of good photography.

From Geo / To Vanity Fair

Vanity Fair was then edited by Tina Brown. It was the early years, it wasn’t successful yet. She had already been there for two years and Annie (Leibovitz) was already present at the publication. Vanity Fair was very different from many other publications—-basically Tina didn’t make a judgment between words and pictures. Whatever was interesting, or as she would say, “Hot. Hot. Hot. Hot. Hot!”, got more space and was promoted.

Certainly there were the important word pieces, but photos were important too, and they contributed to it’s success. I would say there was a Vanity Fair style of photography, particularly portrait photography. I think Annie was a big part of that, and it helped make Vanity Fair successful. One of the early success’s was Harry Benson photographing the Reagan’s in the White House dancing. That was a coup and was noticed. And then of course Helmut (Newton) shooting Claus von Bülow, which was much talked about.

I was there for seven years. It was time for a change. I moved back to Germany and went to Stern.

Return to Germany / Stern Magazine

From 1968-1996, I was in the U.S. exactly 23 years. I came when I was 23, and I went back when I was 46. Half my life was spent here and half my life was spent there. I really had not kept up with my German life. I came here to immerse myself in all things American and I stayed away from everything German. And it was hard, it was really difficult being in Germany, working for a big fat weekly, because before I didn’t read in German, I didn’t know German politics anymore, I didn’t know German TV. When I was in the U.S. I didn’t see Fassbinder, just to illustrate how much I had focused on giving up my past. German popular culture was alien to me, it was all an enormous challenge. But in the end, I reconnected with Germany—with my past, with German literature, and German films, and that was terrific and great. I am so grateful for the opportunity.

Stern is a weekly magazine: a combination of Newsweek, Life Magazine, Paris Match, not the way it is now, but Paris Match at that time, and the London Sunday times a little bit. It was a mixture of hard news and soft news. There was usually a big portfolio feature, news in front, and then celebrity coverage. Visually it was mainly photography, and illustration was minor. I’d never worked for a weekly magazine before. After three quarters of a year, I had information overload, nothing would go in my brain anymore.

We had 15 staff photographers, but in some way that model had outlived itself. Originally it made sense, but the photography world grew bigger and one could hire photographers all over the world and have access to everyone, so it was a changing time. You worked with freelance people as much as you worked with staff people. I stayed five years.

Return to America / The New Yorker

I decided I wanted to go back to America. I’d been in Germany five years. At first it was all new and fresh and then I got used to it and decided I really preferred to live in America. I thought I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in Germany. I decided I was going to leave when I got a phone call from Pamela McCarthy, the deputy editor at the New Yorker and she said, “Have you thought about coming back to America?” “As a matter of fact I have”, I said. It all happened very quickly after that conversation. It was the only time in my life something happened I really wanted, without doing anything for it.

Tina had already been at the New Yorker for a few years. I came at the time when she decided to have a proper photo department in a more conventional sense, i.e. like other magazines had, and that’s when she hired me.

Photography first came into the New Yorker in 1992, of a fabulous full-page photograph of Malcolm X by Richard Avedon. At the beginning he was the only photographer. I think it was a very smart choice. He introduced New Yorker readers to photography gradually. It was a really smart decision Tina made. And then it evolved and we added other photographers. It’s really hard to do a weekly with one photographer who was prominent and very busy. It just naturally evolved.

The challenge for me was to help develop a language in photography that suited the New Yorker, which is and was a text magazine. It’s a natural with Richard Avedon; he sets the tone of the magazine. He’s sophisticated and the magazine is sophisticated, so that’s sort of a no brainer in a way. Then if you open it up, I think at first it was done by doing, rather than sitting down and planning what photography should be in the New Yorker.

I think magazines change all the time and I’m sure if I looked at the New-Yorker from ten years ago, the photography, I would say it was different then, but there was never a decision to make it categorically different, it just evolved. And one always needs to think about it and to change things before readers get bored. One has to always be ahead of the reader.

I was friend with Helmut Newton from Vanity Fair. It was great to have him work for the New Yorker. We had to find the right stories for Helmut to photograph for the New Yorker and we did. I think Helmut was a great portrait photographer, and oddly enough his male pictures were as strong, if not stronger than his pictures of women. They were psychological.

And Robert Polidori is a great artist, great photographer. His big story was Havana. The book is in its third or fourth printing and has become a classic. Basically it was not a challenge to get the people to work for us. Even though we didn’t use a lot of pictures, photographers like to work for us. It’s prestigious to be published in the New Yorker. I think most photographers are very happy to work with us. It’s wonderful. And I work very hard to make new photographers understand the New Yorker.

When I work with photographers, it’s a collaborative process. My job is to translate the magazine to the photographer and the photographer to the magazine. It’s what I see as my role. I believe very much that personality is a factor, in addition to talent. I want to know the photographer so I can pair him with the right person for portraiture, for example. We work with artists, we work with photojournalists, we work with portrait and still life photographers. I’ve worked with all these different disciplines, if you want to call it that, and I love diversity.

Collecting Photography

When you look at my Collection it’s pretty much like my wall. I’m not saying the same pictures, they connect to my personal experiences. Often photographers ask me if they can give me a photograph – and then I think very hard about it, which one I want to live with. The pictures I’ve bought myself are all very personal, all pictures I like for personal reasons. I never thought about building a Collection, they are just my photographs and they are interesting and take different directions. Very few still life’s, but other than that, there’s a little bit of everything.

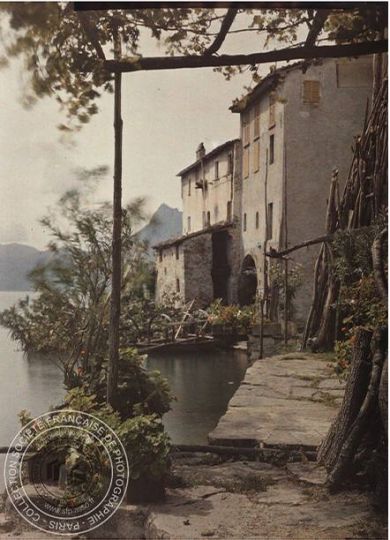

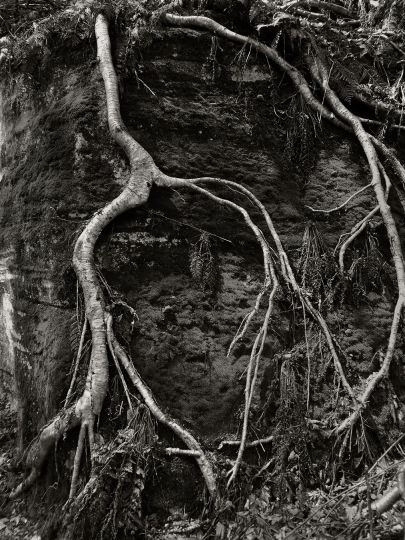

The ones that are on my wall are there for different reasons, sometimes I like the pictures, sometimes I like the picture and it was special to work on it, or because the photographers were important in my life, like those two guys (pointing to a photo of Helmut Newton and Richard Avedon together). I came across the picture by chance. And that’s a Helmut up there, the naked woman (image in portfolio). Helmut was so German and this picture is so German. It’s one of my favorites. I grew up in the woods. Only a German can make this picture.

Elisabeth Biondi is leaving The New Yorker March 15. She is curating an exhibition for the New York Photo Festival in May 2011.

–Elizabeth Avedon