Synonymous with the art of travel since 1854, Louis Vuitton continues to add titles to its “Fashion Eye” collection. Each book evokes a city, region or country, seen through the eyes of a photographer. Jonathann Llense’s journey to the island of Tahiti is anything but an exotic adventure, thwarting stereotypes of elsewhere.

To open Tahiti is immediately to feel a kind of lightness and laughter, or at least a distance, from the paradisiacal representation that has long characterized Tahiti. The largest of the French Polynesian islands is a full day’s flight away. In the Western imagination, it figures prominently in the Olympus of idealized lands. First it was James Cook’s notebooks and Louis Antoine de Bougainville’s accounts, then gradually the myth of original purity in the 19th century fantasized by Enlightenment thinkers (Diderot in particular). Western imagery turned the island into a land of color and harmony (Gauguin in particular, who became famous on the island for his personal vices).

At first, photography helped to document the lives of local communities in more concrete terms – the Albert Khan collection is a good example of this – but from the 1960s onwards, with the rise of mass tourism, the island became a commercial idealization of paradise: fine white sand, crystal-clear waters, endless beaches, waterfalls and abundant, bushy vegetation amid shimmering flowers. All suggesting a gentle life, set back from the madness of the world.

This is not the case. We now know that the social and political situation of the Polynesian islands is made fragile by their remoteness from metropolitan France and the disengagement of the French state, by their economy based on fishing and tourism, and by the persistence of a myth fed by colonial representation. It’s a backdrop well understood by Jonathan Llense, who uses his photographs to poke fun at the island’s clichés and banalities.

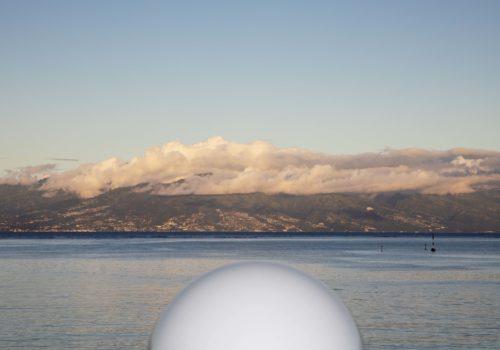

The book opens with a large view of the lagoon, like a horizon promising appeasement and contemplation, but the image is as if obstructed by a large hand (the photographer’s?). Elsewhere, the fin of a concrete shark ruins another sea view, while light-heartedly mocking the shoddy tourist sculptures on the beachfront. Again, a finger points at nothing from an aerial view, incongruously ruining a wide shot. The device is repeated several times, as if to discourage the very idea of exoticism.

The photographer’s intention is to make use of tourist photography, to consciously exploit its possible mistakes and, above all, to mock its objects of interest.

This mockery, gentle and without much malice, takes over tourist objects and other trinkets: flower necklaces drying out, pineapple stickers, “Mme Doux” rum bottles… Humans are everywhere, without ever being taken head-on. In their traces, in their consumption, in their entertainment, in all that can be conveyed of naivety and pleasure in an island never truly invested.

His photography reaches beyond the horizon to focus on the ridiculous and the minuscule. It holds on to objects, the commonplace, which nonetheless, end to end, make sense and give an idea of geography. Yet the whole is built on autonomous images and the words of Patrick Rémy, the book’s editor. The book’s composition supports the singularity of each photograph. Arranged in a haphazard constellation and playing with small formats and almost full-page spreads, it recalls Wolfgang Tillmans’ hangings. These require the viewer to question each image for its own sake. Jonathan Llense follows the same principle.

Tahiti is a book stripped of stereotypes, approaching the island from the ground, from its multitude of human constructions. In contrast to the island’s tourist imagery, his photography creates neither meaning nor fiction. Instead, it elicits the ordinary as well as the artificial. “I’m attracted by the incongruous, the inexact, the wobbly”, the artist points out in the interview at the end of the book. The work forms a side-step conceived as a stroll, a simple “point of view” where humor and a taste for facetiousness can be discerned.

Jonathan LLense – Tahiti

Éditions Louis Vuitton, “Fashion Eye” collection

2023, 104 pages, 20.8 x 14 cm

Edited by Patrick Rémy & Anthony Vessot

Publishing director: Axelle Thomas

Graphic design: Lords of Design

Available in bookshops and online