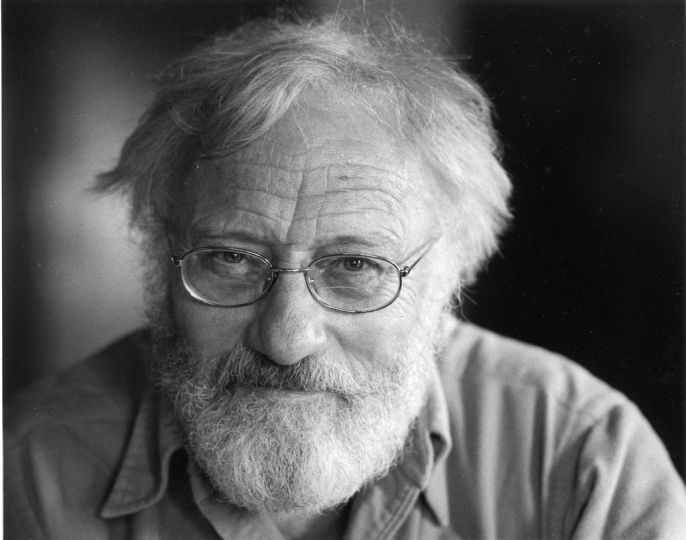

In February of 1958, then-journeyman news photographer Denis Brihat traveled with his friend Jean-Paul Clébert to the village of Bonnieux in a remote area of southern France. Sun-baked, picturesque villages nestled in the hills surrounding the Luberon Natural Park. The 30-year-old Brihat instantly fell in love with the land, which offered an escape from the “Parisian pavements” that had been his home and work space.

He returned to Paris and continued working on assignments with the Rapho photo Agency, but with ever diminishing conviction. An amusing incident with his friend Robert Doisneau, the romantically humanist photographer of Parisians, helped focus the absurdity of his continuing to live and work in the Parisian rat race. Doisneau had been hired to shoot the cover for a paperback murder mystery titled Sur Un Air De Trompette. A large American car had been borrowed. (One can’t help but think of the American gas hogs in the ’50s films of Jean-Pierre Melville.) Doisneau’s camera is aimed toward a partly open trunk from which protrudes the dangling hand of a corpse. The hand is Brihat’s. He emerges from the car trunk fully alive — much to the disappointment of an onlooking crowd.

Brihat met Solange seven years later, in July 1965, when she attended an exhibition of his work The Flora of the Luberon at the Gallery Les Contards in Lacoste. They married two years later and still live in the stone house that Brihat built as their home and studio. The gardens and surrounding land have been the subject of Brihat’s work for over half a century.

Brihat became interested in photography in his youth, when his father gave him a Vest Pocket Kodak in 1943. Shortly after World War II, 19-year-old Brihat, who had already dropped out of school several times, enrolled at the Paris school of photography in the Rue de Vaugirard. He left after three months. Some time later, he saw a revelatory exhibition of Edward Weston’s luminous 8″ x 10″ contact prints at the Galerie Vendôme; its influence would soon permeate his own artistic direction.

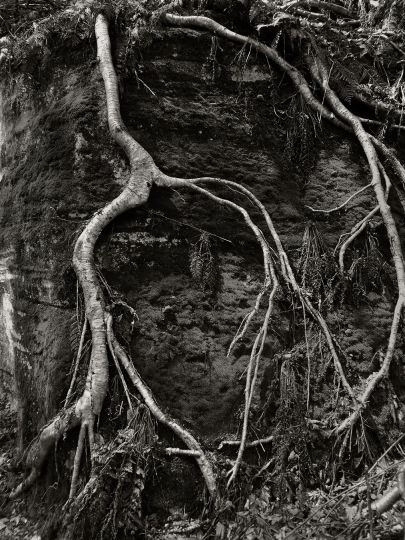

In 1950, Brihat had his first exhibition, which featured images of tree stumps. It was a harbinger of the photographs of grasses, reeds, trees and flora that he would devote himself to within a few years. (Also in the exhibition were photographs by future filmmaker Agnès Varda.)

Through Doisneau, Brihat secured an introduction to the director of the Rapho Agency, Raymond Grosset. Brihat became the agency’s correspondent in Provence. After a brush with writer and filmmaker Marcel Pagnol that went nowhere, Brihat met an “intellectual voyager,” Louis Frédéric, who invited him on what was to be a two-year stay in India to photograph the people and land.

The two men eventually parted amicably, and Brihat stayed a year longer, documenting people and customs in the north and absorbing tenets of the Sikh religion, which would profoundly influence his near metaphysical approach to photographing (at macro or micro levels) the flora of Provence and the Luberon Valley for the rest of his life.

A year after returning to France, Grosset entered some of Brihat’s India photographs into a new competition, the Prix Nièpce, which had previously been won by Doisneau and Jean Dieuzaide. (The latter became a lifelong friend and neighbor in Bonnieux.) Brihat won the competition. After a few abortive starts in Paris fashion photography and the symbolic corpse-in-the-trunk photo shoot, Brihat determined that he would spend the rest of his life photographing nature.

He settled in a shack without running water or electricity on a desolate area of the Claparèdes plateau. He had a battery-operated record player on which he played recordings of his beloved Bach. He eventually made friends and was able to build a studio darkroom. Then he met Bernard Coutaz, who had started the classical record company Harmonia Mundi. Coutaz used some of Brihat’s photographs of wild grasses and plants as album cover art.

In a 1975 exhibition of Brihat’s work at the Centre Culturel in Toulouse, fellow photographer Dieuzaide described Brihat this way: he had fled Paris and had come to live in this scrubland where every stone is a sculpture, every leaf a perfume, and every light a universe that distinguishes it from the Luberon. Bare-chested, smoking a pipe, he built his darkroom among the Holm oaks. And in this magnificent landscape, better than the best-equipped studio in Paris, he tirelessly developed theories about the future of photography.

It can be argued that “the future of photography” moved in a much more commercial and chaotic direction, but it can also be argued that Brihat’s quietly meditative work is, like Weston’s or Frederick Sommer’s, outside time (certainly ephemeral time) yet also deeply embedded in the slow pageant of the natural world.

Brihat did not become a recluse — nor is he now, at age 88. He shows his work around the world, and though he is not widely known in the United States (despite having a show at MoMA as early as 1967), he is revered in France, where many young photographers and critics make the pilgrimage to the Luberon to pay homage. He gave up teaching in 1988 to devote himself exclusively to his very time-consuming work; his printmaking techniques of color toning are every bit as demanding as the Carbro prints of Paul Outerbridge.

In 1969, Brihat, along with photographers Jean-Paul Sudre, Jean Dieuzaide and Jean-Claude Lemagny, started a summer photography festival in Bonnieux with the intention of producing it annually. The next year, Lucien Clergue began the Recontres Photographiques in Arles. The Bonnieux clan quickly came on board when it became clear that the very successful Clergue had the clout to make the Arles event a “must do” annual affair; it has since become the most important convocation of world photography. Brihat signed on for many years as a teacher and supporter. A Wikipedia page lists the artists who have participated in the event over the course of its history.

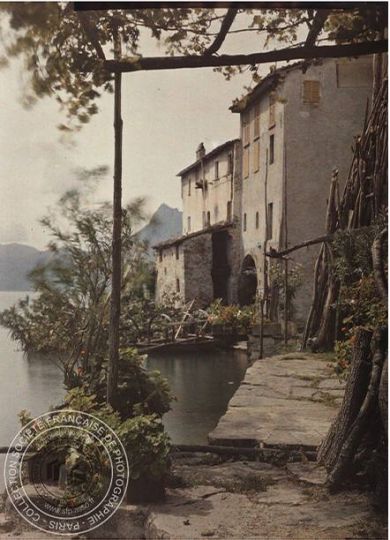

When Brihat worked on assignment for the Rapho Agency, much of his work was on Kodachrome. Aesthetically, he abjured color, and his first landscapes and botanical studies in the Luberon were in black-and-white. Many were larger than the standard 8” x 10”. When Solange first saw this Brihat print of grasses in 1965, it was over 6 1/2′ tall.

From the beginning of his work in the south of France, Brihat intended his works to be framed and displayed like paintings. This was not a matter of pretention or vanity, but simply a technique that enabled the viewer to closely engage with his delicate subjects.

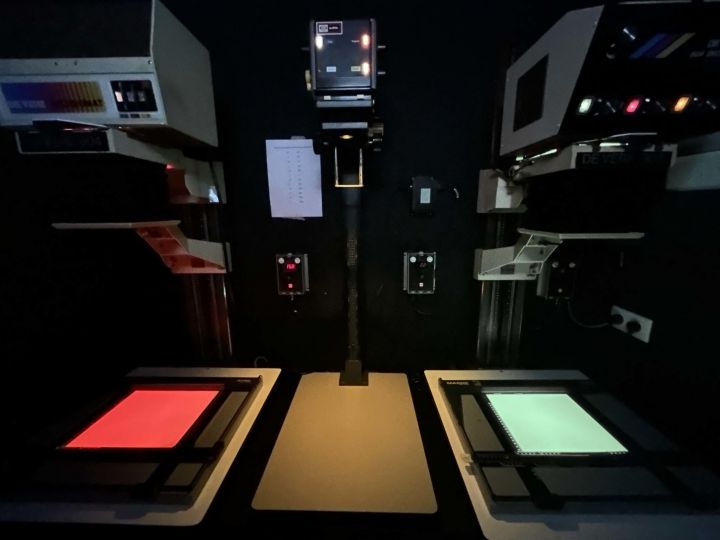

Didier Brousse, director of the Camera Obscura gallery in Paris (which represents Brihat’s work in Europe), explains Brihat’s evolution into color — which did not happen via conventional color printing, but through a complicated process of toning the salts of his black-and-white gelatin silver photographs print by print, replacing them with other metal salts that employed a restrained color range and: … [Also] had the mysterious depth of enamels. The hues he obtained weren’t just beautiful, but also permanent, by contrast with the chronic instability of silver-based color photography. Each print required several dozen operations … Derived from the chemistry of the printing process, they were controllable with certain limits. Some of the reds obtained by sulphuration and gold chloride toning had an intensity and presence.

Photographer Alexey Titarenko has visited Brihat in the Luberon. Titarenko, a poetic photographer of urban life, also creates marvelously delicately toned prints. He sent me this note about Brihat’s methods: The white background is most probably strong bleaching using brush and fixer … The sepia has two parts: first bleaching that he may do also using brushes, and then, after washing, a toning solution which is either sodium sulfide (Na2S) or thiourea with sodium. After washing, you apply a gold chloride toner; everything that was sepia becomes red (like the American flag on my 58th Street print).

I‘ve not discovered a more detailed analysis of Brihat’s process. By contrast, Outerbridge’s Carbro process is detailed step by step in his 1940 book, Photographing in Color. There is, however, such consistency to Brihat’s process that Brousse (as an observant dealer) insists that it is not possible to distinguish between a color print made from 1977 and one made a few years ago. From the very beginning, Brihat has tightly controlled the print editions of his work, with many images restricted to as few as three prints, and none made in more than a dozen.

Finally, why onions? Brihat has done hundreds of studies of poppies, grasses, lichens, trees, cabbages and kiwis. It’s pure speculation on my part, of course, and I doubt that Brihat would disclose too much about the particular place the humble onion has in his “oeuvre,” though he does go on about them in the video for several minutes (starting at 7:30). He asks rhetorically whether it’s okay to be obsessed with a single object. After all, Cezanne painted Mont St. Victoire over and over. I’ve been fascinated by Pierre Bonnard’s practice of painting his wife at the same age over and over, even years after she died.

In the essays featured in the new book of Brihat’s work, there is much text that I find inscrutable, French linguistic folderol and tongue-twisting verbal axioms. One of the more readable is by critic Michel Tournier: “When Brihat enlarges a slice of lemon to the size of a cathedral rose window, when he puts a single acacia seed or spike of lavender on a neutral background — a background of nothingness — he raises these tiny harbingers to the power of the cosmos, and infinity is certainly what he intends to possess, infinity withdrawn from the wear of time, an eternal infinity.” This observation reads rather “grand” in its ambition, but, yes, there is an almost heroic quality to Brihat’s still lifes when you view the prints in person. I saw many of them several months ago at the Nailya Alexander Gallery.

What distinguishes Brihat’s studies from Weston’s is not the level of craftsmanship of the print — they are comparable — but the sense of “aliveness” in Brihat’s work. You can almost feel his subjects pulsating as they “pose,” whereas Weston’s still lives of vegetables or fruit appear lifeless, justifying the French expression natures mortes. As variable as the grasses, lichens, pears, kiwis, cabbages, tulips and ranuncului are, there is something I find alluringly unique about Brihat’s onions.

The onion we eat is only a small part of its being: the root, the only part we tend to see in our deracinated experience of sorting through onions in the supermarket bins. What Brihat photographs is the whole onion, pulled from the soil with root tendrils and dirt still attached, and onions that are left to dry as new growth breaks through the bulb, reminding us that even in its drying state, it is vibrantly alive. The pattern of an onion’s post-harvest growth is relentless in its green second life. When Brihat decides to focus on the sloughed-off onionskin that we casually peel off and toss aside, he captures the skin’s transparent beauty, a delicate exercise in the full range of monochromatic toning.

I confess that I had not heard of Brihat’s photographs until a few years ago, when Nailya Alexander introduced them to me. The images were a stretch for me, as so much of my focus on the history of photography has been on family-of-man themes and the life-and-death records of conflict photographers in the world’s hot spots. I ask myself whether I am seeking surcease in these quiet images from the mad violence around us. Bombarded daily by new levels of intolerance and horror, does the life in art and the subject matter chosen by Brihat, even in his youth, tug at my conscience?

As fine as anything I’ve yet read about the emotional density of Brihat’s images is this quote from an exhibition catalog: “The resulting prints are sumptuous, of remarkable richness, refinement and beauty. The artist is considered a master without equal of these rare printing techniques. But, for Brihat, the sole importance of this superb craft is to express his contemplative poetic vision and profound emotional connection to the natural world. The Zen-like purity of focus, sense of delicacy and the sublime, resonates throughout the work and harkens to the heart and the contemplative mind.”

Is it possible that photographs of such humble natural objects can, in fact, lead us into a state of near metaphysical contemplation?

John Bailey