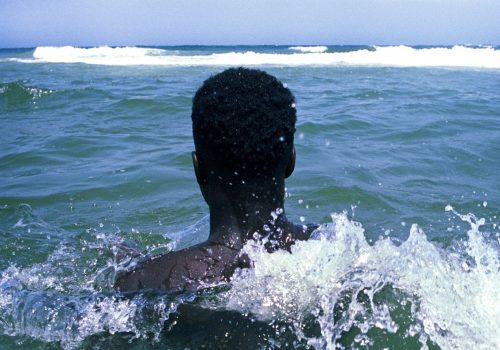

The W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund has announced on October 18, 2017 that Daniel Castro Garcia is the recipient of the 2017 Grant in Humanistic Photography for his project, Foreigner: I Peri N’Tera — a Sicilian colloquialism that translates as “feet on the ground.”

Selected from a talented group of 12 finalists, Foreigner is the second chapter of Garcia’s ongoing project on the migrant/refugee crisis in Europe, focusing on Sicily, Italy and capturing the lives of those who survived the long journey across the Sahara Desert and Mediterranean Sea.

The project takes a hard look at unemployment, exploitative labor, and the difficult process of receiving documentation in a new land. The Smith Grant now allows the photographer to continue his project with subsequent chapters set to explore the psychological impact of these journeys and the struggles of integrating into new communities throughout Europe.

The annual grant, which was increased to $35,000 by its board of directors this year, was presented to Daniel Castro Garcia during the organization’s 38th annual awards ceremony at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) Theater in New York City this Wednesday evening.

“The jury was struck by Mr. Garcia’s humanism which is appropriate for a grant that honors the legacy of W. Eugene Smith,” explained W.M. Hunt, longtime Smith Fund board member and the Chair of this year’s adjudication committee. “The pleasure of judging the Smith Fund is the strength and range of the work submitted. The judges were aware that having 12 finalists would be a bit unwieldy, but they wanted to ask questions and consider each of the proposals for a longer time,” Mr. Hunt continued. “They are delighted with the selection of Daniel Castro Garcia as the $35,000 Smith Grant Recipient and felt his work was blessed with clarity and wonder.”

The Eye of Photography also spoke with London-based photographer Daniel Castro Garcia about his moving project.

Foreigner : I Peri N’Tera, is the second chapter of your ongoing project on migrant crisis in Europe. Would you mind reminding us how the first chapter, Migration into Europe 2015-2016, was different?

In many ways, Foreigner: I Peri N’Tera both continues and develops the approach set out by the first chapter of this project. It is driven by proximity, intimacy and a desire to look at individual people’s stories and maintain the idea that every person counts, is important, and has something valuable to contribute or say. Where Migration into Europe 2015 – 2016 offered a rather macro look at the wider European migrant/refugee crisis, this chapter takes a more precise look at the lives of young, unaccompanied minors that are living in reception centers in Sicily. Film, writing, graphic design, education… there are a lot of angles being explored in this new work.

I am emotionally involved with the people I am working with and I am concerned about their futures. These are young and extremely vulnerable people that have been victims of human trafficking, physical, mental and sexual abuse, racism, and prostitution. Every single boy or girl that I have met has been deeply affected or traumatized by his or her experience. It is an extremely complicated situation here that requires deep thought. After all, these young boys and girls are here in Europe to stay, they crave a prosperous future like anyone else yet the obstacles they face are huge. Ignoring them will lead to a generation of people being crippled by trauma and segregation, which is simply unacceptable.

Why did you choose to document this subject in Sicily?

In 2015 when this project started I was preoccupied by the extreme and alarming coverage of migrant vessels that were leaving Libya. I had been noticing the images of over-crowded boats for several years but in 2015 the story was becoming front-page news and the repetitive nature of the images coupled with the tone of the vocabulary being used was becoming increasingly worrying. The story was dominated by statistics and political rhetoric and little more.

Lampedusa, (part of the Sicilian province of Agrigento), was a pivotal step for the project. Not only had the visual documentation of the situation started, but also it did so without any people to photograph. The Italian government had transferred everyone to Sicily or Southern Italy, and new rescue missions were being redirected to Sicily. This meant that I was faced with the aftermath of the movement of people and an opportunity to take a slightly more forensic look at the reality of these journeys. The boat graveyards and cemetery afforded the work a very sober tone and a seemingly spiritual responsibility. Since that trip this project has always and will always be dedicated to the memory of those that passed away making the journey to Europe. They are the people that no one cares or thinks about and are quickly forgotten and rarely is anyone held responsible.

Mainland Sicily was a very different experience. It was here that I started to make friends with people and learn about their lives in Italy. I also started to discover a huge number of people sleeping in the streets in shocking conditions surrounded by feaces, rats and rubbish.

Overall, I felt that the individuals in this region were being grossly misrepresented and unheard and as member of European society, I found this worrying and incorrect. Since that first trip I revisited Sicily and the people I had met there several times, and each visit opened new doors for the project. Sicily is a remarkable island with huge contrasts and I hope this work will contribute valuable information on the situation there.

What does I Peri N’Tera mean as a title and to you?

I Peri N’Tera is a Sicilian colloquial phrase that literally means “feet on the ground”. It is used in conversation to ensure that someone does not get carried away with his or her ambitions and dreams. From the moment I heard it I knew that it was the title for this body of work. The literal and metaphorical meaning of the phrase is again, sobering and thought provoking.

Personally it means a great deal. Having spent the last three years around people that have dreams and ambitions for their lives, there is a very real bureaucratic and social dynamic at work here that means achieving them will be unbelievably difficult.

What do we learn in your photographs? What are the issues pointed out?

Aside from highlighting and contributing to the body of information about the migrant/refugee crisis, the work looks at a range of issues in different areas. My work with Aly Gadiaga for example considers the issues important in his life; the slow passing of time and the difficult wait for documentation. My work with Madia Souare also opened the project up to consider the impact of trauma. This is a theme I am concentrating on now more than ever. I feel a great level of responsibility with every day that passes over here. Some of the children are more damaged than others and they have no method to process their experiences. One day I found one of the boys sitting in a dark corridor with his head in his hands rocking back and forth. “I’m not feeling good. My head hurts. I am thinking too much.” His pain is real. It is immense.

Often, whilst talking, the boys zone out and stare into space for minutes on end without blinking. They have told me stories of being dumped in the desert for days with no food or water, how in Libya they witnessed dozens of people being shot and killed. One boy was stranded in the Mediterranean for 3 days and then picked up by Libyan authorities and taken back to land. All of these experiences are vital for the new community to understand.

Finally, all I can really hope is that our work serves as a historical documentation of a very disappointing time in European history. That the images of people marching through fields in 0 degrees and the elderly or disabled sleeping in fields really makes a strong point of the twisted political culture that governs our societies and allowed for these scenes to take place. It is vital that something is learnt from this.

What can you tell about the migrants you met and photographed?

I feel that I have been very lucky to meet people all along this journey that have been kind, gentle and open. In Calais, Austria, Slovenia, Idomeni etc. everywhere I went I was offered a seat at the table and afforded the opportunity to break bread and share an experience. I understood very quickly that despite their experiences, fundamentally we were exactly the same. Similar hopes and ambitions. Similar habits and beliefs.

What did you and do you feel regarding them?

Ultimately I feel a great deal of responsibility to do the right thing with our work. I grew up in the UK with people from all kinds of backgrounds, races, religions etc. and I, like all of my friends, was taught that I was part of a society that promoted tolerance, respect and understanding. There is nothing naïve or unrealistic about this, it is a good thing. There are obvious aspects of society where poverty, institutional racism or lack of education results in a less tolerant view of the world, but that will always be true.

With that in mind I feel the same about the people I meet during this work as I do about anyone else. I feel that to solely think about the people I am meeting, as migrants or refugees, is narrow-minded. I am not just a photographer the same way a refugee is not just a refugee. I feel sorry that so many people have their lives on hold in Europe and I feel sorry that such a tremendous growth in right wing, ultra-conservative, nationalistic politics has risen so greatly. The media and politicians are greatly responsible for this. So many lies have been fed to the public and even when the statements have been discredited, the damage has already been done.

No part of my work petitions for open borders or anything of the sort, but, as the son of migrants myself, who fled a very poor and underdeveloped Spain in the late 60’s, I feel an obligation to make the point that people have something to offer and can contribute positively to society if they are given the chance.

Your photographs are mostly staged and intense. What can you tell about your style?

I think my style has always been the same. When I first fell in love with photography and found photographers that moved me I recognized a thread in their practice that inspired me. Alberto Garcia-Alix, Nan Goldin, Tim Hethertington… their work represented a level of engagement that stimulated me and I was interested by their interaction not only with their subjects but also the role of photography itself. There is such a poetic tone and value in their work and I love that photography can possess this quality. I believe that portraiture serves as both a confrontation and a mirror. You can learn something about another person, but also a great deal about yourself, both as a photographer and member of the audience.

Why is it important to document the refugee crisis?

I believe it is important because ignorance and fear mongering have so quickly governed the narrative. It has also been reported in a way that has sought to either sanctify or vilify the people in question and this is not correct either. For me the project is about creating balance and a well-rounded debate and a platform for people to have some input and consideration about the way they are depicted. In the case of Aly and Madia, we have made films together and they have provided written contributions that have been presented alongside the words and work of people like Alexander Betts and Lindsey Hilsum, both leaders in their respective fields. We feel proud of this, because we have not underestimated the intellectual potential of those that have experienced this crisis first hand and we have enabled them to speak without censorship or any hidden agenda.

How do you think your photographs are making a difference?

It’s impossible to say. I believe they are making a positive difference to the lives of my collaborators because it proves that someone cares about how they think and feel. In addition, I think there is an engaged audience for the work because the project has been published and written about internationally across a spectrum of magazines and websites as well as being exhibited internationally. For us that has been particularly exciting as it has allowed for a reinterpretation of the work to occur and new questions and answers have come from this.

What can the viewers of your pictures do in order to help the people portrayed?

Be active citizens. Whatever the viewer’s opinion is, either conservative or liberal, left or right etc. I hope that they take the opportunity to think harder about their society and social values. At a time in which inequality is greater than ever, it will only change when people become active and conscious and decide to put fear aside and focus on the positives. As far as charity work goes, I know there are many wonderful charities out there such as Help Refugees UK and ProActiva Open Arms that have done extraordinary work and they started out at grass-roots level and have expanded their operations and made extraordinary contributions to vulnerable people’s lives. This has all been achieved through like-minded people coming together and addressing very clear injustices.

You received the BJP International Photography Award 2017 last year. How is the W. Eugene Smith Grant going to help you?

Massively. It’s difficult to put into words what a lifeline this has provided the project. I am now based full time here in Sicily and so my hope is to follow the children from adolescence into adulthood and follow their stories for as long as I can. I’m interested in what young people have to say. After all they are the future of Europe. I am also hoping to visit their countries of origin and meet their families. I want to take a closer look at the situation in Africa and learn more about their lives and what they have left behind.

Ultimately I want this project to open up to other contributors where possible and bring in experts to add their knowledge. In our last publication, Foreigner: Collected Writings 2017, we were so lucky to have the involvement of Alexander Betts, Lindsey Hilsum and Forensic Architecture. It is practically impossible to argue with their findings and a wider audience needs to see what they are doing. If we can share platforms and be open about our work, then I hope we can achieve some really positive results. The situation and the people involved deserve it.

Interview by Jonas Cuénin

The images in this portfolio were possible with the support of the Magnum Foundation Fund.

Instagram: @foreignerdigital