Her name is Anna Voitenko, she is 30 years old, her dream was to attend the Festival “Visa pour l’Image.” Apparently, the French authorities refused to grant her a visa. It is her agency (The Desk), which has given us her pictures. Anna Voitenko worked for two years on his village Iza (Romania).

Michel Philippot

These are images and her text:

“The old and large village Iza is located in a wide plain among Carpathian ridges. It is well-known because all its residents, the local priest and policeman included, are engaged in withe wickerwork. Instead of carrots, cabbages, and potatoes, they grow willows on their plots of land. For the whole year, they carefully look after the plant, earthing it up, and keeping it wet (which makes withe firmer, whiter, and more flexible). Then in the spring, during the Orthodox holiday of Holy Protection, they go and cut the harvest it down to the last twig. The entire village, from kids to elders, goes out for withe cutting. Even 80-year olds do not stay at home working equally with the others.

Incidentally, they say that withe is considered to be an “energy-giving” plant which increases the body’s natural defenses and prolongs life. And the villagers live long here, as the contact with this enhances their health and energy. During the harvest, the field is a total mess full of horses, tractors, trucks and cars loaded to the brim with two-meter twigs and swimming in the spring mud. One can hear the bellowing of chainsaws and the clicking of shears. The willow bush is thinning out. Then they boil the twigs in huge cauldrons adding the holy water there.

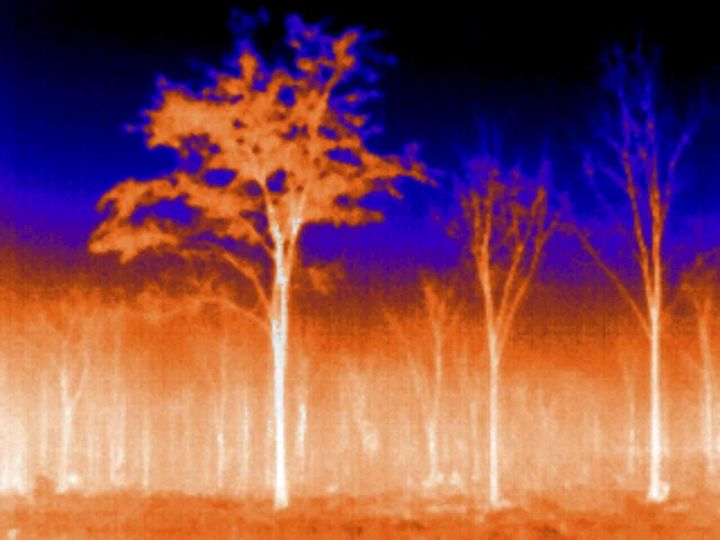

Smoke is ingangs over the village like fog. Old car tires found around are used as free fuel, and everyone’s face is smudgy, except for the shining eyes. Withe has to be boiled to ease debarking and make the twigs more resistant and flexible. After, they are also painted so that the wonderful wickerwork would please to the eye and attract one with its ornament. People inhabited the village territory since prehistoric times and, according to a legend, they did withe wickerwork exclusively. Because the occupation is one of the oldest human crafts being even older than pottery and the only one still existing in its primordial form. Our shaggy ancestors who lived caves and wore animal skins did wickerwork in the same way as Maria, a basket maker from Iza. Even weavers learned thread-weaving from wicker workers. The Iza villagers are aware of this, and they are very proud of their uniqueness. You cannot any other village like this in the whole Europe. It is the only one. Yes, the do wickerwork in many places but not by the entire village…Here, a number of things are made: furniture, tableware (bread and fruit containers) of different shapes, vine bottle pouches, although especially beautiful are the Iza baskets. In Orthodox Christianity, it is customary to use baskets to bring food to the church for consecration during Easter (the holiday of Christ’s birthday). Such baskets are often called the ritual ones. They must be especially well-decorated differing from others by exquisite weaving, patterns, and coloring. The Iza masters are especially good at making exactly these baskets, and the Easter baskets from Iza are a wonder. They are started to be made in February, after Epiphany, when streets are cold and frosty. There is a belief in Iza: if one is the first to make the Easter basket at the beginning of the year, then they year will be lucky in everything for the person. It is forbidden for the villagers to curse, dance, or sing during the work on such baskets. Until, Easter, they even speak very softly to each other. Using consecrated twigs, they weave mysterious talismanic patterns. It is believed that, if one consecrates the Easter cake in a basket with such patterns, one will steer clear of trouble for the entire year.

“We make baskets of all kinds – the round, square, and oval ones decorated with wreaths as well as densely-woven and tracery ones”, says the master Maria Shumikha – “For the ritual baskets, we choose the best rods harvested to the accompaniment of special prayers.

“We begin to weave the basket from the bottom, – she continues, – inserting decorations in the walls, the simplest of which features crosses. There are also much more complicated patterns but they are kept secret by every family of masters and transferred from generation to generation. Some masters can steal others’ secrets and use them in their craftwork but it only strengthens the competition and betters our art. Masters, be it women and men, the young and the old, always seek new things working for twelve hours a day. Their hands are strong and sinewy, and the veins under their skin resemble the twigs of with woven in an incredible talismanic pattern. This is Carpathians’ fame and power.”

Anna Voitenko / Agence Le Desk