Excerpts from the “All my books”: Paul Strand’s Arc

VASA Journal on Images and Culture, Theme essay on “Thoughts on photography”, Bruce Jackson theme editor.

Bruce Jackson, an American photographer, film maker and noted essayist is editing a theme titled “Thoughts on Photography” for VJIC. What follows are a number of his comments on the work of Paul Strand an American photographer.

The full thematic series my be accessed here.

In his essay Jackson notes that “Strand, the greatest of the modernist photographers, was born in New York City in1890; he died in Orgeval, France, in 1976. His work had profound influence on, among others, Georgia O’Keeffe, Walker Evans, Ansel Adams (who thought he might become a piano player until he met Strand), and Edward Hopper. Strand, Alfred Steiglitz and Edward Weston were the three photographers most responsible for getting photography accepted as an art form in the United States.

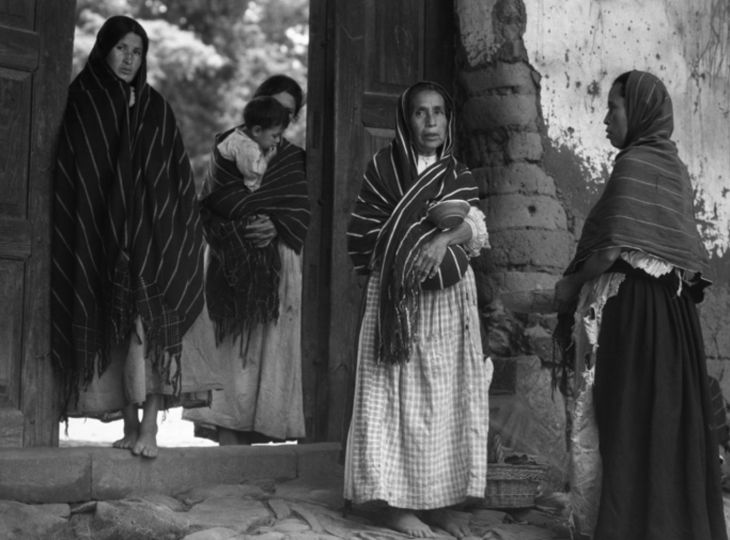

During a two-year stint in Mexico (1933 and 1934), Strand’s aesthetic vision and sense of mission made a critical pivot. It would take him several years to know what to do with it.

He is best known for some of his single images: “Wall Street” (1915) “White Fence” (1916), “Blind Woman” (1916), and “A Family” (1953). They are great images. But they’re not what he, finally, thought his work was really about.

… In 1915, Strand said, “I really became a photographer. I had been photographing seriously for eight years, and suddenly there came that strange leap into greater knowledge and sureness. I brought a group of my things in to show Stieglitz, and when I opened up my portfolio, he was very surprised. I remember he called to Edward Steichen, who was in the back room at ‘291,’ and had him come out and look, too. Stieglitz said, ‘I’d like to show these.’ He also told me that from then on I should think of ‘291’ as my home, and come there whenever I wanted. It was like having the world handed to you on a platter. It was a very great day for me, matching, in a sense, the day that Hine took us to Photo-Secession and I saw the work of those other photographers for the first time.

(Strand) never questioned the morality of it. I always felt that my relationship to photography and people was serious, and that I was attempting to give something to the world and not exploit anyone in the process. I wasn’t making picture postcards to sell.

… You see, I don’t have any aesthetic objective. I have asesthetic means at my disposal, which are necessary for me to be able to say what I want to say about the things I see. And the thing I see is outside of myself—always.”

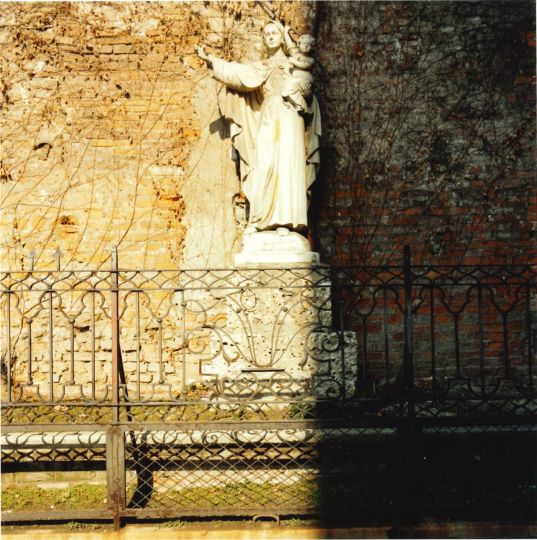

Bruce Jackson wrote further, Stand “… became a realist, not an aesthete or documentarian. He wanted to capture what he thought the essence, the reality, of the people and places he photographed. He was as willing to manipulate the facts of the moment as he was to tinker with his negatives in prints: he put a hat on a girl in Italy was not hers; he posed a man in the Hebrides against a wall that was not his wall. But the photo was that girl, in that place, and that man, in that place, and they all were Strand’s sense of what the life and place were really about.”